ATLANTA (AP) — One candidate in Georgia’s Senate contest warns that “spiritual warfare” has entangled America and offers himself to voters as a “warrior for God.” But it isn’t the ordained Baptist minister who leads the church where Martin Luther King Jr. once preached.

It’s Republican Herschel Walker, the sports icon who openly questions the religious practices of Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock, who calls himself “a pastor in the Senate” and declares voting the civil equivalent of prayer.

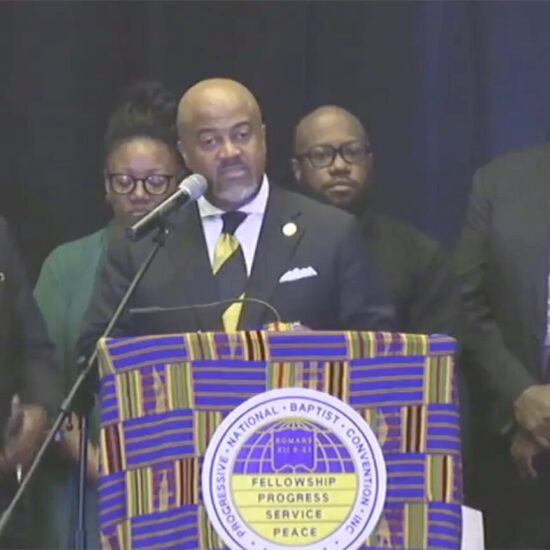

Rev. Raphael Warnock speaks at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, on Jan. 12, 2018. (David Goldman/Associated Press)

Both men feature faith as part of their public identities in a state where religion has always been a dominant cultural influence. But they do it in distinct ways, jousting in moral terms on matters from abortion, race, and criminal justice to each other’s personal lives and behavior. Their approaches offer a striking contrast between political opponents who were raised in the Black church in the Deep South in the wake of the civil rights movement.

“It’s two completely different visions of the world and what our biggest problems actually are,” said Rev. Ray Waters, a White evangelical pastor in metro Atlanta who backs Warnock in Tuesday’s election.

How religious voters align could help decide what polls suggest is a narrow race that will help settle which party controls the Senate the next two years. According to Pew Research, about 2 out of 3 adults in Georgia consider themselves “highly religious.”

Warnock, 53, preaches a kind of social justice Christianity that echoes King, the slain civil rights leader who also led Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. The senator embraces the Black church’s roots in chattel slavery and Jim Crow segregation. From the pulpit, he acknowledges institutional racism and calls for collective government action that addresses inequities and other social ills. He often notes his arrests as a citizen protester advocating for health insurance expansion in the same Capitol where he now works as a senator.

“I stand up for health care because it’s a human right,” Warnock said. “Dr. King said that of all the injustices, health care inequality is the most shocking and the most inhumane.”

Walker talks, too, of society’s shortcomings, but the 60-year-old points to the expansion of LGBTQ rights, renewed focus on racism and “weak” politicians, who, he says, “don’t love this country.” He has called for a national ban on abortions but has faced accusations from two former girlfriends who said he pressured them into terminating pregnancies and paid for their procedures. He has said the claims are lies.

It’s a culturally conservative pitch tied to individual morals rather than collective responsibility and effectively holds that the United States is a Christian country. That aligns Walker with the mostly White evangelical movement that has shaped the modern Republican Party.

Those approaches, varied in substance and style, are traced through the two rivals’ biographies.

Warnock, the son of Pentecostal ministers, pursued a similar educational path as King. Both attended Morehouse College, a historically Black campus in Atlanta. Warnock followed that with Union Theological Seminary in New York, a center of progressive Christian theology. Now with more than a decade in one of the nation’s most famous pulpits, he sometimes quotes Scripture at length and peppers his arguments with Latin references.

“I believe a vote is a kind of prayer for the world we desire … and that democracy is the political enactment of the spiritual idea that each of us was created, as the scriptures tell us, in the ‘Imago Dei’ — the image of God,” Warnock told a group of Jewish supporters last month.

At the same event, during observances of the Jewish New Year, Warnock noted a passage often used as part of Rosh Hashanah fasting. “Is this the fast that the Lord is looking for,” he said, “that you would loose the chains of injustice and you would set the oppressed free, that you would feed the hungry, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger.” Offering the citation — Isaiah 58:6 — he called it “a favorite of mine.”

Walker also is a Pentecostal pastor’s son and now attends nondenominational Bible churches. A star high school athlete in rural Georgia, his football prowess took him in 1980 to the University of Georgia, a secular public campus that was then overwhelmingly white. Walker never graduated, though he claims otherwise. He talks often of Jesus, typically as a figure of “redemption” rather than a guide for public policy.

“Let me acknowledge my Lord and savior Jesus Christ, because it’s said if you don’t acknowledge him, he won’t acknowledge you,” Walker said at his lone debate with Warnock. “When I come knocking, I want him to let me in.”

Many Walker events open with prayers, some led by other Black conservative evangelicals. Yet Walker’s scriptural and theological references are scattershot, usually nonspecific allusions as part of broadsides against Warnock and “wokeness.” On transgender rights, Walker has said: “I can’t believe we’re discussing what is a woman. That’s written in the Bible. … We got to not let them fool us with all those lies.”

At a “Women for Herschel” event in August, Walker suggested Warnock is anti-American, and he alluded to the biblical story of the Hebrew God expelling dissident angels from heaven. “It’s time for us to kick those people who don’t like America, kick ‘em out of office,” he said, concluding to his largely white audience: “Don’t let anyone tell you you’re racist.”

On abortion, he said directly to Warnock on the debate stage: “Instead of aborting those babies, why are you not baptizing those babies?” It’s a compelling argument for voters such as Wylene Hayes, a 76-year-old retired schoolteacher in Cumming.

“You can just tell Herschel is a man of strong faith, and just humble,” she said. “I don’t have anything against Sen. Warnock, but I do question how he can be a pastor and support abortion.”

Warnock counters that he supports abortion access because “even God gives us a choice,” while Walker’s position would grant “to politicians more power than God has.”

Waters said Walker’s collective argument is targeted squarely at white suburban Christians like those he led for decades before moving closer to the Atlanta city center, where he saw more problems to fix and people to help. “It seems to me the central issues in wokeness are … compassionate habits that are a lot of what Jesus said to do,” Waters said.

Warnock largely sidesteps Walker’s attacks. He has recently begun framing Walker as “not fit” for the Senate because of Walker’s “lies” about his business record and allegations of violence against his ex-wife. The closest Warnock comes to questioning Walker’s faith is to say redemption requires that a person “confess … and be honest about the problem.”

“I will let him speak for himself,” Warnock said. “I am engaged in the work I’ve been doing my whole life.”

Rev. Charles Goodman, an Augusta pastor and friend of Warnock, said it’s not new for outspoken Black pastors, especially those with a more liberal theology, to be tarred as dangerous and anti-American.

“They called Dr. King a ‘communist,’ and now it’s ‘radical’ and ‘socialist,’” Goodman said. “Dr. Warnock loves this country. There will always be tensions between our aspirational views of the country versus our struggle trying to get to that place. He’s a very hopeful minister, and he’s always going to speak truth to power and live in that tension.”