Characters Harry, left, Ron and Hermione in a scene from the Harry Potter film series. Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

(RNS) — It’s a book nearly everybody knows, many of us nearly from birth. We reference it in our daily lives. We use its complicated moral systems to define our social and political stances and to understand ourselves better. Once we have read it, and learn the lessons considered therein, our political attitudes alter, making us more welcoming and more caring to outsiders.

Activists quote from the stories on placards to make their points at protests. Hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of people have written their own narratives in response to these foundational myths.

I refer, of course, to the “Harry Potter” series.

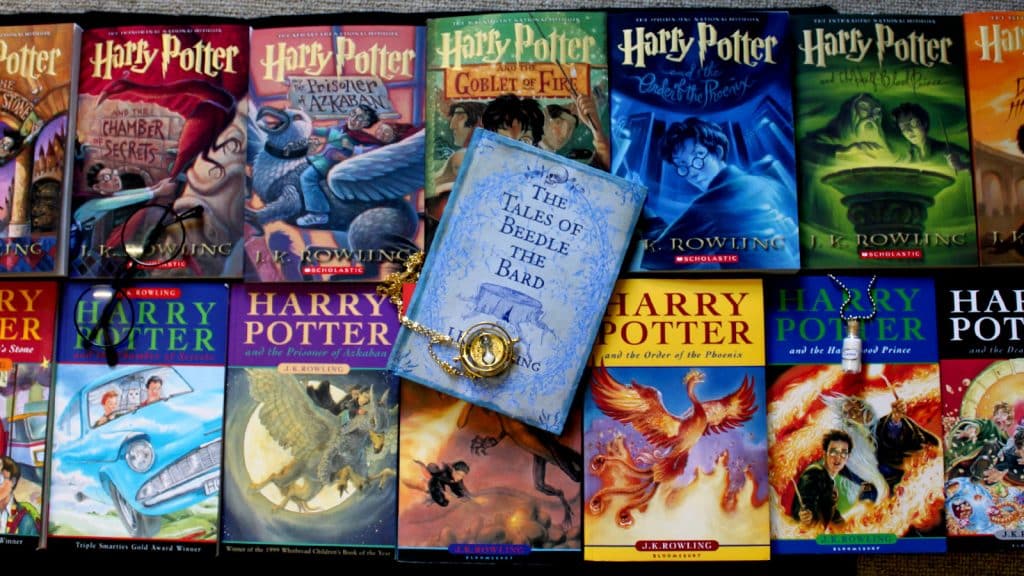

It may seem flippant to talk about J.K. Rowling’s behemoth young adult fantasy series as a foundational myth that threatens, at least among millennials and Gen Z, to replace the Bible. But the numbers bear out its place as mythical bedrock. Sixty-one percent of Americans have seen at least one “Harry Potter” film. Given that just 45% of us (and a barely higher 50% of American Christians) can name all four Gospels, it’s no stretch to say that Gryffindor, Slytherin, Ravenclaw and Hufflepuff are better known in American society than Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

American and British versions of the Harry Potter book series. Photo by Lozikiki/Creative Commons

For politically progressive millennials in particular, “Harry Potter” is more than a book series. It’s an entire theology. While they rarely deal with questions of God explicitly, or propose a metaphysical theology per se, their explorations of good and evil are nothing if not cosmic.

And when it comes to millennial religious “nones,” its moral teachings are certainly no less known or espoused than the Good Book’s. Rowling’s narrative is the story of the redemption of perceived outsiders — the children of mixed Muggle-human families — from the vengeance of the wizarding elites, who slur the Muggle-born as “mudbloods.” House elves, a species consigned to servitude, reveal their dignity through their bravery.

Numerous studies have tracked a direct correlation between a budding political liberalism — particularly pro-immigrant stances — and the “Potter” books. Controlled studies show that reading passages from the books altered children’s views of strangers.

Nor is Rowling’s message of tolerance the only way in which we overlay the moral and ethical systems of Harry Potter over our own world. Our enemies are Voldemorts or his followers, such as the repressive and sadistic Hogwarts teacher Dolores Umbridge. Never mind “Onward, Christian Soldiers”; we attend rallies on the most serious, and sacred, issues as “Dumbledore’s army.”

“If HOGWARTS students can defeat the DEATHEATERS, then U.S. STUDENTS can defeat the NRA,” read one sign on the National Mall last March at the March for Our Lives, organized by survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shootings in Parkland, Fla. Another read: “Dumbledore’s Army: still recruiting.”

The difference, of course, is that “Harry Potter” makes no ontological truth claims. It advertises itself clearly as a work of fiction. Yet, for many nominal Christians as well as for the religiously unaffiliated, it functions as a paramount sacred text.

Harry Potter and Albus Dumbledore in the Harry Potter film series. Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

“Harry Potter” isn’t the only 20th-century cultural property to have doubled as a quasi-religion. As early as the 1970s, “Star Trek” – among the first “fandoms” in history – offered its devoted fans a vision of morality and the human condition rooted in the humanist, positivist secularism of its creator, Gene Roddenberry.

Likewise, in the 1990s hundreds of thousands of nones identified themselves as Jedi, the priestly class of space samurai in the “Star Wars” movies, on national censuses in the U.K., Wales and Australia.

But “Harry Potter” has garnered cultural capital on a far grander scale, due in no small part to the advent of the internet.

Between the publication of the first “Harry Potter” book and the fourth in the installment, the number of Americans who used the internet increased by 500%. Internet fan culture, at the same time, went from being the province of coders and technologically proficient insiders to include the average, often adolescent, fan consumer.

It’s in this intertwined history that “Harry Potter” most resembles the Bible. Scholars have long argued that the rise of Protestantism and that of the printing press were inextricably meshed, as Martin Luther’s tracts testifying to the power of personal faith fed a new means of distribution. The Reformation, in other words, thrived on the symbiosis between the ferocious demand for Luther’s controversial tracts and the new printing technology.

Harry Potter, left, and Voldemort battle in a scene from the film “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2.” Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

The rise of “Harry Potter” and modern internet culture is no less intertwined. The popular engagement with the “Potter” texts online brought millions to the World Wide Web, which in turn has indelibly shaped, and remixed, our approach to self and belief.

A cosmic-level foundational story, disseminated through a new medium that celebrates not just personal experience but the reimagining and responding to (and, through the rise of fanfiction, even rewriting) “Harry Potter” grounds many millennial nones’ moral, political and ethical systems.

The fact that the “Potter” series does not pretend to be anything more than fiction says a lot about what we require from our foundational texts. We buy Rowling’s language, her moral systems and her emotional tenor without needing — or wanting — it to make referential claims about the world, or God, out there.

This reflects broader trends among religiously unaffiliated Americans and among American Christians, a record low number of whom — just 30% — now see the Bible as the literal word of God. Another 14% frankly call it fables.

Fewer and fewer of us need to believe in a text in order to take it, well, as gospel.