It’s that time of the year when hell is used as a common theme for entertainment and hell-themed haunted houses and horror movies pop up all over the country.

What was behind early depictions of hell? Photo by Erica Zabowski/Creative CommonsAlthough many of us now associate hell with Christianity, the idea of an afterlife existed much earlier. Greeks and Romans, for example, used the concept of Hades, an underworld where the dead lived, both as a way of understanding death and as a moral tool.

What was behind early depictions of hell? Photo by Erica Zabowski/Creative CommonsAlthough many of us now associate hell with Christianity, the idea of an afterlife existed much earlier. Greeks and Romans, for example, used the concept of Hades, an underworld where the dead lived, both as a way of understanding death and as a moral tool.

However, in the present times, the use of this rhetoric has radically changed.

Rhetoric in ancient Greece and Rome

The earliest Greek and Roman depictions of Hades in the epics did not focus on punishment, but described a dark shadowy place of dead people.

In Book 11 of the Greek epic the “Odyssey,” Odysseus travels to the realm of the dead, encountering countless familiar faces, including his own mother.

Near the end of Odysseus’ tour, he encounters a few souls being punished for their misdeeds, including Tantalus, who was sentenced eternally to have food and drink just out of reach. It is this punishment from which the word “tantalize” originated.

Hundreds of years later, the Roman poet Virgil, in his epic poem “Aeneid,” describes a similar journey of a Trojan, Aeneas, to an underworld, where many individuals receive rewards and punishments.

This ancient curriculum was used for teaching everything from politics to economics to virtue, to students across the Roman empire, for hundreds of years.

In later literature, these early traditions around punishment persuaded readers to behave ethically in life so that they could avoid punishment after death. For example, Plato describes the journey of a man named Er, who watches as souls ascend to a place of reward, and descend to a place of punishment. Lucian, an ancient second century A.D. satirist takes this one step further in depicting Hades as a place where the rich turned into donkeys and had to bear the burdens of the poor on their backs for 250 years.

For Lucian this comedic depiction of the rich in hell was a way to critique excess and economic inequality in his own world.

Early Christians

By the time the New Testament gospels were written in the first century A.D., Jews and early Christians were moving away from the idea that all of the dead go to the same place.

Early Christians portrayed hell through different terms. Here is “The Harrowing of Hell,” an old Icon painting. Image courtesy of Creative CommonsIn the Gospel of Matthew, the story of Jesus is told with frequent mentions of “the outer darkness where there is weeping and gnashing of teeth.” As I describe in my book, many of the images of judgment and punishment that Matthew uses represent the early development of a Christian notion of hell.

Early Christians portrayed hell through different terms. Here is “The Harrowing of Hell,” an old Icon painting. Image courtesy of Creative CommonsIn the Gospel of Matthew, the story of Jesus is told with frequent mentions of “the outer darkness where there is weeping and gnashing of teeth.” As I describe in my book, many of the images of judgment and punishment that Matthew uses represent the early development of a Christian notion of hell.

The Gospel of Luke does not discuss final judgment as frequently, but it does contain a memorable representation of hell. The Gospel describes Lazarus, a poor man who had lived his life hungry and covered with sores, at the gate of a rich man, who disregards his pleas. After death, however, the poor man is taken to heaven. Meanwhile, it is the turn of the rich man to be in agony as he suffers in the flames of hell and cries out for Lazarus to give him some water.

For the marginalized other

Matthew and Luke are not simply offering audiences a fright fest. Like Plato and later Lucian, these New Testament authors recognized that images of damnation would capture the attention of their audience and persuade them to behave according to the ethical norms of each gospel.

Later Christian reflections on hell picked up and expanded this emphasis. Examples can be seen in the later apocalypses of Peter and Paul – stories that use strange imagery to depict future times and otherworldly spaces. These apocalypses included punishments for those who did not prepare meals for others, care for the poor or care for the widows in their midst.

Although these stories about hell were not ultimately included in the Bible, they were extremely popular in the ancient church, and were used regularly in worship.

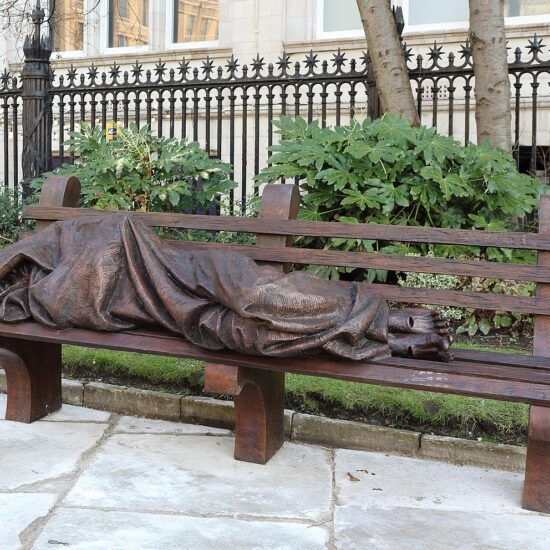

A major idea in Matthew was that love for one’s neighbor was central to following Jesus. Later depictions of hell built upon this emphasis, inspiring people to care for the “least of these” in their community.

Damnation then and now

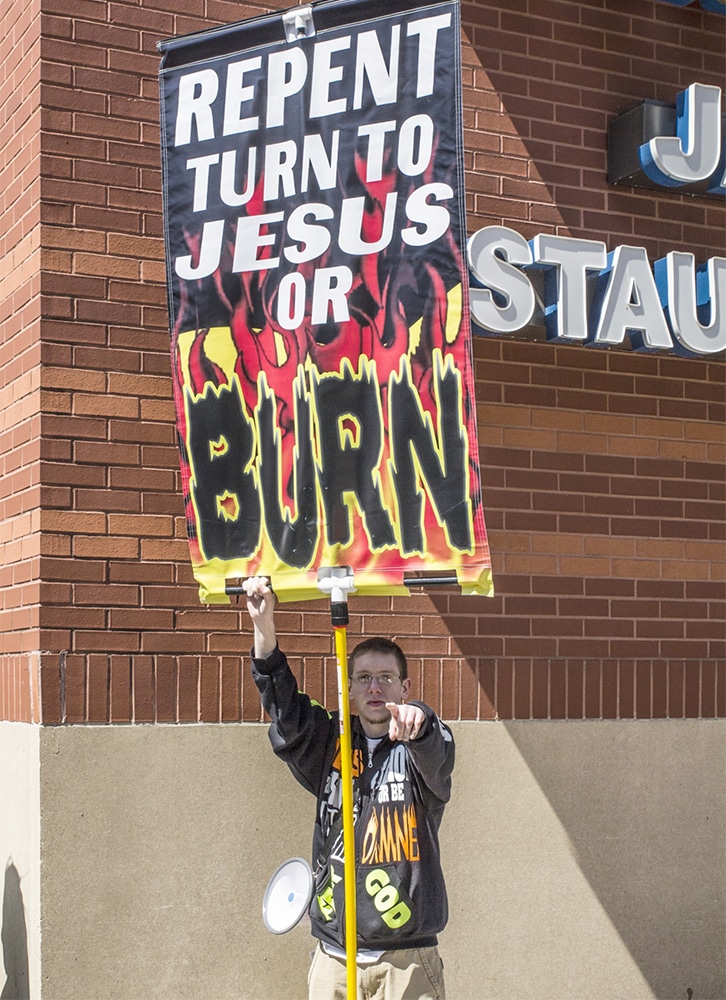

The idea of hell is used to bring about conversions. Photo by William Morris/Creative CommonsIn the contemporary world, the notion of hell is used to scare people into becoming Christians, with an emphasis on personal sins rather than a failure to care for the poor or hungry.

The idea of hell is used to bring about conversions. Photo by William Morris/Creative CommonsIn the contemporary world, the notion of hell is used to scare people into becoming Christians, with an emphasis on personal sins rather than a failure to care for the poor or hungry.

In the United States, as religion scholar Katherine Gin Lum has argued, the threat of hell was a powerful tool in the age of nation-building. In the early Republic, as she explains, “fear of the sovereign could be replaced by fear of God.”

As the ideology of republicanism developed, with its emphasis on individual rights and political choice, the way that the rhetoric of hell worked also shifted. Instead of motivating people to choose behaviors that promoted social cohesion, hell was used by evangelical preachers to get individuals to repent for their sins.

Even though people still read Matthew and Luke, it is this individualistic emphasis, I argue, that continues to inform our modern understanding of hell. It is evident in the hell-themed Halloween attractions with their focus on gore and personal shortcomings.

These depictions are unlikely to portray the consequences for people who have neglected to feed the hungry, give water to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, cloth the naked, care for the sick or visit those in prison.

The fears around hell, in the current times, play only on the ancient rhetoric of eternal punishment.

Meghan Henning is an assistant professor of Christian Origins at the University of Dayton. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.