“Started out this morning in the usual way.”

With the guitar playing and those words belting out over the large speakers, Pennsylvania Republican gubernatorial nominee Doug Mastriano walked toward the podium at a massive campaign rally. It’s a pretty usual way for the state senator to approach a podium, especially at big events — like on the afternoon of Sept. 3 at a rally featuring former President Donald Trump.

“Chasing thoughts inside my head I thought I had to do today. Another time around the circle, try to make it better than the last.”

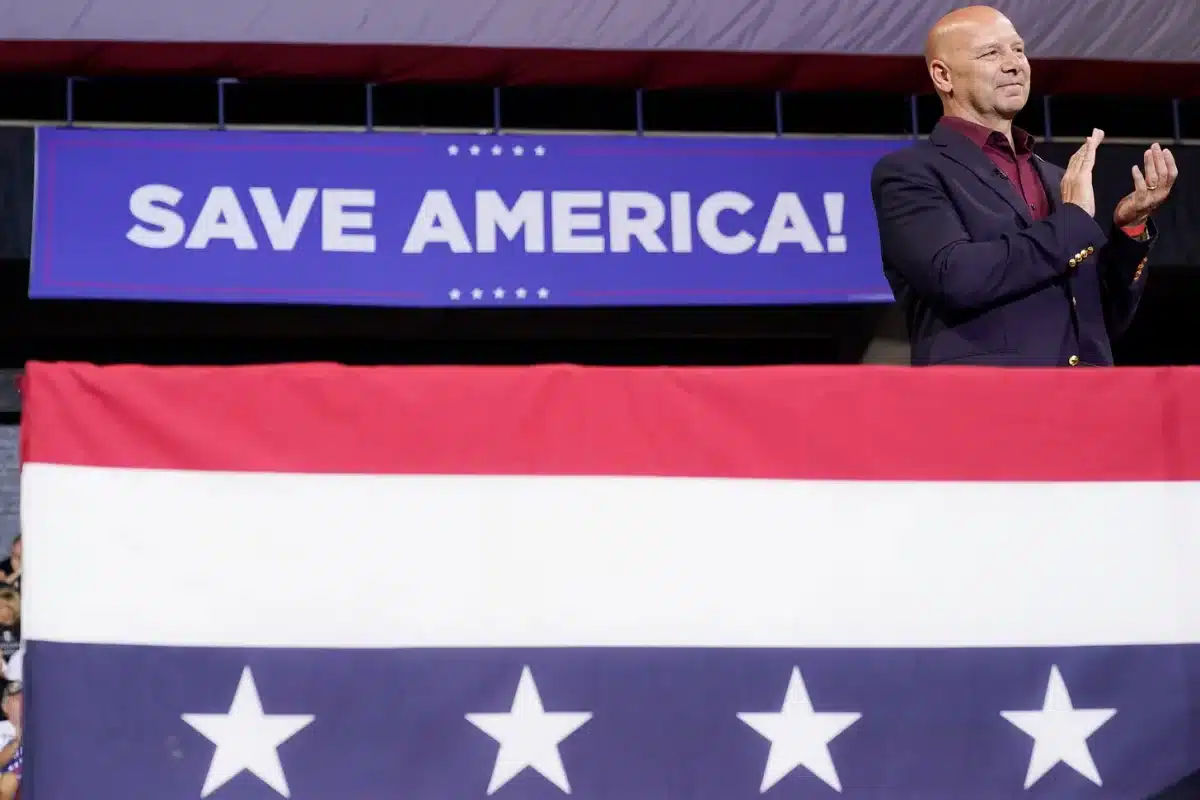

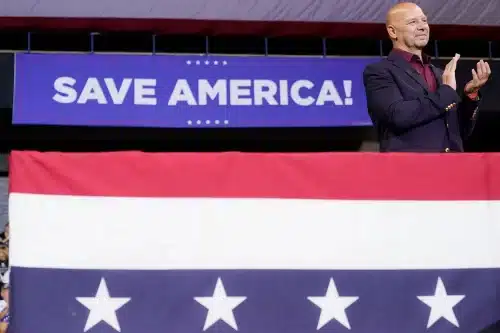

As Mastriano and his wife waved to the cheering crowd, the song continued. They made it to the podium where a sign declared, “Save America.” As he waved and pointed at people at the rally, one more line played before the music suddenly stopped.

“I opened up my Bible and I read about me.”

That line from the classic Steven Curtis Chapman song “The Great Adventure” takes on new meaning as an anthem for Mastriano’s campaign. Perhaps the poster child for Christian Nationalism in the 2022 midterms, Mastriano might just think this song is about him.

For Chapman, it’s a song about each Christian recognizing the call to follow Jesus as sinners saved by grace. Since we came of age with Chapman’s voice dominating Christian radio, we know that the chorus even switches to a plural reference as Christians blaze the trail together to “follow our leader into the glorious unknown.” Borrowing cowboy references as a fun lyrical metaphor — with horses, mountains, and western ranches making the point in the music video — Chapman offers a fun, peppy exhortation for Christians to joyfully live the Christian life. It’s basically like the biblical “armor of God,” a metaphor to encourage Christians, not a literal call to arms for partisan warfare.

But with Mastriano playing this song, the tune seems to shift in light of his campaign rhetoric about faith and government. And it wasn’t a coincidence he strolled out to “The Great Adventure.” At carefully-scripted rallies like the one with Trump, everything is preplanned. Who speaks and in what order. What the backdrop should be, including how many American flags to put up and which audience members to invite to stand behind the speakers while holding signs provided by the campaign. And which song each speaker will hear as they walk across the stage. At the rally with Trump, Mastriano also walked off to a reprise of the same song.

Pennsylvania Republican gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano speaks ahead of former President Donald Trump at a rally in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, on Sept. 3, 2022. (Mary Altaffer/Associated Press)

Additionally, we know Mastriano likes this song for his events because it wasn’t the first time we’ve heard it. He used it as his intro music at the event officially announcing his candidacy (an event that also included the blowing of a shofar, prayer, live music by Christian musician Danny Gokey from American Idol, and remarks by Michael Flynn). And as we reported in May, Mastriano’s remarks at his primary victory party were bookended with “The Great Adventure” blaring over the speakers. He even worked in a reference to the song in his victory remarks just before it played: “Take a couple days off and then the great adventure continues until ultimate victory on Nov. 8.” Chapman’s great adventure of living for Jesus was saddled with a new goal of winning a partisan horserace.

Mastriano sees his campaign as part of a divine mission. He puts a Bible verse on his campaign signs (John 8:36) and frequently invokes the passage as a guiding theme for his candidacy. His campaign’s even selling Christmas ornaments with the message ripped from the Bible (though out of context since the freedom John speaks about isn’t what the Constitution’s Bill of Rights offers). The candidate also insists God is on his side.

“We have the power of God with us. We have Jesus Christ that we’re serving here. He’s guiding and directing our steps,” Mastriano declared at a “prophetic” event in April. “In November, we’re going to take our state back. My God will make it so.”

“I opened up my Bible and I read about me.”

Mastriano’s adventure up to this point includes a long, out-of-tune verse about the 2020 presidential election. Mastriano refuses to accept that President Joe Biden actually won. So, he joined Rudy Giuliani shortly after the election to host a “hearing” in Gettysburg in an effort to cast doubt on Biden’s victory in the state. He pushed government officials to investigate alleged “fraud,” proposed ways to change the state’s electoral votes, and met with Trump to discuss ways to change the election results.

But he wasn’t content to just sit in Pennsylvania and try to overturn a free and fair election. So, Mastriano went to Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021, and even bused others there to join the pro-Trump mob.

He continues to preach this false gospel of election fraud on the campaign trail. As he declared at the rally with Trump and the Chapman song, “We’re going to fight like hell for voting integrity.”

The main figure who fomented and cheered the insurrection hit similar notes at the rally. Trump repeatedly insisted he won the 2020 election, the big lie that inspired the attack on the Capitol. And he argued that Democrats can only win if they “cheat like hell on elections.” And Trump praised the man who came onto stage to Chapman’s song promising that “the love of God will take us far,” saying that Mastriano “fought like very few people fought, that’s really why he’s here, because everybody saw that. He fought.”

Which leads us back to Chapman’s song (still running in our heads for this whole piece, “Whoa Whoa”). We know who Mastriano is and what he believes. But does Steven Curtis Chapman want his music associated with such a campaign? So, in this issue of A Public Witness, we dust off our old Chapman cassette tapes to consider the different testimony he offers about faith and even Jan. 6. Then we record our own ballad to remind Chapman there’s a trail to blaze in this less than glorious moment.

The Man Behind the Music

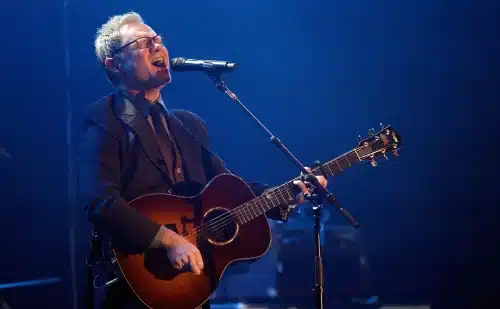

In the world of contemporary Christian music, Steven Curtis Chapman is a giant. His songs are familiar to anyone who listened to Christian radio in the 1990s and 2000s. Few artists have exerted greater influence on the U.S. evangelical subculture.

Chapman scored his first major CCM hit with “His Eyes” in 1988, which the Gospel Music Association named its contemporary song of the year and helped earn him the award for songwriter of the year. Subsequent albums like For the Sake of the Call, The Great Adventure, Heaven in the Real World, and Speechless would climb to the top of the Christian music charts.

In terms of Dove Awards, which is the Christian music industry’s equivalent of a Grammy, his 59 awards make Chapman the most decorated artist of all time (and, by the way, he’s also won five Grammys). After recording 49 #1 singles and selling more than 11 million albums, the music company BMI recognized Chapman with their Icon Award. The first Christian music artist to receive the award, he joined a prestigious list of winners that includes Barry Manilow, Dolly Parton, and Busta Rhymes.

Steven Curtis Chapman performs at the 47th Annual GMA Dove Awards at on Oct. 11, 2016, in Nashville, Tennessee. (Wade Payne/Invision/AP)

That stature and influence makes his music an obvious choice for politicians who identify with and seek support from White evangelical Christians.

“I am not surprised to see something by Steven Curtis Chapman on the campaign trail this election cycle — especially for a candidate like Doug Mastriano,” Dr. Leah Payne, an American religious historian whose forthcoming book examines the conservative Christian music industry, told us. “CCM has, historically, been a lot like Country music (another Nashville-centric music industry): performed mostly (but not exclusively) by White singers, entertainers, and artists, with a default political conservatism usually attached to it. So, it makes sense that someone in the Mastriano campaign (maybe the candidate himself) would choose an iconic CCM hit as his intro music.”

Mastriano has even repeatedly shared Chapman videos on his campaign Facebook page (including, of course, sharing “The Great Adventure” multiple times over the past year). Additionally, in several livestream videos — a hallmark of his campaign approach as he eschews traditional media — he played the song while offering campaign updates and thanking those watching and chatting live.

In a Christmas Eve stream last year as he talked about launching his campaign, he played the song and declared, “Oh yeah, it’s going to be a great adventure, that’s for sure.” Moments later, with the song still playing, he added, “This will be our theme song this campaign.” And he mentioned he was trying to get Chapman to come for the campaign but needed help making the connection (instead he had to settle for Gokey). In another stream, he played the song twice as his wife sat next to him mouthing the words as he read online comments. He added in the video that running for governor was him deciding to “saddle up our horses.”

Less clear is whether Mastriano realizes his own actions and beliefs related to Jan. 6 are at odds with Chapman’s response to the insurrection. Chapman, who had performed at the White House in 2017 for the National Day of Prayer, was (like most of us) upset by what he saw occurring as Congress met to certify Biden’s election. Shortly after mob violence broke out at the Capitol, Chapman shared his thoughts on Facebook.

“Words can’t describe the sadness that I feel as I watch the events currently unfolding in our country. I’m so heavy hearted at the brokenness and division that we are witnessing and experiencing in our world today,” he wrote that day. “Now more than ever before, it seems like the soul of our world (& our nation) is aching, longing and desperate for PEACE.”

“I am processing in the way most natural to me as a singer-songwriter: with a song,” he said in introducing a new song, “A Desperate Benediction,” on Jan. 6 before the shattered glass and human feces had even been cleared from the Capitol. Its lyrics proved a timely witness:

Let there be peace, let there be peace on

The babies being born and the roses on the grave

The losers the winners, the fearful and the brave

We’re all brothers and sisters crying to the Father for

Peace on earth, peace on earth

Oh let there be peace on earth

Oh let there be peace on earth

And let it start with me

Other Christian musicians joined Chapman in speaking against the antidemocratic violence that erupted that day by allies of Trump and Mastriano.

“Do we believe in the democratic process?,” asked Switchfoot lead singer Jon Foreman. He called the riot an “epiphany on the calendar” (an analogy we believe is apt) and urged Americans “to look at ourselves in the revealing light of the violence we witnessed.”

Pushing back against the idolization of political power, hip hop artist Lecrae told his social media followers, “There is a lesson here about what true power looks like. There’s an invitation to listen to the story that God is telling with his voice. There’s a powerful challenge to issue to our hearts about what matters most to us. There’s a message about the seduction of empire, the illusion of control, and the allure of power.” He added, “The Kingdom will have a King who will righteously rule. The empire is going to fade away. And I think a lot of people are caught up in the empire right now.”

A lot of people indeed. Including some running for office.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Musical Showdowns

Curious to know what Steven Curtis Chapman thought of his music being used to bolster Mastriano’s campaign, given their apparent differences in tone and views about Jan. 6, we reached out repeatedly to his publicist but did not receive a response. Between the media attention Mastriano’s campaign received and our inquiries, it is hard to believe Chapman and his team are entirely unaware of how his music is being used. And if he doesn’t like the use of his song, it wouldn’t be the first time a musician encountered this dilemma.

Controversies between candidates and artists are a regular feature of political campaigns. Bruce Springsteen famously quarreled with Ronald Reagan in 1984 after the release of “Born in the U.S.A.” Music by the Boss is regularly used by Democratic candidates to appeal to White working-class voters. Springsteen even narrated a campaign ad for Joe Biden in 2020 focused on the now-president’s Scranton, Pennsylvania, roots.

John McCain faced some of the strongest pushback from musicians whose songs he wanted to use in defining his campaign. Jackson Browne sued McCain (and won both a settlement and a public apology) when “Running on Empty” appeared in a campaign ad without the artist’s permission. McCain also faced criticism from musicians like Foo Fighters, John Mellencamp, and Eddie Van Halen for using their music in his 2008 presidential bid.

Sarah Palin, McCain’s running mate, also came under fire over her playlist. Nancy and Ann Wilson of the band Heart used some choice words to express their opposition to “Barracuda” being used at Palin appearances. Likewise, country music writer Gretchen Peters objected to Palin’s use of her hit song “Independence Day” because of the GOP’s stance on abortion. Peters donated her election-related royalties from the song to Planned Parenthood in Palin’s name.

Democrats are not immune from musical critique. The R&B artist Sam Moore asked Barack Obama to drop “Hold On, I’m Comin” from the candidate’s rallies in 2008. Obama complied and, in a twist of irony, Moore ended up performing at one of Obama’s inaugural balls and, later in his presidency, at the White House.

And numerous musicians criticized and even sued Donald Trump for using their music, including Neil Young, R.E.M., Aerosmith, Adele, Elton John, Queen, The O’Jays, The Rolling Stones, Twisted Sister, Guns N’ Roses, and Nickelback. While some don’t want their songs used in any political campaign, others noted they specifically did not support Trump’s policies and did not want people to think otherwise.

For instance, the legal team for Rihanna made this point as they sent a cease-and-desist letter to Trump for using her songs at rallies. Their letter argued the usage of her songs “creates a false impression that Ms. Fenty is affiliated with, connected to, or otherwise associated with Trump.” Rihanna also tweeted her disapproval to further distance herself from Trump.

Former President Donald Trump is joined by Pennsylvania Republican gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano on stage at a rally in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, on Sept. 3, 2022. (Mary Altaffer/Associated Press)

Which brings us back to Steven Curtis Chapman. Like some of the musicians who have complained in the past, he might not have a legal avenue if Mastriano obtained a license to use the song through some other party. But Chapman still has the moral authority of his public voice — as he demonstrated with his response to the Jan. 6 insurrection that Mastriano attended.

Since our private messages have gone unanswered, we’ll add a public call for Chapman to disavow the use of his music by the Mastriano campaign and make it clear he does not support the conspiratorial politics of the Pennsylvania politician. Larry Norman famously asked, “Why should the devil have all the good music?” We similarly wonder why secular artists are the ones leading the way in condemning the exploitation of their music by politicians.

When those pushing election lies, COVID-19 conspiracies, and heretical Christian Nationalism co-opt your music, you have a moral responsibility to speak out and offer the alternative witness of the Prince of Peace. So, we hope Chapman — and other Christian musicians who find their songs employed in such partisan ways — will speak out not just for their music but for the sake of the gospel.

Please, Mr. Chapman, the time to be speechless has passed. Saddle up your horses, you’ve got a trail to blaze.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood