THE EXVANGELICALS: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church. By Sarah McCammon. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2024. 310 pages.

Much has been made in recent years about the decline in membership in the so-called Protestant Mainline. The decline has been steep. On the other hand, we’ve been told that conservative evangelical churches are growing. It’s true that huge megachurches have popped up all across the country, and that many of them are filled with young adults and their children. However, there is another trend underway. That trend involves scores of people, of all ages, but especially younger adults, leaving, even fleeing evangelical churches. The reasons are various but often have to do with matters of sexuality, politics, racism, science, and scandal. While some retain aspects of their faith others have completely walked away. So we’re beginning to see and hear the stories of these refugees from evangelicalism.

Robert D. Cornwall

Among those who have been telling these stories is Sarah McCammon, who is a National Political Correspondent for NPR and cohost of the NPR Politics Podcast. In other words, she’s a journalist who knows how to tell stories that connect with readers. She tells her own story and that of others, who like her, left behind their evangelical roots. She does so in the book titled The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church.

The term Exvangelical is one of several that have been used to describe what is happening, especially among white evangelicals. She chose a term that is broader than another term that has become prominent, that is post-evangelical. The term post-evangelical tends to cover people who left evangelicalism but seek to find ways of reconnecting with the Christian community. Some join mainline churches, but others are seeking other forms of community. Exvangelicals include post-evangelicals, at least as I understand the terms, but also it includes people who are still searching or have completely left behind their Christian faith. They may be atheists, but not necessarily.

I am grateful to McCammon for telling her story, and that of others, because it gives insight into the struggles that so many are having with evangelicalism, especially in the age of Trump. Although we need to acknowledge that Trump largely took over a “movement” that was already forming but simply needed a figurehead. Before I get into the book itself, I want to place myself in the larger story, because I believe McCammon has helped me distinguish my experience as someone who left evangelicalism decades earlier, but whose departure was more an evolution than a flight from evangelicalism. Perhaps one of the reasons for the differences, besides the generational one (I grew up in the 60s and 70s, while she grew up in the 80s and 90s), is that unlike McCammon and many of the people whose stories she shares, I was not raised in evangelicalism. I was born into an Episcopalian family. Then in high school, I “converted” to a form of Pentecostalism. I dove deep into the waters, but it appears that my roots weren’t as deeply planted. Thus, my “deconstruction” if you want to call it was not nearly as traumatic as what McCammon experienced as one born into a deeply evangelical/Pentecostal family. Unlike me, she was raised on the teachings of James Dobson and others like him. That makes a difference.

What we have in this book is the story of the Exvangelicals, people who have been deconstructing from what had been their deeply held evangelical beliefs and practices. Many who make up this movement are LGBTQ+, non-white, female, or members of other marginalized identities.” They may be part of what she describes as a “loosely organized, largely online movement of people who are trying to make sense of the world as it is, and who they are in it” (p. 4). She traces the term to sometime around 2016 and is credited to Blake Chastain, who started a podcast with that title at that time. A movement emerged as former evangelicals seek to rethink their view of the world and themselves. She points out that those who form this loosely defined movement have pursued different pathways from working to reform evangelicalism to walking completely away from their faith. There may be a sense of relief at the freedom this brings, but also sadness, especially at the loss of former relationships, which can, as we see in the book, include broken family relationships.

Much of the book is rooted in McCammon’s own story, but it’s not just her story. We start, however, in chapter 1, titled “People Need the Lord,” with the beginnings of her childhood story, and the prayers she offered for her paternal grandfather, who was an atheist. She worried about him because she feared, as she had been taught, that unless he said yes to Jesus, he would be condemned to hell. We learn about her family and its deep commitment to their evangelical (Pentecostal) faith. For the most part, she lived a rather isolated and sheltered life, rooted in the church, family, and Christian schools. Leaving evangelicalism has helped break through that isolation, and what she experienced is common to many others.

With that introduction to her evangelical origins, we move into Chapter 2, a chapter titled “A ‘Parallel Universe,’” to a deeper discussion of the evangelical movement into which she was born in 1981. She writes that the belief system she was raised in “took the fundamentalism of an earlier era, with its traditional gender roles and literalistic interpretation of the Bible, and repackaged it with a more accessible, modern gloss. This was more than merely a religion, or even a path to eternal salvation; the evangelicalism of my childhood offered a relationship with God and with a young, energetic community, led by confident, telegenic preachers who promised guidance and offered a vision for both families and a nation dedicated to carrying out what they saw as the will of God” p. 32). I was there during the early stages of this movement but didn’t stay long enough to be fully baptized into it. What she describes here is the alternative universe that included Christian schools that taught Young Earth Creationism and alternate views of history (A David Barton view). Interestingly, she reports that some who have left the movement itself have actually moved further to the right politically, but the seed was already planted.

The first two chapters provide the foundation for what is to come. It helps us understand the lay of the land. Then in Chapter 3, titled “An Exodus,” McCammon begins to share how and why those deeply rooted in evangelicalism began to leave, especially in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election in 2016 and subsequent alignment with conservative evangelicalism. McCammon, who had already left her evangelical roots by then, was assigned by NPR to cover Trump’s campaign. Thus, she brought a distinctive view to the emergence of the Trump-Evangelical alliance.

Her “Unraveling” (Chapter 4) came long before the rise of Donald Trump. In this chapter, we learn more about her experiences as a Senate page. Some of what she shares is rather disturbing. It is in this chapter that shares the beginnings of the unraveling of her faith, including her own sexual awakening and struggles to make sense of what she was feeling and what she had been taught. But we also learn about her exposure at college to life outside evangelicalism, including connecting with Muslims and Jews.

McCammon titles Chapter 5 “Were You There?” Here we return to the form of conservative evangelicalism to which she was exposed, one that embraced such things as Young Earth Creationism, as expressed through Ken Ham and Answers in Genesis. In this chapter, she shares how she and others found what they were taught at church incongruous with what scientists shared. That leads to the “Alternative Facts” of Chapter 6. This chapter explores the alternative Christian Worldview, that offered a different set of “facts,” a concept that the Trump campaign and White House embraced, but which conservative evangelicals were set up to embrace. This is rooted in a form of anti-intellectualism that pervaded the movement and has made the movement susceptible to conspiracy theories and anti-science views (see the resistance to COVID-19 vaccines and guidelines).

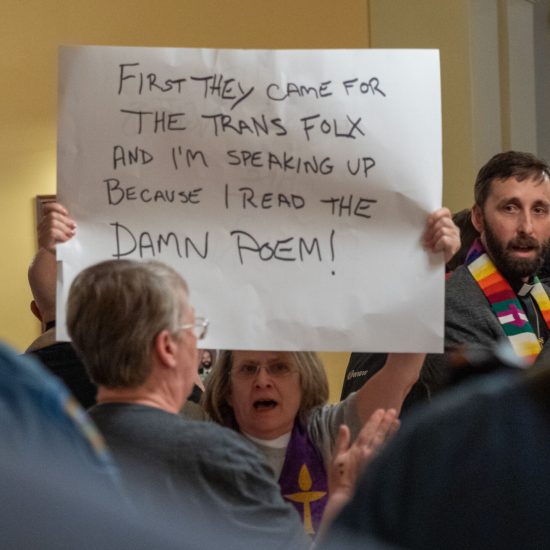

One of the baffling elements of the evangelical embrace of Donald Trump has been the abandonment of the belief that character matters, something explored in Chapter 7 — “Whose ‘Character” Matters?” The same movement that rejected Bill Clinton because of his lack of moral character decided that character didn’t matter when it came to Donald Trump. Thus, James Dobson who emphasized the need for character decided that it no longer mattered, at least if they had a champion for their agenda, something Trump was willing to offer. This led to more exits from evangelicalism, as important figures in the movement such as Beth Moore broke with their denominations over the embrace of Trump. For some who exited evangelicalism, there was a determination to “Leave Loud” (Chapter 8). That is, some former evangelicals decided to make a loud declaration of their disgust at what was happening.

In this chapter, McCammon shares the stories relating to race and racism as well as civil rights. If Chapter 7 explored the question of character, and Chapter 8 explored the question of race and evangelicalism, Chapter 9 — Whom Does Jesus Love? — examines the question of sexual identity and orientation. Here again, is a leading cause of departure from evangelicalism, which remains largely anti-LGBTQ, such that those who either identify as LGBTQ or support them no longer feel able to stay within a movement that is a threat to their mental and physical health. Here, McCammon shares the story of that Grandfather who didn’t believe, but who also later in life came out as gay. This relationship allows her to tell the story of her own family and that of others.

A number of books have appeared lately that describe the “Purity” movement in evangelicalism. McCammon was introduced to it herself, so she has her own story as well the stories of others about the nature of this movement and the damage that it has done. These stories appear in Chapter 10: “A Virtuous Woman.” She discusses the question of sexuality further in Chapter 11: “Naked and Ashamed.” In this chapter, she talks about the questions of sexual anxiety and marriage. Chapter 12 takes the conversation another step, to the question of the role of children. That is, the call to “Be Fruitful and Multiply” and the evangelical embrace of the anti-abortion movement. At a young age, McCammon was introduced to this movement, even spending time as a teen volunteering at a “Crisis Pregnancy Center,” with the responsibility of talking women out of getting an abortion. If Chapter 12 focuses on the anti-abortion movement, Chapter 13 — “Suffer the Little Children” — focuses on childraising, especially as taught to evangelicals by James Dobson through such books as Dare to Discipline. Here we learn about some of the perhaps unintended consequences, such as child abuse.

The reasons for departing evangelicalism are many, as we’ve already seen. However, there is more to come. Thus, in Chapter 14, titled “Broken for You,” McCammon talks about the role teachings on the second coming and the rapture have played in the lives of evangelicals. She shares how these teachings were expressed and their impact on people. For her, and many, this was traumatic and one of the causes, though not the only cause, of religious trauma.

As we near the end of the book, McCammon turns to the aftermath of departures. She titles Chapter 15 “Into the Wilderness.” This is a chapter on the freedom experienced by many who leave evangelicalism and the question that emerges as to where one goes from there. She writes that she asks herself this question almost every day: “Once you’ve discovered that the world you called home is no longer a place you can comfortably reside in, where do you go? What will you find along the way? And who might you become? For those of us wandering out of evangelicalism, we can find ourselves in a foreign — and often frightening — spiritual and emotional wilderness” (p. 217). This is, I believe, a very important chapter because it’s one thing to leave something that has been formative of one’s view of the world, so leaving that behind can be traumatic in itself. So, she explores some of the pathways people take.

One thing that those on the pathway are discovering, is that they’re not alone. One of the challenges faced by those who go into the wilderness is the accusation by those left behind of apostasy, something McCammon has been accused of by a member of her own family. So, she addresses these challenges in “Wrestling Against Flesh and Blood” (Chapter 16). The challenge for those who leave, especially those who have been ostracized, is avoiding a different kind of fundamentalism. She notes that “wounded people have a natural instinct to push back, to protect themselves. And for those who grew up in the culture wars—who’ve been trained to fight, and to fight hard—laying down the sword, taking off the armor, and tending those wounds is one of the biggest battles of all” (p. 247). I’ve seen examples of this, so it is a very real area of concern.

The final chapter is titled “Into All the World,” which is a very biblical expression (Chapter 17). Here McCammon brings the story to a close, sharing something of her own sense of place at this moment. You can tell that she is at peace, but it was a struggle to get there. But for many the trauma continues to impact their lives. One thing she has discovered is that for her, she’s still attached to Jesus and his story. She may not believe that people need the Lord to thrive, but she finds in Jesus a calling, something she learned from her grandfather, and that is, to help others. That is what this book is about.

My journey with and out of evangelicalism, as I knew it, was different from what Sarah McCammon has experienced. Like many of earlier generations, I found a home in Mainline Protestantism (I’m a Disciples of Christ minister and theologian), but that doesn’t seem to be as common a destination today. I wish it were for the sake of our churches, but perhaps our realities do not provide the kind of home many need. That being said, reading McCammon’s book, along with others like it, has helped me better understand the traumas and challenges faced over the years by people raised in evangelicalism.

Finding a sense of wholeness and healing is important. To get there it is helpful to know that you’re not alone. What McCammon does so well in telling her story and those of others is to let people know they’re not alone. That’s a good starting point for finding healing. What I’ve tried to do here is give a sense of what can be found in this very important book on The Exvangelicals, so that others whether evangelical, exvangelical, post-evangelical, or simply people of faith or no faith who seek to understand the realities faced by many who find themselves in the wilderness after leaving a world, White Evangelicalism, that had formed them and at times wounded them.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.