RALEIGH, N.C. (RNS) — A dozen red roses in their clear cellophane wrapper were perched in a glass vase on Shannon Dingle’s kitchen counter, an indulgence she bought for herself earlier in the week as a way of coping with the grief for her husband, Lee, who used to buy them for her.

Life is still unbearably painful, nearly two years after Lee’s sudden death. On July 18, 2019, a powerful ocean wave knocked the 37-year-old father of six to the ground, breaking his neck. Shannon, a writer, sex abuse survivor, disability activist, and Christian influencer, is picking up the pieces. Her book Living Brave: Lessons From Hurt, Lighting the Way to Hope published this week.

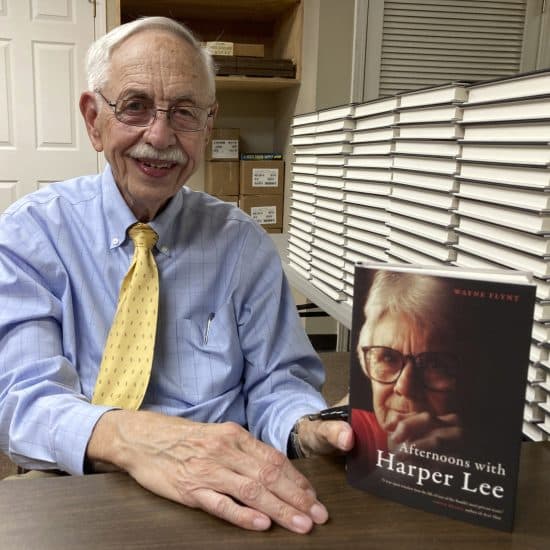

Shannon Dingle in her home. (Yonat Shimron/Religion News Service)

A powerful blend of memoir and self-help, the book offers raw testimony to the lessons she has gleaned trying to survive the loss. Dingle knows grief is not something that ends after a prescribed amount of time.

“There are lots of books that will tell you how to get over it,” she said. “They’re all bullshit.”

Her book offers a more clear-eyed account of what it takes to try to move forward. One key: self-compassion. June was hard enough. Dingle marked her 39th birthday, her wedding anniversary, and Father’s Day. Now it’s July. In a few days, she will mark the two-year anniversary of Lee’s death. Getting through these occasions requires a strategy. Hence the roses. Remembering how Lee loved and cared for her — and giving herself permission to love and care for herself — helps steel her for the hard days.

The title, Living Brave, rather than the more conventional, “living bravely,” is intentional. “No ‘ly,’” she writes in her book, “because no Lee.”

In it, she writes about leaning into grief, allowing herself to dwell in discomfort, accepting uncertainty, connecting to feelings, expressing hard truths, getting psychological help. Her hope is that the book might give readers permission to grieve more openly and honestly.

“Being comfortable in your story and not tidying it up for people, that ends up letting other people feel they can do the same,” she said.

Along the way, she offers snippets of her life story, the broad contours of which she has shared in newspaper articles and with her large social media following.

Dingle acknowledges from the get-go, this is not the book she had intended to write. She had been under contract for another book, in which she intended to share the harrowing experience of growing up in a suburb of Tampa, Florida, where she was repeatedly raped by her father and others who trafficked her body for sexual pleasure. (Her father died in 2018.)

Somehow, she still excelled in school, won a scholarship to the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, and through a campus ministry met the love of her life: a young civil engineering student named Lee Dingle. The couple married young, joined a Southern Baptist church, had two biological children, and went on to adopt four more.

Dingle, who suffers from several autoimmune diseases and has undergone numerous knee and spine surgeries, was drawn to disability issues. One of her daughters has cerebral palsy and uses a motorized wheelchair. A son has autism, another is HIV-positive. Working on disability issues seemed like a calling.

At Providence Baptist Church, a congregation favored by Raleigh’s religiously conservative establishment (Anne Graham Lotz was once a member), she led the disability ministry. But the more Dingle underwent therapy to examine her childhood trauma the less she felt she and her family fit there.

“I really liked clear rules and black and white and right and wrong,” she said. “Now I know that’s a symptom of PTSD. There’s no room for both/and.”

A couple of events contributed to her growing disenchantment. Unlike her church, she found herself opposed to the passage of a now repealed 2016 North Carolina statute that prohibited transgender people from using public bathrooms that align with their gender identity — the so-called bathroom bill. As that year’s presidential election cycle unfolded she also felt increasingly at odds with most white evangelicals. Shortly after leaving the church, she wrote about why she, a Christian who opposes abortion, was voting for Hillary Clinton.

The Dingles found a new church, a United Methodist start-up led by a Black female pastor in a mostly Black neighborhood. The church is committed to racial and gender equality. Its first principle is, “We show up.” That’s important to Dingle, now more than ever, because she’s not always able to sing praise songs attesting to God’s goodness.

“One thing we believe is that there are times when we need to lean on each other’s faith,” Dingle said. “I’m not going to pretend. There’s something wonderful about having others believe for me at moments.”

Her kids, three of whom are Black, feel more comfortable there, too.

Last week, the church held an outing at a local YMCA pool, a first for the family still functioning in lockdown mode since two of the youngest children are unvaccinated for COVID-19 and others are immunocompromised. Seeing the Dingle kids happily splash around in the pool felt redemptive, said the Rev. Lisa Yebuah, the church pastor.

“In the midst of all the things she has had to navigate, my hope for Shannon is that she will always be courageous enough to hold onto hope,” Yebuah said. “Not pie-in-the-sky hope. My hope is that she would see the trajectory of her life not only as pain but that there will be seasons that aren’t marked by tragedy. That’s my desire for her.”

The Dingle home, a brick ranch, houses seven humans, two dogs, and six cats. On a recent Friday morning, three housekeepers were sweeping the floors, wiping down surfaces, and returning objects to their place. Two of the younger kids were off at a summer school program; four others were busying themselves.

Dingle’s challenge looking after them as a single parent seems at times immense. She’s extremely grateful for a $339,000 GoFundMe campaign launched by friends after Lee’s death. That has allowed her to keep her family on health insurance and stay at home, which given her physical limitations — and especially during the pandemic — is all she could do.

Her daughter with cerebral palsy qualifies for a Medicaid waiver program that allows for a home health aide several hours a day. That helps, too. In addition, she said, she has allowed herself to accept help.

“There are a lot of people I text and they show up for things that I would never ask for before,” Dingle said.

On most days, that’s enough.

Recently, she had the house painted a royal blue. She had to think twice about whether to reattach a decorative metal house sign she and Lee had mounted that read, “This is our HAPPILY ever after.”

In the end, she hung it back up.