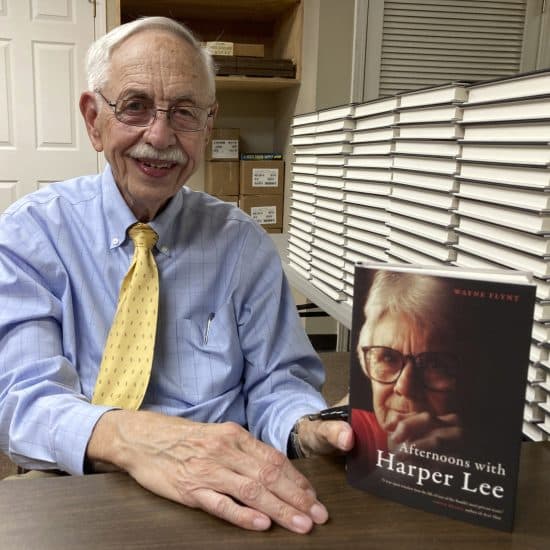

Biblical scholar Peter Enns. Photo credit: Shelby Kuchenbrod.

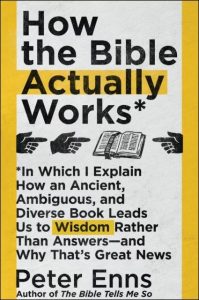

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The Bible isn’t a rule book, an instruction manual, or a road map, says Peter Enns, a Hebrew Bible scholar and the host of the popular podcast The Bible for Normal People.

So what is it?

Something more complicated but infinitely better, as he explains in his thought-provoking new book How the Bible Actually Works: In Which I Explain How an Ancient, Ambiguous, and Diverse Book Leads Us to Wisdom Rather Than Answers—and Why That’s Great News, a book I thought was fascinating (not to mention quite funny) — JKR

RNS: I loved this book, which seems to be about the importance of honest wrestling with the Bible. You focus here on the Bible as a model of situational wisdom: what it teaches is not always consistent from one situation to another, and our job is to figure out how to navigate that.

Enns: In this book I take a more constructive approach than in my other books, which focused on deconstructing some points of view about the Bible that are very problematic. I’m trying show what the Bible’s antiquity, ambiguity, and diversity tell us positively how the life of faith is more like a quest for wisdom than following a road map or book of instructions.

The Bible doesn’t work well as an owner’s manual that lays out for us what to do or think at every turn. It is holding out to us the invitation to accept the sacred responsibility going forward and working things out.

RNS: Early in the book you look at an example of how the laws about slavery change from one part of the Torah/Pentateuch to another. Slavery was a given in that world, but the specifics changed quite a lot.

Enns: Torah has diversity in its laws, and that’s been a fact of life for people of faith from the beginning, so we shouldn’t be surprised when we run into them. One example concerns Hebrew slaves. In Exodus, a male Hebrew slave, if he wishes to, can go free in the seventh year. Hebrew slaves who are women, however, are not given the option of going free.

In Deuteronomy, which clearly mirrors this law in Exodus, both male and female Hebrew slaves have the option to go free in the seventh year. One way to explain this change in this later version of the law is that Israelites thought it more consistent with God’s nature. But whatever the reason, it is clearly different and more humane. Leviticus contains probably the most recent version of the law, and now no Hebrew slaves are allowed at all. They can work for you for hire, and you can own non-Hebrew slaves, but you can’t own Hebrew slaves.

RNS: You say that this kind of contradiction is not a mistake but a model: the Bible itself is modeling for us how people need to reinterpret the law with every passing generation in a changing society.

RNS: You say that this kind of contradiction is not a mistake but a model: the Bible itself is modeling for us how people need to reinterpret the law with every passing generation in a changing society.

Enns: Right. These changes in laws—all believed to have been given by God on Mt. Sinai, mind you—demonstrate that obeying God isn’t simply a matter of “obeying the law” but of thinking through what it means to obey God as circumstances change. More than simply being about changing views on slavery, we are seeing here different ways of thinking about what God is like, and what God expects from us in treating others.

These laws are not meant to be awkwardly reconciled, as if deep down they are actually saying the same thing, but respected as telling us something about how the Bible works. These laws contradict, and saying so is not an attack on the Bible but an acknowledgment of what is there. These contradictions are characteristics I embrace, and I actually think they are what make the Bible worth reading because they push us to think for ourselves, “Okay, what does it mean to obey God here and now?”

RNS: Is that idea threatening for conservative Christians? That the contradictions in the Bible are a feature, not a bug?

Enns: It is, and I get it. Many Christians are taught to think from the outset, before they really have a chance to read the Bible carefully as adults, that the Bible by definition cannot contain contradictions. That is a hard position to maintain even within the first five books of the Bible. Rather than avoid the contradictions or explain them away, we should listen to what they are telling us.

RNS: You spend a lot of the book trying to help readers understand historical context, especially that our understanding of God is conditioned by our time and place. In the Old Testament, for example, they took it for granted that of course other gods really existed.

Enns: In the second half of the book I use the language of “imagining” and “reimagining” God. All of our God-talk, all of our conceptions of God, are inevitably filtered through our humanity—and that is no less true of the biblical writers.

For instance, in 2 Kings 3 we meet King Mesha who ruled Moab in the ninth century, which borders Israel across the Jordan river. Moab has been subject to Israelite rule, and Mesha decides to rebel, prompting the king of Israel Jehoram to put Mesha in his place. So Mesha is outnumbered, and in an act of desperation, he sacrifices his own son on the city wall.

What many of us might expect the Bible to do with this story is to show that the child sacrifice doesn’t work because that other god doesn’t exist (and because child sacrifice is wrong and barbaric). But that’s not what happens. The story ends, “And a great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from [Mesha] and returned to their own land” (v. 27). In other words, it worked.

I like using the word “imagination” with God. We all image God in our minds in ways that make sense to us culturally, and the Bible itself models that. In the Bible YHWH is not the only God in existence; he’s one of many, but what makes him worthy of worship is that he’s the best one. In the Exodus plague narratives Yahweh does battle with the gods of Egypt (see Exodus 12:12). Psalm 95 claims that Yahweh is the “great king above all gods.” These stories show us that people will articulate God in ways that make sense to them culturally. And back in the day, it was that there were lots of gods, and they were being worshiped all over the place.

I don’t personally believe that many gods exist. But that’s irrelevant because the Israelites clearly did. Judaism and Christianity are now monotheistic religions, but they didn’t start out that way. Jews and Christians have reimagined God, and we see that process happening in the Bible itself.

RNS: You said that people will articulate God through the lens of what makes sense to them culturally. How are we articulating God in America today, based on our culture? In what ways does that reflect—or not reflect—the Bible?

Enns: A common and true criticism of conservative Christianity in America is that we’ve forgotten the prophetic call, in both Testaments, to call power to account rather than align the Gospel with any political regime.

This is a place where Americans have a deaf ear to the way the biblical tradition has already reimagined something that is very important, something that sticks. The non-alignment of the kingdom of heaven with empire is a vital message we should be sending. The role of people who try to follow Jesus, and who follow the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament, is to critique power, not to seek after it.

RNS: Is there anything else you want readers to know about How the Bible Actually Works?

Enns: I would just want to stress that the punch line of the book is that the Bible is designed for us to seek wisdom, and to ask ourselves what this faith we are a part of requires of us in this moment. The answers to those questions are rarely simply written out for us. And we are all in the same boat on that. I think that’s actually what God wants: to raise us to be thoughtful, mature followers rather than young children always looking for a parent to tell them what to do. The Bible, simply by being what it is, points—or even pushes—us in that direction. And that is good news.