“Every time the church seeks to align itself with either existing powers that be or [those] aspiring to power, it actually loses.”

Croatian theologian Miroslav Volf offered that word of warning last week in Stavanger, Norway, during a joint gathering of the Baptist World Alliance’s annual meeting and the European Baptist Federation’s “Sent” mission conference. The director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture explained why the quest to align with power backfires.

“We think we will gain because we might gain influence, but actually we corrupt the gospel in search for acquiring and maintaining power,” he said. “And pretty soon, a generation that comes after won’t have anything to do with it because they no longer identify with the project, and then the faith gets discarded on the count of its association with the particular political or cultural project.”

Volf, an Episcopalian whose father was a Pentecostal pastor, added that this is one reason he says “there is a strangeness to the gospel.” But too often, he lamented, the church doesn’t reflect the values and teachings of Jesus.

“Christ has in a sense become a moral stranger to our culture,” he argued. “Most of the things that matter to our culture a great deal didn’t matter to Jesus one bit. And most of the things that mattered to Jesus a great deal don’t matter to us very much.”

That disconnect, Volf added, creates “a challenge for the wider culture and for the mission of the public church.” As an example of an area of difference in values, he mentioned money, which “we care about quite a bit.” But caring for money shows the mistake of caring more for the means than the ends.

“If you pursue means, then your means have a way of becoming ends, becoming goals. And money is the best example,” Volf said. “Money’s worth absolutely nothing. It’s worth nothing in itself. Its entire value is being the means to get something.”

Left: Miroslav Volf speaks in Stavanger, Norway, on July 4, 2023. Right: Dez Johnston, who works for Alpha in Scotland, speaks in Stavanger, Norway, on July 8, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

This obsession with getting more of something that is just a means shows, he said, that we have “forgotten how to ask the most important question of our lives.” Which is about meaning and purpose, not merely how to do something or how to “get from point A to point B.” By focusing on the means, “we are in this hamster wheel. And we constantly move, trying to get more and more means, better means — and actually never live a good life.” And just in case anyone missed the metaphor, he later added, the “hamster wheel has never been a good image for good life for human beings. Maybe for hamsters, but not for human beings.”

“We have become people who are obsessed with the means for life,” Volf said. “We become experts in means, but we have become amateurs in ends, in purposes.”

This approach can lead to a focus on relevance and power as “the world sets the agenda and we then respond to it.” But Volf sees that as “a kind of betrayal” by putting the world and its values in the position to judge what is right or needed.

“We live in a time of great tensions,” he added. “Economic tensions, cultural tensions, political tensions, wars, racial tensions, ecological tensions. You might say there is a kind of deep fissure or fissures that run within nations and between nations. … We are in a rupture.”

Volf argued that in such a moment, Christians must find their mission in the world. And that was the focus of the gathering as more than 800 people from more than 80 nations came together in Norway to consider what it means to be the people of God in the world today. Numerous speakers brought stories of what this alternative kingdom looks like and how it will differ from such versions of the church in the past.

Volf offered his remarks about the corrupting influence of power in a nation that long had an official state church but today sees few people actually attend any church. This issue of A Public Witness travels to Norway to hear from Christians who are wrestling with what it means to live and witness as a Christian in a post-Christendom society.

Clockwise from top left in Stavanger, Norway: Stavanger Domkirke (Stavanger Cathedral), the oldest church in town, which is being renovated ahead of its 900th anniversary in 2025; a downtown street; and Sverd i Fjell (Swords in Rock), a monument that remembers the battle there in 872 that brought all of Norway under one crown. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Shifting Church & State

Throughout the week, Norwegian speakers talked about issues impacting evangelistic work in their country. Since following the path of Martin Luther during the Reformation in the 16th century, the land of Norway has been officially Lutheran even as boundaries and who ruled them shifted. Even a constitution in 1814 that is generally considered quite liberal and democratic was not so when it came to religious liberty.

“[The constitution] still proclaimed that the faith of Norway should be the Lutheran faith,” explained Magnar Mæland, former head of Den Norske Baptistforening (Baptist Union of Norway). “To be Norwegian was to be a Lutheran. There was no freedom of faith.”

Early evangelicals or other non-Lutherans preaching in Norway faced restrictions on their worship and evangelism. Despite that, Mæland said, non-Lutheran churches and even Lutheran missionary societies not controlled by the Church of Norway continued to spread. This particularly occurred in the southwestern area of Norway, leading Mæland to call the region the “Norwegian Bible belt,” with Stavanger in the middle.

While the 2012 constitution officially ended Lutherans’ status as the state church, the Church of Norway is still financially supported by the government and it still has a privileged legal status with the king required to be a member (and the Church wasn’t created as a legal entity separate from the government until 2017). Thus, Mæland said, “still in many areas to be a Norwegian is to be a Lutheran. And when you are a Norwegian, you baptize your children in the church, you get confirmation in the church, you get married in the church, and you get buried in the church. But many Norwegians only go to church those four times.” So while two-thirds of Norwegians still claim to be part of the Church of Norway, only about 10% of them attend services at least once a month.

Inger Lise Salvesen, who is president of the Baptist youth ministry board, told me that because of this context, “We deal with a lot of people who have misconceptions about Christianity. They kind of have a familiarity to church, but they don’t really go there so they have all these conceptions of what they think it is about.” And for people from other countries, she added, it can be “quite confusing” because a lot of people “think that Norway is a Christian nation,” but few people actually practice the faith.

Sissel-Merete Berg, president of Den Norske Baptistforening, echoed that sentiment. She told me that people often “think that all churches are like how the state churches are. But it’s so different. We try to show them something else, and that’s not so easy.” In a way, she added, the non-Lutheran churches “have had to fight much more to be seen” and to not be derided as “a sect.”

But things are changing in Norway — and in the churches there. Multiple Norwegian ministers highlighted the growth they are seeing, largely because of immigration. An early wave came from Myanmar (formerly Burma), which brought a lot of Baptists who are part of persecuted minority groups like the Karen and Chin peoples. New churches of migrants started popping up, including in cities that previously didn’t have a single Baptist congregation. This and later waves of immigration from other countries have changed how Christians work and worship together. And the number of Baptists and other evangelicals in the country suddenly started to grow while the average age dropped.

Left: Sissel-Merete Berg, president of Den Norske Baptistforening, preaches during the opening Baptist World Alliance session at Tjensvoll Lutheran Church in Stavanger, Norway, on July 2, 2023. Center: Chin Bethel Baptist Church in Egersund, Norway. Right: Bjørn Bjørnø, general secretary of Den Norske Baptistforening, leads communion during the closing European Baptist Federation session in Stavanger, Norway, on July 9, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Sveinung Vaagen, who oversees leadership development for a youth ministry organization in Norway, said that while he grew up in a church with just ethnic Norwegians, today about 10% of the country’s population was either born abroad or have parents who were both born abroad. He added, “This percentage is increasing every year. The question is not if is this good or bad; the question is which new mission opportunities are made possible.”

“In the Baptist union, about one-third of the churches have a big majority of Norwegians. One-third of the churches are so-called migrant churches. Another one-third you can call multiethnic churches,” Vaagen added. “In Stavanger, the Baptists praise God in many different languages and worship styles.”

He sees the future moving to even more multiethnic churches, which is changing the Christian community and witness in Norway. And as “people of all tongues and tribes in Norway” worship together, “there will be a new kind of church you have never seen before in this country.”

Roald Zeiffert, who teaches theology at the Norwegian School of Leadership and Theology, also talked about how these immigration numbers are changing the way younger Norwegian Christians think in church — and in politics. His research explores how “young people in this changing world actually choose different ways to engage in both church with faith and in society.” He finds some students who combine what in other contexts might be considered conservative and liberal approaches. But even among the more conservative, immigration is the key issue that often differentiates young evangelicals in Norway from what might be seen in the United States. This is also impacted by the fact that migrant evangelicals tend to be more conservative than ethnic Norwegians.

Zeiffert noted that while one can find Christians voting for any of the couple of dozen political parties in Norway, his research shows that conservative young evangelicals are avoiding the far-right parties. That includes the party created in 2011 with the name Partiet De Kristne (The Christians Party), but that changed its name last year to Konservativt (Conservative). The party bills itself as anti-abortion, against same-sex marriage, and upholding what they call Norway’s “Christian cultural heritage” — and Zeiffert noted the party draws inspiration from the Republican Party in the United States. The party also advocates for anti-migrant policies, which keeps younger evangelicals who oppose abortion and same-sex marriage from supporting the party and instead backing a more centrist party that’s conservative on social issues but liberal on issues like immigration and climate change. As his research shows, young evangelicals — even those who are socially conservative — “are extremely politically liberal when it comes to migration.”

In this case, an experience in the church with refugees, migrants, and other oppressed peoples is acting to prevent a coalition with a political party seeking power on a platform focused on privileging ethnic Norwegian Christians.

(Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Resolved to Do Better

These missional challenges and shifts aren’t unique to Norway. Speakers from various nations — including Estonia, India, Israel, Lebanon, Sweden, and Syria — highlighted similar themes as they considered what it means to live as part of a minority tradition in their nation. Issues addressed included those posed by secularism, migration, war, technology, and younger generations.

Tomás Mackey, a longtime pastor and theology professor in Argentina, highlighted four key areas for missions that he’s seen while traveling the world as BWA president: those in severe pain, new generations, extreme polarization, and extreme secularism. All four themes were echoed by other speakers.

Among the current contexts of pain Mackey noted were Myanmar, Syria, and Ukraine (with leaders from all three countries present). For reaching new generations, he mentioned issues ranging from technological changes to discovering more effective ways to communicate.

When speaking about extreme polarization he sees rising in various nations, Mackey lamented that it results in “a breakdown of constructive dialogue and understanding between opposing sides” and leads many people who “do not agree with the extreme positions” to silence themselves and disengage. Sometimes, that silence comes because of pressure, intimidation, or even violence for holding a divergent opinion.

Similarly, Mackey warned, extreme secularism means “restrictions may be imposed on religious expressions” due to a “diminishing respect for religious liberty.” But he insisted that Christians must still engage in such contexts.

“Actively engage in works of mercy, social advocacy, and serving the marginalized and oppressed,” Mackey urged. “Become a place where individuals can experience forgiveness, restoration, and a renewed sense of purpose. Bear witness to the transformative power of God’s kingdom.”

This understanding of what it means to live as a minority without political power impacts how most attendees view how Christians should engage in public life. And it leads to a reassessment of older methods where missions and colonialism often arrived together. So the members of the BWA’s General Council passed a resolution addressing “dignity and justice for Indigenous peoples” (which I helped craft as chair of the BWA Resolutions Committee).

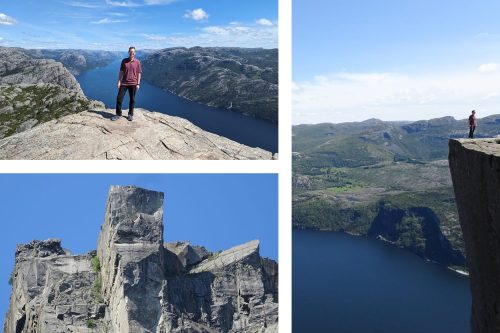

Preikestolen (Pulpit Rock) as seen from above and below. The flat top of the sheer cliff is 1,982 feet above the water of the Lysefjorden. (Word&Way)

The resolution starts by acknowledging the “the Sámi people of the Sápmi region, some of which overlaps with the modern nation in which we gather.” It also uses Indigenous terms for other land references, such as Turtle Island/North America and Aotearoa/New Zealand.

In addition to denouncing “the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ and any theological interpretation by Christians to justify the abuse, enslavement, and slaughter of Indigenous peoples,” the resolution condemns other injustices. This includes “centuries of mistreatment of Indigenous peoples around the world, especially the genocide and settler colonialism that decimated entire communities and cultures. Additionally, we denounce the seizure of land, treaty violations, forced migration, segregation, employment and religious discrimination, mistreatment by law officials, contamination of vital natural resources, and other injustices to which Indigenous peoples have been and are subjected.”

“Such efforts to bless the dehumanizing of people and the theft of their lands are fundamentally in opposition to the gospel of Jesus,” the resolution adds, while also pointing out that the Doctrine of Discovery continues to “remain embedded in some national laws, societal attitudes toward Indigenous peoples, and even in some Christian resources.”

As the resolution notes, “some Baptists and other Christians participated in the injustices against Indigenous peoples, including killing people, seizing land, kidnapping children, running residential schools or other institutions to eliminate cultures and languages, and restricting civil and religious rights.” But it also highlights some of the Baptists who advocated for Indigenous rights — like Roger Williams (Turtle Island/North America), John Saunders (Australia), and Silas Rand (Canada) — and some Indigenous Baptist leaders who served “even amid difficult circumstances, inadequate and inequitable support, and discrimination from other Baptists” — including Joseph Amos (U.S.), John Chilembwe (Malawi), Graham Paulson (Australia), and Truby Mihaere (Aotearoa/New Zealand).

Echoing language from last year’s resolution urging slavery reparations, the BWA in this year’s resolution “calls on Baptist churches, colleges, unions, and other institutions to study their own historical and present complicity with discrimination against Indigenous peoples, and urges more work toward restorative justice efforts to end discrimination against Indigenous peoples and repair the damage from past wrongs.”

When it comes to evangelism and discipleship today, the resolution demands such efforts “respect the humanity, culture, language, conscience, and land of each person.” Such a perspective differs dramatically from the injustices in the past and present. And it represents a refutation of the mindset of seeking power. Because as Miroslav Volf warned, “Every time the church seeks to align itself with either existing powers that be or [those] aspiring to power, it actually loses.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor