ROANOKE RAPIDS, N.C. (ABP) — Tensed like a hungry cat watching a mouse emerge from a hole in the floor I watched the string of numbers on my lottery ticket as Anna Anderson read aloud numbers on the ticket she had just drawn at the front of the room.

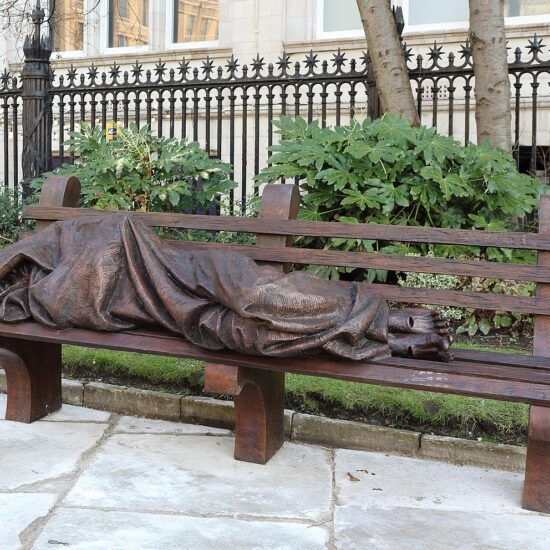

Kim Walker, left, and Amy Day sort through the Union Rescue Mission of Roanoke Rapids clothes closet to find their clothes for the 24-hour poverty plunge.

|

Two "winners" would be designated "homeless" for the rest of our 24 hours as participants in a poverty plunge in Roanoke Rapids, N.C. The "homeless persons" would be able to keep not even the three personal items the rest were allowed and would forfeit the $30 in play money we were counting on to buy a place to sleep inside that night and a single meal.

Please, Lord, don't let me win.

My clenched stomach relaxed when winning numbers did not match my ticket and I knew I could keep my sleeping bag, pad and jacket; could sleep inside and buy dinner at the rescue mission. I felt a winner by losing.

The "winners?" They actually were excited to know they would experience this 24-hours as close to the street as possible after dropping out of their middle class insulation and stepping into the bare, cold room of poverty and homelessness.

This poverty plunge was sponsored by the North Carolina Woman's Missionary Union in partnership with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship's transformational development missionary LaCount Anderson.

A CBF missionary who raises his own support, Anderson directs the Union Rescue Mission of Roanoke Rapids, which was started 60 years ago by a Sunday School class out of First Baptist Church in town. Anderson's wife, Anna, is similarly self-supported and on staff at Rosemary Baptist Church, which hosted the poverty plunge participants.

Together the Andersons guided nine participants and a WMU leader through the weekend. LaCount often responded to questions such as "Where would 'outside' be if we have to sleep outside?" and "Why do you give a box of free food to someone driving a Mercedes?" by saying, "That's a middle class question," suggesting that our only purpose is to serve.

When it came time to lock my identity in a drawer — my cell phone, watch, wallet — and walk out the door into a world where no one knows my name or cares where I came from I felt exposed, naked and vulnerable.

At the same time, I felt transparent. I left the baggage of personal history behind and to anyone I met I was no more and no less than simply the package of self I presented at that moment.

We traded nine precious dollars for dinner and a shirt and pants we selected from the rescue mission's clothes closet. LaCount wanted us to lose the clothing veneer that set us apart from the poor. I actually upgraded my apparel, trading my jeans for some Land's End wool slacks with the tag still on them, and a striped dress shirt for my old pullover.

A jarring moment of reality vibrated against my artificial submersion when I went to "pay" for the clothes with a voucher I'd received from a rescue mission worker who screened me. When I laid the paper on the counter, rather than money, I felt awkward, even ashamed. LaCount said the poor are used to finding means other than money to get by and are not uncomfortable when using a voucher.

Tellingly, when LaCount saw me in my new duds, he asked if I had changed clothes and then said, "I can't ever tell." Quality clothes in the closet helps the poor dress with dignity and my outfit would have cost just $7. We gave the clothes back the next day, but I bought my shirt!

We spent the afternoon and next morning packing 250 boxes with about 40 pounds of food given and purchased from the Central and Eastern North Carolina Food Bank in Raleigh. They would be distributed to persons who lined up long before the mission opened. Some of the food was great — pork tenderloin and salad material and vegetables. Some had little nutritional value but would be tasty and effective in stilling hunger pains for a few hours.

We ate dinner with the six current residents of the mission, then heard their stories and asked questions, trying to comprehend how people "end up" in such situations. It was hard for middle class participants to hear how poor families simply had no ability to feed another mouth.

Walking the half-mile back to the church from the rescue mission, the chill night air penetrating our second-hand clothes, we discussed the men we'd met; how easily most of them shared and how they seemed safe, secure and peaceful in the face of their traumatic life experiences.

And we wondered just how tightly the blanket of cold night air would wrap around us in whatever cranny we found to lay outside, in unity with the designated homeless in our group. Back at the church Anna told us that safety concerns prompted WMU leadership to keep everyone in the building and "outside" for us would be sleeping in the unheated stairwells.

Participants expressed no disappointment. Being middle class does have its perks, and the ability to self-determine a place to lay our heads is high on the list.

Norman Jameson is reporting and coordinating special projects for ABP on an interim basis. He is former editor of the North Carolina Biblical Recorder.