The Museum of the Bible main entrance in Washington, D.C. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

(RNS) — To say that biblical scholars have been critical of the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., is an understatement.

Since it opened in late 2017, the pet project of Oklahoma billionaire and outspoken evangelical Steve Green, CEO of Hobby Lobby, has been accused of privileging the Protestant Bible over other versions, harboring questionable and misappropriated antiquities among its vast collection and partnering with a range of charismatic, Pentecostal and conservative Christian groups, including the Creation Museum and Ark Encounter, in ways that suggest it wants to advance an evangelical agenda.

Last year alone, the museum acknowledged that five Dead Sea Scroll fragments it had on display were forgeries and returned a medieval New Testament manuscript to the University of Athens after learning the document had been stolen.

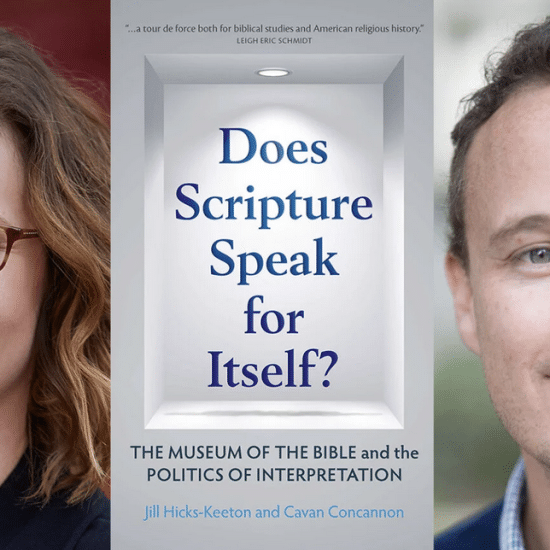

Now many of the academic community’s critiques have been collected in a book, edited by Jill Hicks-Keeton, assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Oklahoma, and Cavan Concannon, associate professor of religion at the University of Southern California.

“The Museum of the Bible: A Critical Introduction” Edited by Jill Hicks-Keeton and Cavan Concannon

Religion News Service spoke to Hicks-Keeton about the book, published last month by Lexington Books. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

At what point did you realize you wanted to put together this book?

It began when I organized a panel discussion at the Association for Jewish Studies in Washington in 2017 on how Jews, Judaism and the Jewish Bible are represented in the museum. Later, an editor reached out to me to see if I’d be interested in doing a collection of essays on supersessionismn (the belief that Christianity has superseded or replaced Judaism), but as the volume evolved and my collaborator, Cavan Concannon, signed on, it became clear what we were really interested in was collecting a variety of voices of biblical scholars and those in related disciplines about the museum.

Who is your intended audience?

Anyone interested in the Bible, how the Bible is represented in the public sphere or evangelical interpretations of the Bible. Or anyone who wants a professional scholar’s unauthorized guidebook to the museum.

Why does this museum demand so much attention?

Part of the reason is the money invested in it. It’s in a very public place, near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. One might even think, mistakenly, that it’s a Smithsonian. This museum is poised to have some influence on the way that the public understands the Bible. Our job as educators in the field of biblical studies is to use the museum as an opportunity to teach a wider public about the academic study of the Bible and its history.

What are some of the major criticisms of the scholars?

If one were to read all essays, they make a case that the museum is deeply intertwined with the evangelicalism of the founding Green family. Many people say it’s not a problem for people to use private money to invest in something they think is important, (but) we bristle at the public representation of their project. They say they have no perspective and no agenda. We don’t think that’s possible or true.

Are scholars saying the museum should come out and say what its perspective is?

That’s one way to rectify what they think is wrong. But the volume is not written for the museum. Our job as scholars is to analyze and catalog and chronicle what’s happening with how the Bible is represented. If the museum leadership doesn’t make changes as a result of the book, we won’t feel like the book has failed. It’s written for a wider audience and not in order to change the museum.

Give me a few examples of the criticisms of the museum in the book.

Jill Hicks-Keeton. Photo by Travis Caperton

One section is on how the Bible is defined and framed in the museum. There’s a chapter by Margaret M. Mitchell (University of Chicago) on the museum’s Bible boosterism, arguing that the museum is creating Bible boosters rather than critical thinkers about the Bible.

Another major critique of the exhibits is that the Protestant Bible, and specifically the white evangelical Protestant Bible, gets prioritized to the exclusion of other people and traditions for whom the Bible is important. Duke Professor Marc Brettler and I each have chapters arguing the Jewish Bible is really not represented accurately in this museum.

One other chapter is how archaeology is represented in the museum and the land of Israel. Cavan Concannon argues that archaeology gets leveraged to support ideas about the Bible that aren’t historically sustainable. For example, the idea that the Bible was transmitted through time perfectly, which is demonstrably untrue from a historical standpoint. Another chapter is about the history of the Green family’s foibles in the illegal collection of antiquities processes and a call for there to be more transparency in the acquisition process and how these objects are displayed.

The museum has evolved since it opened. Are most of the critiques current?

All the essays dependent on visits to the museum have the dates of the authors’ last visit. The last time I visited was in February. The essays are up to date as far as we know. If the museum made changes we hope the book will still be relevant because it’s important to document the origins of the museum and its changes over time.

What changes have you noticed since you’ve been going?

One change involves a set of purple banners on the history floor that were part of a Christian theological project in interpreting the Bible. The most problematic one had a quotation from the New Testament referring to prophecy hanging by the Torah scroll exhibit. A visitor who didn’t know any better would think the word prophecy was being applied to Torah scrolls, and they might think the Torah anticipated the New Testament. Making the New Testament seem like a natural part of the Bible is a Christian view of the Bible.

After speaking to me, the CEO of the museum had a banner taken down and mailed it to me. We wrote them back to say that this was great they took down a problematic banner but the museum needed to educate the public about why it took it down. We urged them to take down the other purple banners. It seemed the change they made was an attempt to silence their critics, rather than to institute change.

Would you say most Bible scholars at secular universities are critical of the Museum of the Bible?

The scholars I know are critical. But by definition, we’re supposed to be critical. One of the critiques biblical scholars have is that they would prefer it if the museum just stated what its position is — that it’s an evangelical Christian project. But there are some biblical scholars who are consultants for the museum and they want to change it from the inside. If they critiqued the museum publicly, they’d lose access. To my mind, that means they implicitly agree the museum needs changing. They have a different mechanism for working toward that.

You teach at the University of Oklahoma. Is there a special attitude toward the Greens in Oklahoma?

Steve Green, co-founder of the Museum of the Bible, speaks at the dedication ceremony for it in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 17, 2017. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

My connection to them is through my students. A lot of my students either go to church with them or know them because they’re so influential here. They’re regarded among evangelical Christians here as heroes because of their work in promoting the Bible. The coverage of the museum in the Oklahoma press has been consistently positive. The son-in-law of Steve Green, Michael McAfee, is a teaching pastor at their church and also director of community initiatives at the Museum of the Bible.

The museum has tried to be more inclusive of late. They recently had an exhibit on the slave Bible used during the Colonial period, for example. Does that help?

If they are wanting to be what they say they are, which is diverse and inclusive, then the permanent exhibits need to be overhauled. Adding temporary exhibits is like putting icing on a cake. It’s not going to solve the problem.