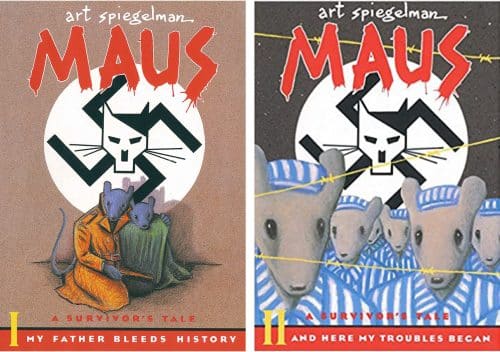

Over the weekend, a 30-year-old graphic novel skyrocketed to the top of Amazon’s bestseller lists. On Monday, Maus took the number 3 spot, the sequel Maus II sat in ninth, and The Complete Maus (which includes both books) came in at number 2. A week earlier none had been in the top 1,000. Now they occupy three of the top 10. What happened?

A school board in Tennessee voted to ban the Pulitzer-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust.

The novel is the work of Art Spiegelman, who was born shortly after World War II to Polish Jewish parents who had lost a son and numerous family members in the war and the Holocaust. Maus came out of interviews Spiegelman did with his father about living as a Polish Jew and surviving the horror of the Holocaust.

But the McMinn County School Board voted 10-0 this month to ban the book from use in middle school. Apparently they didn’t like that the book included some profanity (though 80% of people in that county voted for a famously profane president in 2020). They also complained about the “nudity.” We put nudity in quotes because in this graphic novel the naked Jews being marched through a concentration camp are black-and-white drawings of mice (while the Germans are cats, the Poles are pigs, the Americans are dogs, and the French are frogs). One of us (Brian) read the Maus books in middle school and remembers them as enlightening and impactful — and he turned out okay (unless you ask Al Mohler).

Spiegelman responded by calling the ban “a red alert.” He added about the attention the school board vote brought to the book and issues about teaching history: “I’m grateful the book has a second life as an anti-fascist tool.”

Censoring a book about Nazis and the Holocaust does seem quite ironic at best. Interestingly, this wasn’t even the first time someone tried to ban Maus. Under the rule of Vladimir Putin, Russia targeted the book in 2015 — which quickly boosted sales.

But the desire to ban books in school isn’t limited to one graphic novel in a single Tennessee county. Rather, we’re seeing a push in school districts around the country to ban various books because of complaints about content. Last fall, the American Library Association reported a 60% increase in challenges to books over the previous year.

The pressure has not abated. For instance, a county in Florida is targeting 16 books for removal, and more than 20 books are facing calls for banishment from school districts in St. Louis, Missouri. A lawmaker in Texas even compiled a list of about 850 books he thinks should be removed because they “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

And it’s not just books. Censorship demands also sparked controversy last week in public debates about the music and podcast platform Spotify and the e-newsletter company Substack. Both conservative and liberal activists have been arguing for the removal of voices with whom they disagree.

In this issue of A Public Witness, we open up the book on recent efforts to ban or deplatform unwanted perspectives. Then we turn the pages on the ways these efforts often backfire, proving to be a harmful approach for dealing with noxious opinions.

Deplatforming

Back in 2020, Joe Rogan signed a $100 million-plus deal with Spotify to exclusively air his podcast, The Joe Rogan Experience, on their platform (we’re willing to take just a tenth of that amount for the rights to Dangerous Dogma). Upon inking the deal, the host reassured his fans that “it’s just a licensing deal, so Spotify won’t have any creative control over the show.”

Spotify might be regretting that hands-off approach. While Rogan’s podcast was the most listened to show on the platform in 2021, this year has brought far more turbulence to the relationship between Spotify and its star host. Artists like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell are taking their music off the streaming service. The author and social scientist Brené Brown is refusing to release new episodes of her Spotify-exclusive shows. With the momentum growing, others are likely to join the campaign.

They are all protesting what is said on The Joe Rogan Experience, especially the dissemination of falsehoods and misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines. Rogan has hosted noted conspiracy theorists and pushed unproven treatments popular among those resisting vaccination. As a result, hundreds of doctors and other medical experts are speaking out.

“With an estimated 11 million listeners per episode, JRE, which is hosted exclusively on Spotify, is the world’s largest podcast and has tremendous influence,” they wrote in a letter to the company. “Spotify has a responsibility to mitigate the spread of misinformation on its platform, though the company presently has no misinformation policy.”

Over the weekend, Rogan offered a generic (non-apology) apology and a vague commitment “to balance things out.” Spotify released its content guidelines publicly and pledged to apply labels to certain controversial content, but it joined other social media and tech companies in arguing its service was more platform than media outlet. CEO Daniel Ek stated in an open letter, “It is important to me that we don’t take on the position of being content censor.”

(Jonathan Farber/Unsplash)

Spotify is not the only communications platform facing such criticism. Substack — used by us to deliver this content to you — is facing similar denunciations. The Center for Countering Digital Hate, a British nonprofit that tracks online misinformation, recently highlighted how the platform for subscription newsletters receives financial profits from the newsletters of vaccine skeptics and other COVID-19 conspiracy theorists. Such content is “so bad no one else will host it,” claimed Imran Ahmed, the Center’s CEO, in a moment of exaggeration.

Lulu Cheng Meservey, Substack’s vice president of communications, pushed back in a Twitter thread: “When it comes to bad ideas, it’s neither right nor smart to martyr them and drive them into dark corners where they’re safe from examination and questioning.”

“Who should be the arbiter of what’s true and good and right?” she asked before adding an allusion to Harry Potter. “People should be allowed to decide for themselves, not have a tech executive decide for them. That doesn’t work. What works is examination and mockery (like using the Riddikulus charm against a Boggart).”

The founders of Substack also explained how their platform differed from social media sites like Facebook. The latter makes money off advertising, and thus allows people to pay Facebook to show people content — even content from pages people didn’t want to follow. Additionally, Facebook’s algorithm will also help spread non-promoted pieces that are popular because the company wants you to spend more time on the app (so they can sell more ads). Substack, on the other hand, makes money off subscriptions. Thus, they only send you the content for which you subscribe. If you don’t want to see COVID misinformation, you simply don’t subscribe to such newsletters.

“Our promise to writers is that we don’t tell them what to do and we set an extremely high bar for intervening in the relationships they maintain with their readers,” Substack’s founders explained last week. “We will continue to take a strong stance in defense of free speech because we believe the alternatives are so much worse. We believe that when you use censorship to silence certain voices or push them to another place, you don’t make the misinformation problem disappear but you do make the mistrust problem worse.”

Like a game of whack-a-mole, the COVID misinformation keeps popping up, and thus so do the calls for deplatforming.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

An Equal & Opposite Reaction

We believe that those who refuse to get vaccinated against COVD-19 foolishly risk their own lives, irresponsibly strain our shared health care resources, and dangerously threaten the health of others. Moreover, we abhor those cynically spreading falsehoods for their own financial gain. At Word&Way, we’ve been arguing and working for Christians to lead by example throughout the pandemic.

Additionally, neither of us have listened to an episode of The Joe Rogan Experience. We knew he was disgusting long before he gained even more fame through podcasting. Nor have we subscribed (even for free) to any Substack newsletters undermining public health.

However, our organization does use both Spotify and Substack in advancing its mission. We depend on these platforms to get our views out and our voices heard. That’s why we’re critical of the critics. They have the right diagnosis but the wrong prescription. While we think Spotify shouldn’t invest in Rogan, we also think Neil Young went too far by demanding the removal of the show from the platform. As Jack Shafer, Politico’s senior media writer, put it, “Young’s public and messianic urge to mute a speaker, his attempt to protect other people from speech he deems harmful, cuts against his own career-long devotion to free speech.” It also doesn’t work.

Efforts to ban books, censor content, or deplatform voices often actually help those it intends to hurt. Some people call this the “Streisand effect.” And, no, it has nothing to do with the hit songs “Woman in Love” or “No More Tears.” But it is a story about Barbra Streisand.

In 2003, she sued a photographer who posted more than 12,000 images online that he took of California’s coastline as part of a project to document coastal erosion with the hope of strengthening environmental advocacy efforts. But the die-hard liberal singer didn’t like it. Or rather she didn’t like one image that happened to show her own beachfront mansion. So, she demanded the image’s removal from the website. She eventually lost the suit and had to pay the photographer’s six-figure legal fees. But that’s not where she really lost.

Prior to her suit, that image of her mansion had only been downloaded from the coastline website six times (two of which were by her own attorneys). After her lawsuit sparked media coverage, more than 420,000 people checked it out over the next month. Thus was born the “Streisand effect.” By trying to remove an image so people wouldn’t see it, she instead inspired hundreds of thousands of people to go see it.

Maus on Amazon this week proves the effect still occurs. Ditto for Joe Rogan. We checked Google trends for searches about him. January 2022 was his most popular month ever.

Not that this should surprise anyone paying attention. Because Streisand wasn’t the only cautionary tale. For example, after the French intelligence agency tried to delete a Wikipedia page about an obscure military radio station, it briefly became the most-read French-language entry. Or remember when then-U.S. Rep. Devin Nunes filed a lawsuit against an anonymous parody cow Twitter account? The lawsuit against the account, Devin Nunes’ cow, sparked some udderly bad puns mocking the congressman. The attention to the account’s beef with him also helped it grow from around 1,200 followers to more than 770,000. Holy cow, if we could get a congressman to attack our Twitter account that would really moooo-ve our numbers! (Sorry, please don’t cancel us.)

A second problem with our society’s reflexive impulse toward silencing or deplatforming “unwanted” voices is figuring out who gets to decide what should be censored. Once we create a precedent of removing some individuals because of their content, it means others could also be forced out. These unintended consequences mean that those celebrating the canceling of others today could become the target tomorrow.

Consider for instance a proposed bill in Arizona that would ban any book from public schools that depicted “sexual conduct” like “homosexuality” or “sexual intercourse.” After some noted that could result in banning the Bible, the House Education Committee added an exception for “classical literature.” In Oklahoma, the Bible might be less safe. A proposed bill there would require public schools to remove a book if even just one parent complains about it because of sexual content — and if the school doesn’t remove the book within 30 days, they face a daily $10,000 fine. What are they going to do when a parent complains about the Bible because of Song of Songs or the various depictions of sex and even rape?

Or after we remove COVID disinformation from podcasts on Spotify and newsletters on Substack, who gets to pick the next target? If some of the top-streamed artists on Spotify — like Adele, Justin Bieber, Drake, and Taylor Swift — decided to launch a public relations campaign against Dangerous Dogma, it would be “Bye, Bye, Bye” for us unless Spotify refuses to allow the musical mob to decide who’s allowed on the platform (and, yes, that pop reference accurately dates us).

These examples might seem silly, but one person’s truth is another’s misinformation. As we saw with the last presidential administration, even real news can be labeled “fake” and government resources can be used to present misinformation about history and more. Do we really want to let a few people — in Washington, D.C., or Silicon Valley — decide which content is allowed?

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

A Better Way

In Plurality and Ambiguity, theologian David Tracy argues for a particular approach to the interpretation of texts, events, and people. Our understanding of such things is rooted in conversation and debate, which comes with certain ground rules. To have a conversation requires being open to conversion. It implies one is willing to listen to someone else and have their mind changed (or not) as a result.

“Persons willing to converse are always at one major disadvantage from those who are not,” Tracy wrote. “The former always consider the possibility that they may be wrong.”

One common denominator to school board book bans and COVID-19 conspiracy theories is the people enacting or peddling them have too many followers. Marginal ideas once dismissed as fringe and extreme have taken center stage. More problematic than what Joe Rogan says is how many millions of people are listening. Deplatforming him won’t change that dynamic. He will find another venue and the controversy only attracts more listeners now made curious by the kerfuffle.

Instead of making censorship our first instinct, we instead should confront the root source of the problem. Within the Church, that means recognizing that too many Christians are enthralled by the misogyny, mistruths, and other sins embraced with pride on Rogan’s show. It also means realizing that elected leaders seeking to suppress challenging and perhaps uncomfortable ideas enjoy too much political support.

For Christians, these cultural flashpoints are opportunities to persuade and correct. Instead of giving into the tribal impulses that seem to overwhelm our collective thinking, we should look to the Apostle Paul as our model. He debated those of other beliefs in Athens because he was confident in the truth he preached and the God he served. After condemning what is destructive, let us seek to convince, reconcile, and redeem rather than resort to attempts at censoring that inevitably perpetuate the problem.

As conservative commentator David French, who writes the French Press newsletter on Substack, tweeted yesterday: “This nation cannot censor its way to cultural or spiritual or political health.” That’s even more true for the Church.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood