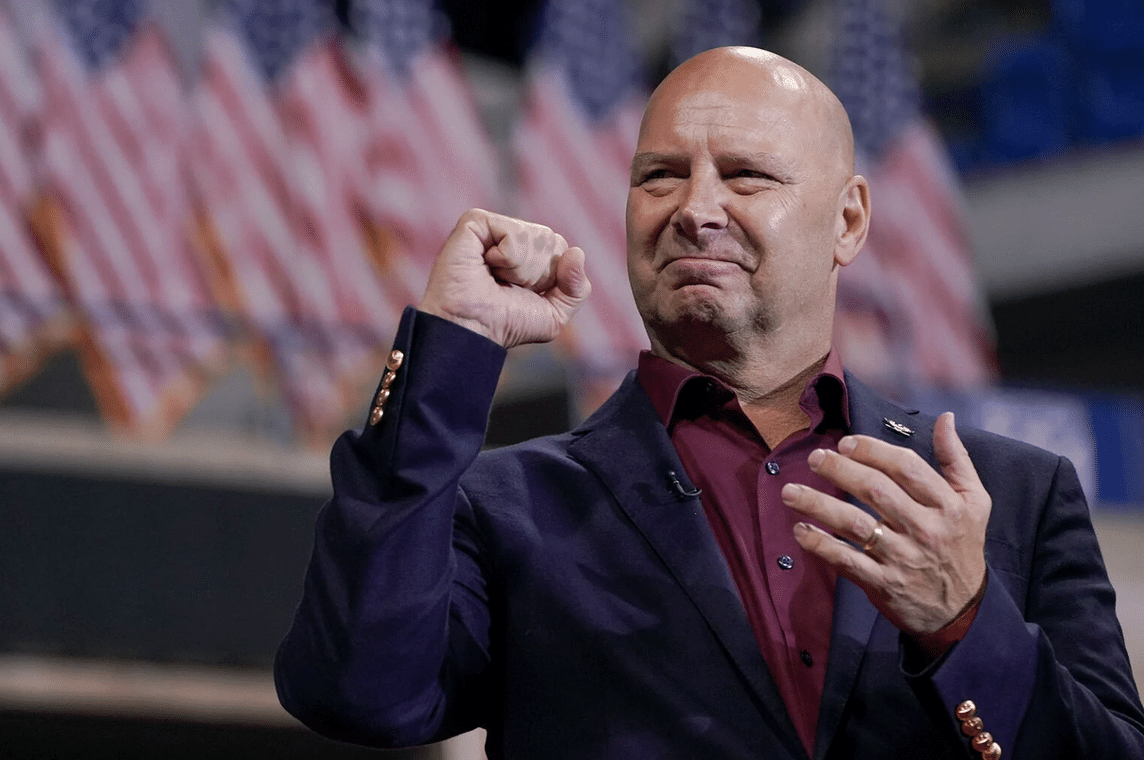

Pennsylvania Republican gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano speaks ahead of former President Donald Trump at a rally in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Sept. 3, 2022. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

GETTYSBURG, Pa. (RNS) — It’s well known that Doug Mastriano, the Pennsylvania state senator now running for governor on the Republican ticket, has a habit of energetically fusing religion and politics, giving voice to Christian nationalism and deriding the notion of separation of church and state as a liberal fabrication.

Among other things, the retired Army colonel has made headlines for appealing to the Almighty to overturn the 2020 election results and incorporating a reference to the Gospel of John (“Walk as free people”) into his campaign slogan.

But while some politicians have pivoted toward Christian nationalism this election season, Mastriano was not only leaning into the ideology years ago, but utilizing it as part of a larger pattern of distancing himself from criticism. Although he rejects the term Christian nationalist, Mastriano has invoked faith both as a fuel for his activism and a shield against detractors — including his fellow Christians, who remain concerned about his heavy-handed treatment of their beliefs.

In July 2020, more than a year before he declared his candidacy, Mastriano’s rhetoric sparked a theological battle with a group of prominent Lutheran clergy in his own state Senate district of Gettysburg, a rare example of the politician engaging directly with ideological foes. When the faith leaders invoked Christianity to criticize him, he responded by suggesting the Bible prohibits Christians from publicly criticizing elected officials, all while doling out his own condemnation of local religious leaders.

“He was telling us what to do in our churches,” the Rev. Maria Erling, a professor at the Gettysburg campus of United Lutheran Seminary who was among those who criticized Mastriano, told Religion News Service.

Mastriano has drawn fire for showcasing intolerance toward faiths not his own. A Rolling Stone report turned up a 2019 radio interview in which he said Islam is “not compatible” with the “Christian-Judeo ideas” of the U.S. Constitution, and “not all religions are created equal.” Jewish groups have decried his association with Andrew Torba, head of the social media site Gab, where antisemitic messages and memes are often shared. (Mastriano later deleted his Gab account and condemned antisemitism, although he did not condemn Torba.)

But Mastriano’s dispute with his Lutheran constituents shows he’s equally willing to reject the voices of other Christians, particularly views often expressed by moderate and liberal Lutherans, Presbyterians, Methodists and others known collectively as “mainline” denominations (named, some scholars argue, for the affluent suburban Philadelphia Main Line communities, where these congregations flourished). Although not as dominant as they once were, white mainline Protestants nonetheless represent 18% of Pennsylvanians — equal to the number of white evangelicals in the state, according to the Public Religion Research Institute.

Mastriano, for his part, has been linked to Pond Bank Community Church, a conservative Mennonite congregation. Church officials did not respond to requests to confirm that Mastriano is a member, nor did Mastriano respond to multiple interview requests.

Mastriano’s debate with the Lutherans dates back to a since-deleted interview with a couple, Allen and Francine Fosdick, self-described Christian prophets with an online ministry called People of Prophetic Power Ministries.

“‘Separation of church and state’ — anyone who says that, show me in the Constitution where it says it,” Mastriano told the Fosdicks while sitting at his desk in the Pennsylvania state Capitol. “It’s not in there. It’s never been in there.” In a formulation that has become popular among conservatives, Mastriano added, “We have freedom of religion, not freedom from religion.”

Mastriano, who was gaining popularity in conservative circles at the time for strident opposition to COVID-19 restrictions, referred to a “fake COVID crisis” and chided his fellow lawmakers who had imposed limitations on large gatherings in Pennsylvania. He insisted Christians should show more “courage” in resisting lockdown measures and offered as a model Martin Luther, the 16th-century founder of Lutheranism and leader of the Protestant Reformation.

“Pastors, it’s time for you to lead,” Mastriano said in the video, which later disappeared when the Fosdicks’ YouTube account was revoked for violating the company’s guidelines. (A mirror of the video remains accessible on an archival website.) “If that pastor — and others — doesn’t want to open up, then congregation, maybe it’s time to find another church where they have a little more courage.”

As he put it in another part of the interview: “I’d like to see the churches stand up — we have strong religious freedoms in Pennsylvania.”

Local churches did, in fact, stand up, albeit perhaps not the way Mastriano intended. Forty-six local Lutheran leaders — including vicars, former seminary presidents and the pastor at St. James Lutheran Church, a few doors down from Mastriano’s local office — published a full-page ad in the Gettysburg Times supporting many COVID-19 restrictions and rejecting Mastriano’s interpretation of their denomination’s namesake. The ad cited the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s position, which quoted Luther to argue that Christian decisions should “always be made in the best interests of the neighbor.”

“The senator’s interpretations of scripture and Luther’s actions in the Protestant Reformation are taken out of context to serve his political agenda,” the ad read.

Their voices carried weight in the town, where the oldest continuously operating Lutheran seminary in the country occupies a prominent part of the local landscape — and U.S. history. Founded in 1826, the school’s red brick buildings sit atop a hill known as Seminary Ridge, a strip of land that traded hands between the Army of the Potomac and the Confederacy in 1863 in the Civil War battle that made the town famous.

The seminary is known today as the Gettysburg campus of United Lutheran Seminary, which also has a campus in Philadelphia. Sitting in the seminary’s library and leaning over an archival text, Erling, a professor of modern church history and global mission, recalled the debate with Mastriano with barely disguised frustration. She doesn’t impugn his personal faith, she said, but has little regard for his public theology.

“I don’t take him seriously as a religious voice at all. I absolutely do not,” said Erling.

Publicly criticizing Mastriano’s faith musings wasn’t something the group did lightly, she said — among other things, she and her fellow clergy had to pay for the ad themselves. But Erling argued the state senator left them no choice.

“He was saying that people should not go to the churches unless they’re complying with his ‘walk as free people,’ and that any restrictions are not of Christ,” she said. “He hit a ball into our court.”

According to a Pew Research survey from the time, only 6% of churches or houses of worship were conducting worship services as they had before COVID-19 struck. Some 31% were not open for in-person services at all. A separate University of Chicago Divinity School/AP-NORC poll conducted in May 2020 found that more than half (52%) of white mainline Protestants said in-person services should not be allowed.

Mastriano fired back at the Lutherans in a Facebook Live video, calling their message “hateful” and describing them as “modern Pharisees” that include people with a “hostility toward Jesus Christ.” He railed against the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s more liberal position on abortion rights.

“They wear the name of Christ, but they don’t act as Christians,” Mastriano said of the clergy.

Mastriano also argued that he could dismiss the pastors’ allegations, citing the Gospel of Matthew, saying they were bound to approach him as Christians before publishing their remarks. “We can completely discount their allegations, because they have a form of godliness, but deny the power thereof,” he said.

The video soon vanished from Mastriano’s Facebook page without explanation, but later that week he was asked about the ad on a local radio program. He insisted he was “not at war with any denomination” but accused the clergy of favoring his Democratic (and Lutheran) opponent, Richard Sterner.

Mastriano went on to cite the 13th chapter of the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans, a New Testament passage sometimes interpreted to mean Christians should respect the power of governing authorities. “They’re actually supposed to pray for me and support me as their government leader,” he said, referring to the Lutheran pastors. “I’m over them politically. I’m their senator. I represent them. And instead of engaging me with civility, they have a political hack job.”

The episode sheds light on just how Mastriano mixes faith and government by quashing dissent, even dissent coming from Christians, on religious grounds.

That approach still troubles the Rev. Timothy Seitz-Brown, a Lutheran pastor in Pennsylvania’s Lower Susquehanna Synod who regularly participates in activism at the state Capitol.

“I’m concerned, if he gets elected, what I’m going to be risking” by continuing with activism, Seitz-Brown said. “Is (Mastriano) going to treat clergy like me, that he disagrees with, with a hard heart and soft feet, or is he going to have a soft heart and at least listen a little bit?”

Critics have also pointed out that Mastriano, who was in the crowd outside the U.S. Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection and spoke at “Jericho Marches” that denied the results of the 2020 election in the days before the attack, has not shown the deference to authority he insists Paul demanded. (Mastriano has insisted he left the Capitol grounds when things turned violent, although his exact account of the day has been disputed.)

The Rev. Taylor Berdahl, who signed the open letter and now serves as pastor of St. Matthew Lutheran Church in nearby Hanover, said the ad was meant to be a defense of faith, not an attack on Mastriano. The letter, she said, was “far more about ideas and faithfulness to the theological witness of what we have some responsibility to maintain and teach than about the person of Mastriano.”

But she took issue with the candidate’s interpretation of Romans 13. Reading it through Luther’s views, Berdahl argued that while Christians should have “a respect for those who have government authority,” Jesus Christ models the need to voice faithful dissent when necessary.

“In the way that Jesus did in his lifetime, when there is overreach of government, when there is oppression enacted by governments, our faith also moves us to speak out against those things that are harming the people that we are called to love and serve on behalf of Jesus Christ,” she said.

She added: “We worship God. We do not worship our elected officials.”

This story was produced under a grant from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation and presented as part of the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort to shine a light on the threats and opportunities facing American democracy. Read more at usdemocracyday.org.