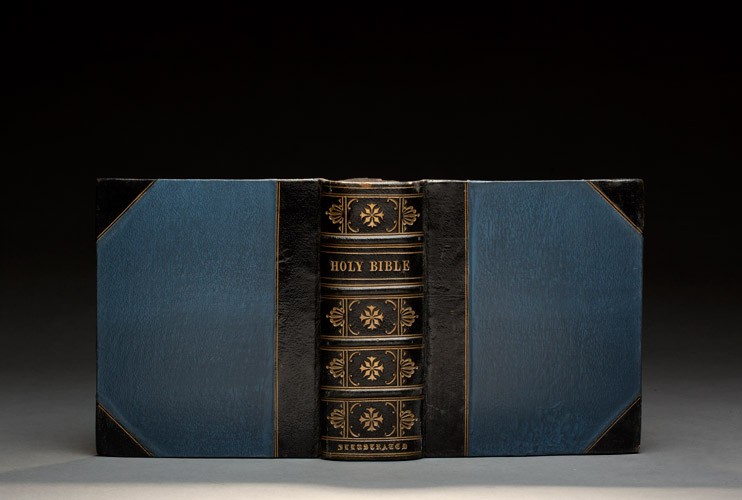

(RNS) — In 2015, Montreal-based artist Guy Laramée placed a large-format Bible from the 19th century upright with the spine open. Then, using a power grinder, he carved a landscape into the pages and painted along the curvatures, evoking the space of a cave whittled into a sheer mountainside.

It is a beautiful summoning of desert spaces, conjuring the place of the biblical prophets. It is, however, an unusual treatment of the Good Book.

And it is one that would never find its way to the $500 million Museum of the Bible, opening Friday (Nov. 17) in Washington, D.C. That museum is dedicated to the preservation and presentation of the sacred text through the ages.

Guy Laramée, “The Holy Bible (The Arid Road to Freedom).” 2015. Photo by Alain Lefort. Courtesy of JHB Gallery, New YorkLaramée, along with a number of contemporary artists, has been working with books not as muse, but as medium. You could call these artists book lovers, but only in the way that you could call Michelangelo a marble lover or Edward Scissorhands a tree lover.

Guy Laramée, “The Holy Bible (The Arid Road to Freedom).” 2015. Photo by Alain Lefort. Courtesy of JHB Gallery, New YorkLaramée, along with a number of contemporary artists, has been working with books not as muse, but as medium. You could call these artists book lovers, but only in the way that you could call Michelangelo a marble lover or Edward Scissorhands a tree lover.

The trade-offs involved in this sort of love become much more stark when the book in question is someone’s version of sacred scripture.

Artists such as Carole Kunstadt, Islam Aly and Jan Owen create their own sacred books, stitching together pages of handmade papers in creative ways, writing their own poems and prayers or carving symbolic designs out of the pages. The finished product is like a book yet also like a piece of sculpture. It’s not clear if the works belong in the library or the gallery.

Other artists, such as Laramée, Brian Dettmer and Meg Hitchcock, do the opposite. They each work in books the way other artists work in oil or marble, cutting away unnecessary elements in order to make way for a final product. Some of the most striking are those that utilize religious texts such as the Bible, Quran and Torah.

Guy Laramée, “The Holy Bible (The Arid Road to Freedom).” 2015. Photo by Alain Lefort. Courtesy of JHB Gallery, New YorkHitchcock’s recent solo show, “10,000 Mantras” (on view at the Studio 10 Gallery in Brooklyn, Sept. 8-Oct. 8), displayed some of the creative uses of Holy Writ that probably never occurred to religious adherents.

Guy Laramée, “The Holy Bible (The Arid Road to Freedom).” 2015. Photo by Alain Lefort. Courtesy of JHB Gallery, New YorkHitchcock’s recent solo show, “10,000 Mantras” (on view at the Studio 10 Gallery in Brooklyn, Sept. 8-Oct. 8), displayed some of the creative uses of Holy Writ that probably never occurred to religious adherents.

Her artistic process has been to take sacred texts, carefully cut out individual characters from them, and then paste those characters in another place to form new words and new sentences that comprise other sacred texts. A Bible, in one example from the show, is cut up and the letters are turned into the Buddhist mantra, “om mani padme hum,” repeated 10,000 times. In this way, one text is transposed into another.

Asked whether he and artists like him are engaged in the desecration of sacred books, Laramée countered, “I’m sacrificing them, and like in any true sacrifice, the victim becomes sacred precisely because it is killed.”

For her part, Hitchcock comes from a strict evangelical Christian upbringing, and so knows what it is to have a high regard for the Bible. As she moved away from the faith of her youth, she retained a respect for sacred texts. She cuts them into pieces painstakingly, letter by letter — two short vertical cuts, two short horizontal cuts, repeated thousands of times. In this activity, Hitchcock finds, “I can get into a flow, and it’s very meditative.”

A detail from Meg Hitchcock’s “Throne: The Book of Revelation.” 2012. Permission by Meg HitchcockIn earlier artworks such as “Throne: The Book of Revelation,” Hitchcock undertook a radical statement of the unity of faiths: She cut out individual characters from an English language translation of the Quran and then pasted them on a large sheet in a dynamic design, spelling out the entire Book of Revelation from the Christian Bible. At the center of that piece she created a mandala spelling out the “throne verse” from the Quran, with all the characters cut from a Bible. In a single work the Bible is transformed into a Quran, the Quran into a Bible.

A detail from Meg Hitchcock’s “Throne: The Book of Revelation.” 2012. Permission by Meg HitchcockIn earlier artworks such as “Throne: The Book of Revelation,” Hitchcock undertook a radical statement of the unity of faiths: She cut out individual characters from an English language translation of the Quran and then pasted them on a large sheet in a dynamic design, spelling out the entire Book of Revelation from the Christian Bible. At the center of that piece she created a mandala spelling out the “throne verse” from the Quran, with all the characters cut from a Bible. In a single work the Bible is transformed into a Quran, the Quran into a Bible.

“I search for the common threads that run through all scripture,” she said, “then weave them together to create a visual tapestry that speaks to our common ancestry, and ultimately, to our human condition.”

To be sure, others have not been so convinced of the reverent intentions behind the artistic liberties taken with sacred books.

In 2005, when London’s Tate Modern was about to display John Latham’s “God Is Great (#2)”— a sheet of glass slicing through a Bible, Quran and Talmud volume — the museum pulled the piece from display, fearing negative reactions.

And in 2014, in Frankfurt, Germany, three men entered the Portikus Gallery, agitated the workers and stole the Quran from the middle of Latham’s installation “God Is Great (#4)”, one of the last works by Latham, the father of what might be called the Scriptural Manipulation Movement, who died in 2006.

Hitchcock, whose artworks now sell well enough for her to work full time in her studio in upstate New York, says that every once in a while her gallery owner gets an earful from some visitor about the potential sacrilege going on. Even so, most people tell her how much they appreciate her art, and this, she says, is “even from some pretty hard-core believers.”

With the rise of the internet and smartphones, many doomsday essays have bemoaned the “death of the book” and the “end of reading.” And if fewer people are reading books, then even fewer are reading the holy writings of religious traditions.

So perhaps artworks of the recent trend can be seen as a nostalgic creation of monuments to objects whose power to express urgent and sometimes sacred ideas is fading. And perhaps this goes some way to explaining why the Museum of the Bible is opening now.

Hitchcock said her work could theoretically be “read,” but she also arranges the characters without punctuation or spacing, as she is “trying to discourage a literal reading.”

By downplaying the content of books — what they say — and emphasizing their form — their physical dimensions — these artists have found a medium that can be played with, sculpted, cut into pieces.

In contrast to Laramée’s power grinder, Brian Dettmer takes an X-Acto knife to the pages of books, carving through the leaves one by one to reveal layers of images and words throughout a book.

In a TED Talk in 2014, Dettmer said we could think of books as “living things,” and thus “they also have the potential to continue to grow, to become new things.” Through the act of destruction, a new creation is born.

Between destruction and creation, the physical nature of letters, pages and bindings takes on new lives, in new forms.

By paying attention not only to the spiritual nature of the words and sentences in the holy books, but also to the very form of the book, these artists reinvent the sacred texts in new ways. As Hitchcock noted, even Bibles subject to standard use do not remain physically pristine or unaltered. Their pages, she noted, “are stained with the tears and fingerprints of the devout.”

Through artworks such as hers, “words of God” truly become incarnate.

S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate is a writer, editor, public speaker and part-time professor at Hamilton College. Follow on Twitter: @splate1