A few months ago, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a historian at Calvin College and author of Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, pulled back the curtain on a topic that has long fascinated me: how prominent authors handle requests for book blurbs.

There are weird dynamics around gaining additional exposure without oversaturating one’s influence in a way that ultimately weakens it. There’s also the more basic question of time and whether endorsers actually read the material they’re encouraging others to spend their limited time and money on.

Du Mez’s lengthy post is worth your attention because her approach cannot be fully summarized here, but she explained, “Call me old-fashioned, but I actually read the books I endorse.”

“I have a platform that isn’t massive but also not insignificant, and I try to use that to foster better conversations about things that matter,” she added. “Promoting academic books is a big part of that. I know full well what it’s like to labor as an academic for more than a decade to produce a deeply-researched book that very few people read.”

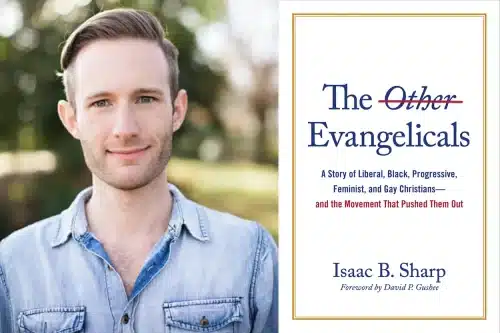

My reason for sharing all this is that Du Mez wrote a substantial blurb for Isaac Sharp’s The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians — and the Movement that Pushed Them Out. His book is an attempt to tell an alternative history of the evangelical movement. Du Mez wrote that the book “will quickly establish itself as one of the most important books on American evangelicalism in the modern era. An essential read.”

Given our confidence that she actually read the book before endorsing it and her status as an expert in this particular subject area, there’s little more this review needs to say. If you write a book on American evangelicals in the 20th and 21st centuries that Kristin Kobes Du Mez describes as “an essential read,” then you’ve accomplished something significant and others would be wise to take notice.

Still, it’s worth unpacking the story Sharp tells in a little more detail here. Scholars have demonstrated how evangelicalism in the United States was and is a constructed identity. The self-identified leaders of this movement — pastors, denominational figures, academics, journalists, and others — defined and then occupied a space between fundamentalism and Protestant liberalism.

Those who led this project in the middle of the 20th century, as Sharp wrote, “established what became the most widely accepted understanding of what contemporary evangelicalism actually was: an interdenominational movement of generally conservative Protestants united around a set of theological commitments” that fostered a sense of common identity.

Yet, he added, the movement was “faced with a profound identity crisis from the outset” because of “significant internal diversity” among Christians who claimed the evangelical label. Thus, the boundaries of evangelicalism in the United States have always been contested, policed, and, at times, redefined.

As a result, the movement’s history is filled with episodes of tension and exclusion. Sharp’s subtitle succinctly captures this, while different chapters of the book detail the way specific groups were marginalized within or ostracized from the community by those with the power to delineate who (and what) qualifies as “evangelical” and who (and what) does not.

Some of the historical ground covered in the book will be familiar to those who have experienced or watched these events unfold over the last 50-plus years. Others may be less well-known but illuminate the story in clarifying ways. Taken as a whole, Sharp’s project provides an impressive account of the evangelical movement by focusing on those who were drawn outside of its boundaries.

The ultimate consequence is a self-defined tradition mired in crisis because of the increasingly narrow strictures it places upon itself.

“By the dawn of the twenty-first century,” Sharp concluded, “the most evangelically acceptable version of U.S. American evangelical identity, for instance, was someone who believed like an antimodernist antiliberal inerrantist, thought like an anti-feminist antigay complementarian, and voted like a White Republican.”

This book spends its time looking back on what has been rather than focusing on what might be. What it makes clear is those wanting to redeem the evangelical label will face substantial headwinds in widening the tent. The reason there are so many ex-evangelicals is less about people choosing to exit the movement and more about the movement being consistently recast in such ways that fewer Christians see themselves included in what it came to represent.

If you want to understand more about what inspired Sharp to write this book and the specific arguments he makes within it, we interviewed Sharp about The Other Evangelicals on a recent episode of our podcast Dangerous Dogma.

Every month we give away a signed copy of the book (by the author, not by me) to a paid subscriber of A Public Witness. This month, we’re happy to make available a signed copy of what Du Mez called “an essential read.”

So upgrade today and you’ll also help sustain our work writing about the intersection of faith, culture, and politics. We’ll be selecting this month’s lucky winner of The Other Evangelicals at the end of this week.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood