“Christian Nationalism doesn’t exist,” Franklin Graham declared to The New Yorker’s Eliza Griswold. “[It’s] just another name to throw at Christians.”

“Is this a term you fabricated? What does it mean and where have I indicated that I am a Christian Nationalist?” Doug Mastriano, the Pennsylvania state senator and GOP gubernatorial hopeful, also askedGriswold.

“Questions like ‘What does the governor believe about the Christian Nationalism movement that has been getting more attention since Jan. 6, 2021?’ — which are indistinguishable from ridiculous leftist political talking points — are indicative of the problem of overtly biased reporting that plagues the modern media,” a spokesperson for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis decried to Ana Ceballos of the Miami Herald.

Pleading ignorance about Christian Nationalism or dismissing the term as a partisan creation of progressives are frequent strategies of politicians accused of fitting the label. (The other response, occurring more frequently in recent months, is to redefine the concept and claim it as a badge of honor.)

The increasing usage (and contestation) of the term creates a risk. Those refusing to accept the reality of the term even as they advance Christian Nationalism do so because they fear the definitional power could threaten their ideological agendas. At the same time, some people frustrated by the power conservative Christians exert in U.S. politics add to the confusion by broadly applying the idea to any actions or language they find distasteful, acting as if any religious expression is somehow Christian Nationalism.

Precision matters here. Scholars and journalists who study Christian Nationalism offer insights into American public life, specifically into the evolving ways religion and politics intersect. Christian groups pushing back against the idea are making clear theological arguments about the essential character of Christian faith. Both of these conversations depend upon understanding what Christian Nationalism is and isn’t.

Perhaps the most common definition of Christian Nationalism is offered by sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry in their book Taking America Back for God. They “mean ‘Christian Nationalism’ to describe an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of American civic life with a particular type of Christian identity and culture.”

As Robert Jones, the founder of the Public Religion Research Institute, noted in his forward to the updated paperback edition of Whitehead and Perry’s book, “The central gift of this book, particularly for our politically polarized milieu, is its grounding of the term ‘Christian Nationalism’ — which has been bandied about, unproductively with competing anecdotal evidence — in empirical data.”

Whitehead and Perry achieved this by developing a Christian Nationalism scale based on survey data. Using common statistical techniques, they found that a stronger embrace of Christian Nationalism is associated with specific views about politics, race, gender, immigration, and religion. In other words, knowing how fervently someone adheres to Christian Nationalism allows you to predict their attitudes on a host of other issues. Thus, Christian Nationalism is an important concept that helps us understand how people view the world differently.

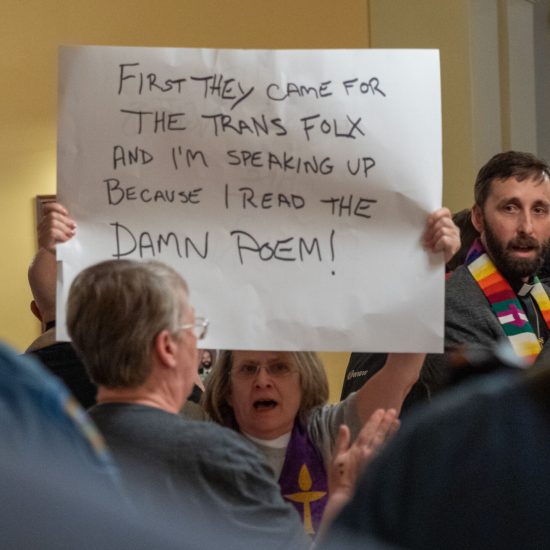

Controversy arises because Christian Nationalistic beliefs are connected to upholding what Samuel Perry, this time writing alongside Yale sociologist Philip Gorski in The Flag and the Cross, called an “ethno-traditionalism” where “Christian” is linked to retrograde understandings of gender, racial, and moral norms. Taken to the extreme, Christian Nationalist thinking threatens democracy by justifying the use of force and violence to realize this vision of the social order.

Given the growing public conversation about Christian Nationalism and divergent understandings of the meaning of the term, in this edition of A Public Witness we learn from scholars studying Christian Nationalism in order to consider what we actually know about this dangerous ideology. Then we hear the witness of committed followers of Jesus denouncing the “Christianity” that animates this belief system. Finally, we suggest practical ways of joining the growing pushback against the false prophets spreading this bad news.

NOTE: The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.