William Shakespeare’s Juliet believed that “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” But Russian authorities find roses to be quite dangerous. Police even arrested over 300 people in the past few days for quietly laying flowers and lighting candles. Their crime? Mourning the state murder of political dissident Alexei Navalny.

A lawyer and anti-corruption blogger, Navalny became a key leader of the political opposition to Russia’s authoritarian leader Vladimir Putin. After years of protests — and some time in jail — he announced a presidential campaign against Putin in 2016. He suffered multiple violent attacks, including one that left him mostly blind in one eye, and then Russian officials barred him from even appearing on the ballot. Putin “won” the “election” with 78% of the vote. Navalny spent more time in jail for protests of Putin’s inauguration and for protests against fraudulent local elections in 2019 — and was the victim of another chemical attack while in prison.

In August 2020, Navalny nearly died after yet another poisoning attack. After receiving medical attention in Germany, he returned to Russia, where authorities promptly charged him with various crimes denounced by international human rights groups as political persecution. Through it all, he remained strong in his beliefs.

“The fact is that I am a Christian,” Navalny declared during his closing arguments during his “trial” in February 2021.

As he continued his mini-sermon, he reflected on one of the Beatitudes from Jesus’s sermon in Matthew 5. Navalny admitted that hungering and thirsting for righteousness may seem “esoteric and odd” to people today. Adding a reference to the Harry Potter books, he explained how the Beatitude gave him hope even in a nation ruled by “our own You-Know-Who in his palace.”

“I’ve always thought that this particular commandment is more or less an instruction to activity,” Navalny said. “Without question, this whole biblical passage — ‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be satisfied’ — comes across as overly theatrical to modern ears. It is assumed that people who say such things are crazy. … This is the key point. Our authorities and the system as a whole try to tell these people that they are pathetic loners.”

“We see that millions or tens of millions of people want the truth. They want to get to the truth, and sooner or later they will do so. They will be satisfied,” he added. “Because it is obvious to everyone — a palace exists. You can say that it does not belong to you or that it does not exist, but it surely does. And we also see the poverty. You can say as much as you like that we have a high standard of living, but the country is poor and this is obvious to everyone. … This is the truth, and you can’t argue against it. And sooner or later these people who want the truth will get their due and be satisfied.”

Like most dreamers and prophets, Navalny won’t live to see that day. But he believed it would come. Others joined him in that dream after his assassination. And in doing so, they showed the prophetic power of another Beatitude: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

Following news of Navalny’s death, hundreds of Russians created ad-hoc memorials in more than three dozen cities. In many places they started laying flowers at memorials to victims of Soviet Gulag camps — thus not only honoring Navalny but also comparing Putin to the murderous dictator Joseph Stalin.

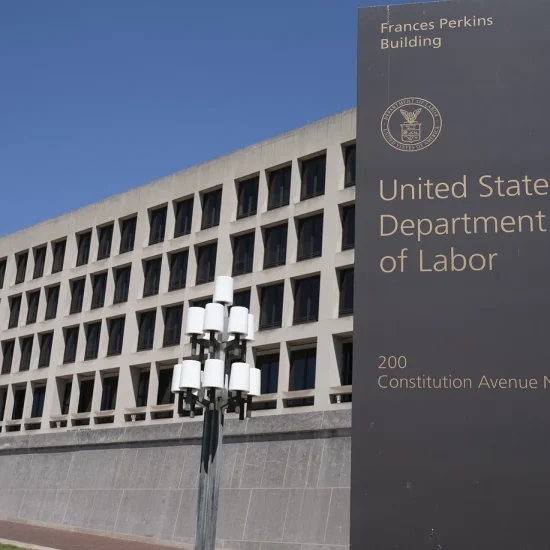

A police officer watches as a man lays flowers to honor Alexei Navalny at a monument featuring a large boulder from the Solovetsky islands (where the first camp of the Gulag political prison system was established), in St. Petersburg, Russia, on Feb. 17, 2024. (Dmitri Lovetsky/Associated Press)

Among those detained since Navalny’s death was a priest in an Orthodox church not affiliated with the Putin-aligned Russian Orthodox Church. His “crime” was announcing he would hold a memorial service for Navalny, and the priest was later hospitalized after authorities claimed he suffered a stroke.

Those detained for mournfully placing flowers are being sentenced to up to 14 days in prison. Simply for daring to grieve in public. But this isn’t the first time an authoritarian regime sought to stop those who mourn. So this issue of A Public Witness explores the subversive power of public mourning to better understand a Beatitude of Jesus.

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.