Jeremy Everett is founding executive director of the Texas Hunger Initiative at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. (Baylor University Photo)

WACO—Jeremy Everett believes a divided nation can find common ground in a battle to eliminate chronic hunger.

“It is possible to build bipartisan consensus around the issue of hunger. In fact, I don’t think we have a choice. It will be catastrophic otherwise. Our nation will fall apart if we don’t find a way to pull together,” said Everett, founding executive director of the Texas Hunger Initiative at Baylor University. in Waco.

Chronic Hunger Can Be Eliminated

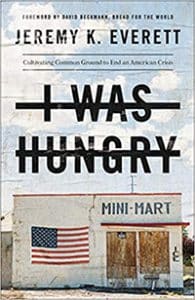

Everett, author of I Was Hungry: Cultivating Common Ground to End an American Crisis, views hunger as a large and complex problem no single group acting alone can solve. However, he believes persistent hunger can be eradicated when Americans work together across political party lines.

“I’m optimistic we can end hunger,” he said. “Hunger will always be an issue when there is war or natural disaster that sets a country or a region back temporarily. But it’s not something we have to live with. We can ensure that people have adequate access to food.”

Five years ago, the United Nations reported the number of hungry people globally had declined by more than 100 million in the previous decade and more than 200 million since the early 1990s.

Everett also has seen improvement on a local and regional scale, both through his work at the Texas Hunger Initiative and during his years as a community organizer.

‘Broken Streetlight’

‘Broken Streetlight’

In that latter role, working in San Antonio’s West Side about 15 years ago, he observed personally what social workers and community developers call the “broken streetlight theory.”

The idea is based on a scenario in which a community developer needs to earn the trust of a neighborhood by identifying a shared concern that is “winnable,” he explained. Rampant underemployment, substandard schools and lack of access to health care may be commonly identified problems, but they are too complex and large to tackle initially.

However, if the people in the neighborhood mention a broken streetlight on a corner that provides easy cover for drug dealers and makes local residents feel unsafe, that offers a problem that can be addressed.

Once the streetlight is repaired, drug dealers move away, and children feel safe playing in their front yards. In the process, the community feels empowered.

Everett sees hunger as the “broken streetlight” of American politics.

“Hunger is something we can solve,” he said. “Poverty can be a more contentious issue. But if we take on hunger first, it’s possible to build consensus and coalitions that can address other underlying problems that contribute to hunger.”

Common Ground and Common Good

People of good will may differ on many policies, but they agree people should not go hungry, Everett said.

“We can find common ground by working for the common good,” he said.

Consensus can be found most readily at the grassroots level, he observed.

“Partisanship is less of an issue when building local coalitions,” he noted, pointing to the network of hunger-free community coalitions the Texas Hunger Initiative has helped create across the state.

Jeremy Everett was appointed by the U.S. Congress to serve on the bipartisan National Commission on Hunger. (Baylor University)

However, it also is possible nationally, said Everett, who was appointed by the U.S. Congress to serve on the bipartisan National Commission on Hunger.

Initially, the 10 members of the commission—five appointed by Democrats and five named by Republicans—made little progress, he observed.

But as they developed personal relationships with each other and met people in the United States who were experiencing hunger, they began looking for ways to work together, he noted.

Not Optional for Christians

People of faith—particularly Christians—may propose different political solutions to address the problem of hunger, he said. But they share a common commitment to caring for people in need, he insisted.

While segments of society may scapegoat and dehumanize the poor as lazy and undeserving, Christians recognize every person as bearing the image of God, Everett said. In fact, Matthew 25 teaches Jesus particularly identifies with the hungry and the poor. How professing Christians respond to hungry people reveals how they respond to Jesus, he asserted.

“A core component of God’s judgment is how we treat the hungry. It’s not an extra credit assignment,” Everett said. “If we really are all in for Jesus, this is what it means to be all in for Jesus.”

This article was originally published by the Baptist Standard and is used by permission.

‘Broken Streetlight’

‘Broken Streetlight’