(The Conversation) — QAnon’s cryptic predictions read like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel. In the science fiction author’s book, Valis, the protagonist experiences visions he interprets as revelations about alien intelligence, political scandal, and secret wisdom. The book was inspired by Dick’s own experiences and contains imagery drawn from early Christian gnostic groups — loosely organized religious and philosophical movements — that claimed to possess special knowledge about the true nature of the universe.

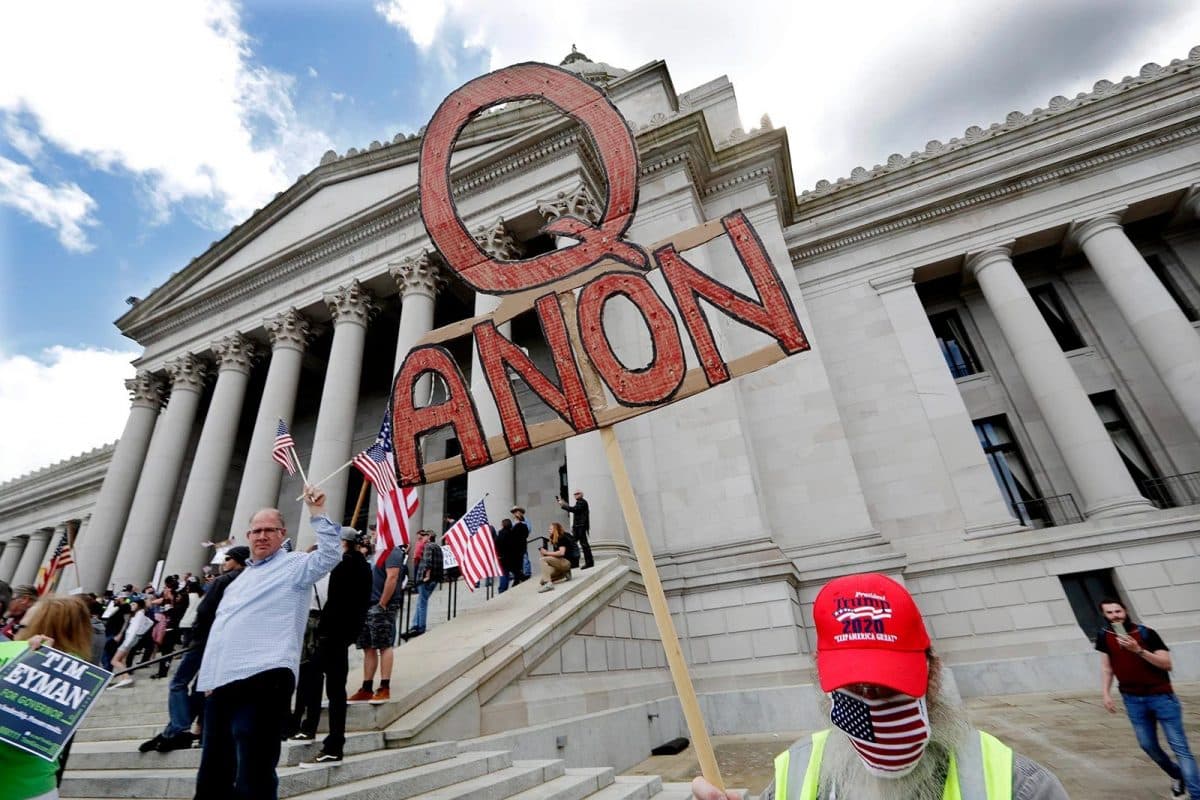

A demonstrator holds a QAnon sign as he walks at a protest opposing Washington state’s stay-at-home order to slow the coronavirus outbreak on April 19, 2020, in Olympia, Washington. (Elaine Thompson/Associated Press)

For the followers of QAnon, an equally gnostic vision of reality is unveiled through obscure remarks from their online oracle.

Although debated by modern scholars, the basic premise of the gnostic worldview is that reality is not what it appears. Ancient gnostics believed that the world we perceive is, in fact, a prison constructed by demonic powers to enslave the soul and that only a small spiritual elite are blessed with special knowledge — or gnosis — that enables them to unmask this deception.

A revisionist reading of reality, in which social and political events are only understood by a chosen few, is the basis of the QAnon gospel. Yet, it is also a worldview driven by long-standing religious impulses clearly evident to historians of early Christianity.

QAnon Followers Today

QAnon followers — predominately Donald Trump supporters and conservative Christians — appear to believe that the real cause of this past year’s crisis was an underground religious war being waged by U.S. soldiers against legions of Illuminati demons.

They believe that these beings torture and abuse children in order to procure a highly-addictive drug called adrenochrome used by liberal and Hollywood elites. Building on the Pizzagate conspiracy theory of 2016, this belief has now morphed into a more expansive “end of the world” narrative.

Much of it reads like science fiction.

The QAnon story casts Trump as a kind of radical Christian ruler, deputized by God to wage war against the liberal infidels destroying a once great and holy nation. Followers believe that the former president’s tweets were not chaotic ramblings, but in fact the words of a Christian oracle, the meaning of which only true believers can decipher through online message boards.

QAnon is a curious mixture of sex scandal, anti-government protest, science fiction, biblical religion, and military ethos. These ingredients make for a uniquely American religion and manifest the “cult” of Trump in its most extreme form. All of this seems incredible, even amusing, except for that fact that QAnon is tearing apart families and poisoning American politics.

A Look at History

Although very much a product of the current cultural environment, QAnon also reproduces trends and dynamics from the earliest history of Christianity. In particular, the first Christians also viewed their world as a cosmic battleground and struggled to interpret an often violent and chaotic social context. Like QAnon today, some early Christians speculated about overturning their contemporary socio-political order using imagery of demons and holy war.

For example, we might look to the Apocalypse of John, the final book of the New Testament and the first surviving early Christian “apocalyptic” text. Biblical scholars have long understood that this work is an encoded, first century C.E. attack against Roman imperial power, yet, John’s apocalypse has often been interpreted as a scriptural key to how the world will end.

The earliest Christian readers of the New Testament thought that the end of times was imminent and, ever since, Christian groups have periodically arisen to proclaim that the hour is at hand, only to be disappointed.

Usually, such millenarian sects appear in times of crisis and instability, and are often unpredictable. Millenarianism is a recurring belief in religious, social, or political groups about the coming fundamental transformation of society, after which “all things will be changed.” In fact, the Apocalypse of John was not widely accepted into the emerging New Testament until well into the fourth century C.E. Many early Christian leaders thought the text encouraged extremist sectarian impulses that the institutional church found difficult to control.

Inevitable Immolation

QAnon is not so much a “church” (in a sociological sense) but a loosely connected network of online commentators. Even though it was birthed in a matrix of evangelical fundamentalism and Republican extremism, QAnonners are under no recognizable institutional framework.

They themselves might assert that their so-called “White Hats” represent an organized military force carrying out complex operations in an underground war. It is important to recognize that QAnon is more than just a “conspiracy theory” or fringe political movement: it has all the hallmarks of a new religious movement, one that manifests deeply rooted tendencies in sectarian Christianities from the past.

Few religious sects successfully transition to stabilized religions. Most burn themselves out. Unfortunately, the nearly inevitable immolation that occurs often consumes more than just the believers themselves.![]()

Timothy Pettipiece is an assistant professor at Carleton University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.