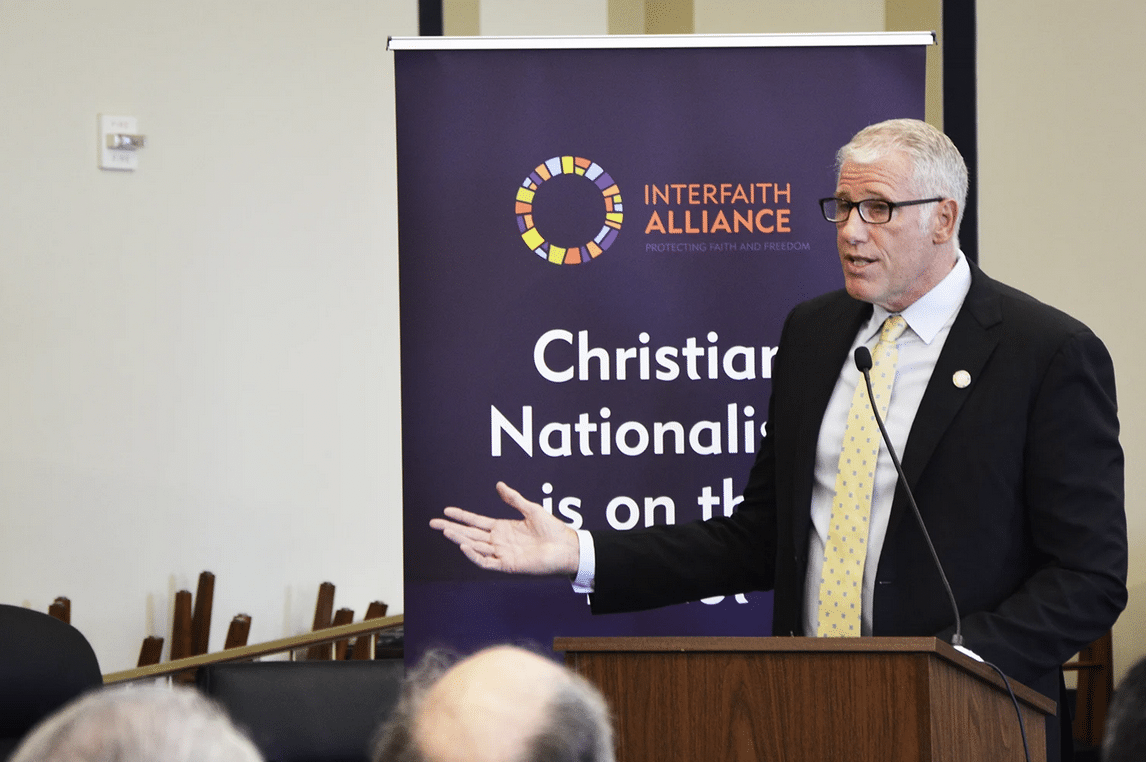

Rev. Paul Raushenbush, President and CEO of the Interfaith Alliance, speaks during a panel hosted by the organization on Christian nationalism. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

WASHINGTON (RNS) — An interfaith group of activists and religious advocates voiced concerns about the rise of Christian nationalism on Wednesday (Sept. 28), arguing the ideology is a threat to democracy during a briefing on Capitol Hill.

“We are convening this Christian nationalism briefing because we feel it represents a clear and present danger to our democracy and to an inclusive vision of religious freedom,” said the Rev. Paul Raushenbush, head of the group Interfaith Alliance, which organized the event.

Speakers at the hourlong briefing outlined what they said were specific threats posed by Christian nationalism, a fusion of faith and national identity that swelled during the tenure of former President Donald Trump and has continued to gain steam ever since.

Author and lawyer Wajahat Ali noted the visibility of Christian nationalism during the attack on the U.S. Capitol that took place on Jan. 6, 2021. He said it has become common to hear versions of the ideology articulated by Republicans ahead of this year’s midterm elections.

“Christian nationalism was a major motivator for the violent coup that sought to overturn the free and fair election by any violent means necessary,” Ali said, referring to Jan. 6. “Fast-forward to today, and we have GOP Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene openly embracing Christian nationalism and palling around with antisemitic white nationalist Nick Fuentes.”

Fuentes, a right-wing extremist who heads the group America First, has begun openly identifying as Christian nationalist, as has Greene. Meanwhile, Republican candidates such as Pennsylvania’s Doug Mastriano have given voice to versions of the ideology on the campaign trail.

Ali, who is Muslim, noted members of his faith have long been targeted by Christian nationalists, and he referred to the ideology as the “greatest threat to our national security today.”

“Another word for this growing Christian nationalism movement is fascism,” he said. “Another word is national security threat. Another word, in specific contexts, is terrorism.”

Connie Ryan, who serves as executive director of Interfaith Alliance of Iowa, specified more local concerns. Ryan argued Christian nationalism has driven efforts in her state to allow for Bible classes in public schools, as well as what she described as an overall “demonization” of public schools and the teachers who work there.

“We have legislators who would have been moderate five, six, seven years ago, and they are moving and shifting toward Christian nationalism,” she said.

Tayhlor Coleman, a voting rights advocate who has been touring Texas in a van converted into a “voter registration mobile,” said the rise of Christian nationalism and its impact on the Capitol insurrection reminded her of America’s racist past. She recounted when white racists stormed majority-Black voting precincts in Texas during Reconstruction, sparking violence that resulted in lynchings.

“When I look at the folks who are leading this (Christian nationalist) movement, I don’t see any Christianity,” Coleman said, adding that she was raised Southern Baptist. “What I do see is the very same racism we always have.”

Multiple speakers noted the influence of Christian nationalism among white evangelicals in particular, citing a recent poll that revealed three-quarters of Republican evangelicals support the federal government declaring the country to be a Christian nation.

However, the Rev. Richard Cizik, executive director of Evangelicals for Democracy and onetime staffer at the National Association of Evangelicals, suggested some in his tradition may be moving away from Christian nationalism — particularly younger churchgoers. His organization, he said, is hoping to reach persuadable evangelicals ahead of the midterms with targeted advertisements that focus on biblical concepts of love. Challenging Christian nationalist ideology, he said, could spur his fellow faithful to rethink their approach to politics.

“Christian nationalism often influences behavior in the opposite direction — other than traditional religious commitments,” he said. “Therefore, being an evangelical doesn’t sour one to gun control, but Christian nationalism does. Same thing with border walls with Mexico.”

Rep. Jamie Raskin, Democratic congressman from Maryland who serves on the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection, was also slated to speak, but instead ended up on the House floor during the event. Even so, Raushenbush told Religion News Service Raskin and his staff made the briefing “possible,” and celebrated the willingness of some lawmakers to speak out against Christian nationalism.

“This is not about anti-Christianity, and it is not about anti-patriotism,” said Raushenbush, a Baptist minister. “It is about recognizing this particular manifestation.”

Raskin has publicly acknowledged the role Christian nationalism played in fueling the insurrection, as has fellow Jan. 6 committee member Rep. Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, himself an evangelical Christian who has condemned the ideology by name. Raskin, who told RNS in May of last year that he read the book “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation” to better understand evangelical support for Trump, was also among a group of lawmakers who attended a virtual briefing in March led by activists and scholars on a report detailing Christian nationalism’s outsized influence on Jan. 6.

However, Christian nationalism has not been directly mentioned during the Jan. 6 hearings themselves, with lawmakers instead often highlighting the faith of those negatively impacted by the Capitol attack. Meanwhile, few Republican lawmakers — aside from Kinzinger — have condemned or distanced themselves from fusions of God and country amid calls from Greene for the GOP to become the “party of Christian nationalism.”

Even so, Ali said Raskin’s affiliation with the event is important, given the congressman’s role as “one of the folks who has been sounding the alarm about our national security threats.” More attention should be paid to Christian nationalism because, Ali argued, it will likely outlive Trump’s time on the national stage — especially as governors such as Gregg Abbott of Texas and Ron DeSantis of Florida embrace the ideology alongside others popularized by Trump.

“People say when Trump is gone, the spread is gone. Nope — Trumpism is here to stay,” Ali said. “It will just create a new avatar. That avatar right now is DeSantis, Abbott and Marjorie Taylor Greene.”