Last year, Samford University in Alabama canceled a speech by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and Episcopal layman Jon Meacham due to objections from conservative Christians. This year, the school canceled his entire denomination.

More specifically, campus chaplains connected to the Episcopal Church and Presbyterian Church (USA) were denied space at a Church & Ministry Expo held on campus on August 31. A Baptist minister of a theologically progressive congregation also detailed her exclusion.

“We’ve done some version of Episcopal campus ministries and have been active at Samford for over 30 years. We have regularly participated in the ministry fairs,” Rev. Kelley Hudlow of the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama said. “We are not allowed to do ministry on campus currently.”

The banishments appear related to the pro-LGBTQ stances of the respective denominations and ministries. According to Brit Blalock, founder of Students, Alumni, and Faculty for Equality at Samford, the Samford campus pastor who disinvited the groups “was explicit in saying that the reason was [one of the chaplain’s] denomination’s affirmative stance on LGBTQ people and did not mention any policies she was in violation of.”

The university responded by sending a letter to students claiming, “Throughout its history, the university has consistently subscribed to and practiced biblically orthodox beliefs.” The letter from Vice President of Student Affairs Philip Kimrey added that “the university has a responsibility to formally partner with ministry organizations that share our beliefs.”

Reid Chapel at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. (Creative Commons)

Samford’s track record on LGBTQ issues is decidedly muddled. After provisionally recognizing an LGBTQ student group in 2017, the school faced backlash from the Alabama Baptist State Convention. Responding to the controversy, the administration refused to grant permanent status to the group and also declined funding from the Convention. Recommendations of a presidentially-appointed study group on sexuality have gone ignored.

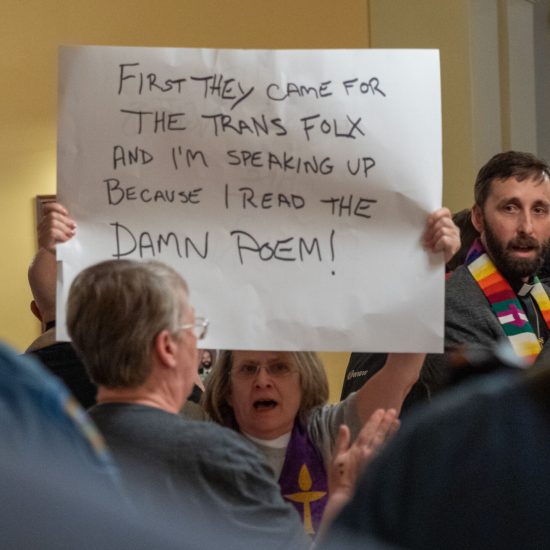

After the new move excluding some groups from campus ministry, students led a protest outside the school’s mandatory weekly convocation service. And alumni are organizing a letter-writing campaign to the president, urging him “to return Samford to the ecumenically diverse and respectful campus it has been for decades.”

But something is missing from this conversation. Despite its claims to the contrary, the school has not “consistently subscribed to and practiced biblically orthodox beliefs.”

In this edition of A Public Witness, we take a closer look at the university’s past and find that its current justifications for excluding other Christians from campus rest on a revisionist whitewashing of its own history. After naming Samford’s struggle to face the ghosts in its proverbial closet, we look at attempts by other Christian institutions of higher education to exorcize similar demons. Then we consider the prophetic witness that Samford needs to heed, which actually emanated from its own campus this summer.

Samford’s Enslaver History

First up is Edwin D. King, introduced as “a planter, businessman, and philanthropist.” He helped found the school, served on its board, and gave it lots of money. But we also find a caveat that helps explains his wealth: “Although Edwin also became a cotton planter with thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves, it was his investments in local businesses and schools that consumed much of his time.”

We checked the census data to learn more about King. In 1840 — the year before he helped start and fund the school — he enslaved 164 persons. There shouldn’t be any questions about how he obtained the money with which to be generous.

The second founder Samford lists is Rev. James Harvey DeVotie. He donated some land for the school’s first campus and served on the board of trustees. Although his biography on the site details numerous aspects of his ministry, including churches he pastored in Alabama and Georgia, it leaves out one role: his four years as chaplain in the Confederate Army. In fact, the biography jumps right from his pre-war church to his post-war church: “During his tenure in Columbus, and later at the Baptist church in Griffin, DeVotie emerged as one of the most important leaders in the Georgia Baptist Convention.” There’s a lot left unsaid in that comma between Columbus and Griffin.

We again checked the census data. In 1860, just before he served in the Confederacy, DeVotie enslaved nine persons while he also served as pastor of First Baptist in Columbus, Georgia. Samford’s online biography of him does not mention he enslaved people.

Samford’s third honored founder is Julia Tarrant Barron, who they note “became one of the wealthiest women in Marion.” Widowed several years before the founding of the school, Samford says Barron received “a large estate” from her late husband who was “a prosperous businessman.” She is credited not only with significant donations but also with bringing people together to plan the college’s launch.

But Samford’s history section doesn’t note a key part of her wealthy estate. The census data for the year before the school started reveals she enslaved 35 persons.

The fourth key founder Samford honors is Rev. Milo P. Jewett. The history section highlights that he had to leave Alabama and move to New York in 1855 “for political reasons” since “it was clear Jewett’s abolitionist beliefs did not fit in with the goals of the Southern Baptist Convention.” But there’s another side of Jewett left out. He also enslaved people.

We checked the census data and found that in 1850 he enslaved seven persons. The longer biography of him from Vassar College — the school he helped start and led as the first president after he moved to New York — offers a bit more detail, although with inaccurate language that downplays slavery: “Perhaps sensing the tensions which would culminate in the Civil War, Jewett relocated to the north, offering freedom to his own servants if they chose to move with his family.”

Beyond the key founders, a look at early presidents also reveals this trend in its history. Although Samford’s history site doesn’t mention it, the school’s early presidents were all enslavers.

The census data shows that Samuel Sterling Sherman, the president for the first decade, enslaved four persons in 1850 while president (two of whom would have been the ages of students on campus, though the school only accepted White students).

The school’s second president, Henry Talbird, led the school from 1853 until he left in 1862 to fight in the Confederate Army as a colonel. Just before the Civil War started, the census data shows that President Talbird in 1860 enslaved 10 persons, including a male the age of the students on campus.

We know a bit more about one of the individuals he enslaved. Harry is honored on Samford’s campus today because he died in 1854 while saving students from a fire. The school has evolved in the way it honors him. An older marker on campus referred to Harry as “college janitor and servant of President Talbird.” The new marker acknowledges slavery (though is generic about by whom): “an African American man who lived in slavery.”

After a leadership gap of a couple years as the president (and many of the students and faculty) left to fight for the Confederacy, the school’s third president started in 1865. Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry had resigned from the U.S. Congress when Alabama seceded from the Union, and then he fought in the Confederate Army. After the war, he became the president of the state Baptist convention and then of the college. But just before the war, the census data appears to show he enslaved 37 persons (there are two records with his name, one documenting 29 people and one on the next page showing another 8 in a separate entry, but he’s the only person by that name in the census for the county).

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.