For the Fourth of July last year, Republican U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri wanted to push his version of Christian Nationalism, so he tweeted a quote from Patrick Henry — the U.S. founder famous for declaring, “Give me liberty or give me death.”

“It cannot be emphasized too strongly or too often that this great nation was founded, not by religionists, but by Christians; not on religions, but on the gospel of Jesus Christ,” Hawley shared with his 1.4 million followers as Henry’s words.

Only problem is Henry never said that.

The quote actually comes from a 1956 article by someone else (since Henry had been dead for over 150 years by that point). In a 1989 book attacking the constitutional idea of church-state separation, evangelical pseudo-historian David Barton, a mentor of Speaker Mike Johnson, apparently read the piece incorrectly and attributed the words to Henry. After numerous scholars pointed out its real origin, Barton retracted that and other false quotes he used to claim U.S. founders wanted a “Christian” nation.

But the zombie quote lives on, frequently used by those pushing Christian Nationalism to justify their ideology and policies. After Hawley tweeted it out, numerous scholars and journalists quickly noted the quote was fake. Unrepentant, Hawley left the fake quote up, refused to apologize or even admit the deception, and instead claimed people were attacking him for pointing out history. He tweeted the next day, “I’m told the libs are major triggered by the connection between the Bible and the American Founding.”

After fist-pumping for Christian Nationalism and running away from the truth, Hawley doubled down on his effort to undo our constitutional system.

Since then he has continued his quest to rewrite history with misleading claims. In October, he penned a piece for Compact magazine arguing conservatives should fight to create a “Christian democracy for America.” Now, he’s gone even further in a nearly 4,400-word essay for First Things, a conservative Christian magazine whose editor in 2016 quickly shifted from “Never Trump” to endorsing Trump and transforming the publication in that direction. Founded by the late Catholic priest Richard John Neuhaus, it has become a leading Christian platform for pushing nationalism.

Hawley’s piece, the main article in the February issue (and already published online), notes his vision from the start with its title: “Our Christian Nation.” And while he doesn’t attempt to quote Patrick Henry in the piece, the essay suffers from the same misunderstanding of U.S. history along with misrepresentations of Christianity. It also advances the cause of Christian Nationalism with odd arguments and non sequiturs.

But it’s not merely an intellectual exercise. The bad history and theology are necessary to justify dangerous public policies. The senator who became the congressional face — and fist — of the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection wants to get his hands on much more than just our elections.

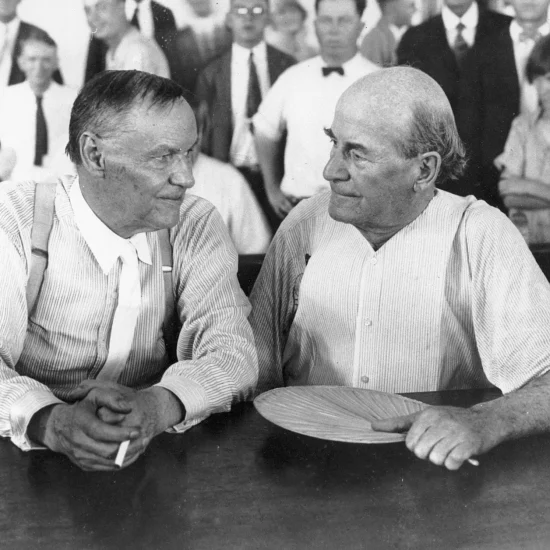

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) gestures toward a crowd of Donald Trump supporters gathered outside the U.S. Capitol to protest the certification of Joe Biden’s electoral college victory on Jan. 6, 2021. (Francis Chung/E&E News and Politico via AP)

Given his prominence as a U.S. senator generally expected to mount a presidential campaign in a future cycle, his essay offers an important — and alarming — look at a vision to remake America into a place that privileges a narrow slice of conservative Christianity. So this issue of A Public Witness considers Hawley’s argument for “our Christian nation” to unpack where he’s wrong and why it matters.

Dissenting Voices

As his essay’s title notes, Hawley argues in the piece that “America has been a Christian nation.” He insists the founders intended that, even though they didn’t mention it in their writings or in the Constitution (where they instead prohibited religious tests for office).

Given the lack of evidence about a desire for a “Christian nation” from important figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Hawley instead looks elsewhere to back his claim. So he repeatedly invokes the Puritans, including John Winthrop, a British colonist from before the founding era. Hawley cites Winthrop’s idea of the new land as a “city upon a hill” (from a speech in which Winthrop also offered a theological foundation for the genocide of Native Americans). But Hawley leaves out the other side of the debate in Winthrop’s colony about the role of religion in government.

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.