“Every teacher, every classroom in the state will have a Bible in the classroom and will be teaching from the Bible in the classroom.”

Oklahoma State Superintendent of Public Schools Ryan Walters made that announcement recently as he issued a memorandum to require the teaching of the Bible in public schools. He insisted “adherence to this mandate is compulsory” for all districts and teachers. Walters made the move two days after the state’s Supreme Court ruled against the creation of the first publicly-funded religious charter school — a sectarian effort backed by Walters. He’s also pushed other efforts to bring Christianity into the state public school system he oversees.

The move by Walters quickly sparked criticism and threats of litigation. Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State (where I serve as a board member), blasted Walters’s Bible directive as “a transparent, unconstitutional effort to indoctrinate and religiously coerce public school students.”

“Public schools are not Sunday schools,” she added. “This is textbook Christian Nationalism. Walters is abusing the power of his public office to impose his religious beliefs on everyone else’s children.”

With the new school year starting in just a few weeks, eight large school districts in the state have already announced their teachers don’t need to add a Bible to the school shopping list.

“I’m just going to cut to the chase on that. Norman Public Schools is not going to have Bibles in our classrooms, and we are not going to require our teachers to teach from the Bible,” Norman Public Schools Superintendent Nick Migliorino said. “We’re going to do right by our students and right by our teachers, and we’re not going to have Bibles in our classrooms.”

Walters slammed the superintendents refusing his order as “woke administrators” and urged them to move to California because he would not allow them “to indoctrinate students in Oklahoma.” Of course, he said this as he literally insists they teach the Bible to students in Oklahoma. Walters claims he will move to enforce his mandate, which will spark more litigation.

Ryan Walters, Oklahoma Superintendent of Public Instruction (right), bows his head in prayer along with other members of the state’s Board of Education during an official meeting on April 12, 2023. (Sue Ogrocki/Associated Press)

Walters argued his order is necessary because the Bible “had been removed from classrooms, and we’re saying, listen, we’re proud to be the first state to bring it back.” He added, “Until the 1960s, if you walked into a schoolhouse, you were going to see the Bible.” His argument alludes to the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court case Abington School District v. Schempp, where the justices ruled against compulsory Bible reading in public schools. That case is frequently attacked today by those who espouse Christian Nationalism, often depicted as one of the cases in that era that “kicked God out of schools” (which makes God seem not-so-Almighty if nine people in black robes can keep God out of a building).

Walters isn’t alone in wanting to put the Bible in public schools again. For instance, Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, who’s been advocating for Christian Nationalism, argued last month, “We ought to take the Pride flag out of schools and put the Bible back in.” And many are hoping for a court challenge to undo the 1963 case. Walters has praised former President Donald Trump for putting new justices on the court that Walters believes will back his effort to return the Bible to public schools.

Although lots of people talk about compulsory Bible reading being ended in 1963, few consider how that practice started. As a state education leader wants to turn back the clock to once again force the Bible into classrooms, it’s worth considering why lawmakers pushed this before. For that story, we must travel back not to 1963 but to 1913. So this issue of A Public Witness looks at the creation of the law that eventually led to the Supreme Court’s case on the Bible in schools to determine what it teaches us about the Christian Nationalistic motivations behind efforts today to put the Bible back in classrooms.

How a Bible Becomes a Law

During the 1913 legislative session in Pennsylvania, freshman state Rep. John Fleming Lowers introduced a bill to require each public school classroom in the state open with the reading of 10 verses from the Bible. Elected as a Republican for that single two-year term, he didn’t seek reelection. Decades later he ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. House as a Democrat.

The bill had actually been introduced by a different lawmaker, Rep. William Ward, the previous two terms, in 1909 and 1911 (the state legislature only met every other year back then). Introduced late in the 1909 session, it didn’t move in the House before the session ended. In 1911, the bill passed the full House and moved over to the Senate, where it sat until it once again died as the session gaveled to a close. But the proposals sparked public interest and advocacy.

With Ward no longer in office, Lowers sponsored the bill at the heart of the Supreme Court case. The bill would require the teacher (or someone designated by the teacher to be in charge) start “each and every public school upon each and every school day” by reading “at least 10 verses from the Holy Bible … without comment.” The bill also directed school districts to remove any teacher who failed to follow the mandate.

Among the key groups organizing support for the legislation were several “patriotic” organizations (i.e., anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, antisemitic groups promoting “Americanism”). While religious ideals (and religious bigotry) mixed in the purposes of those groups, only one significant religious group publicly pushed for the Bible bill. It wasn’t a denomination, though the group activated many local clergy to speak out for the legislation. The National Reform Association wanted to see the Bible in public schools across the country. Although nationally focused, their headquarters and staff were in Pennsylvania, giving them a larger influence in the Keystone State.

The group was birthed during the Civil War to make the nation more Christian. Its original, wordy name captured its primary goal: National Association to Secure the Religious Amendment of the United States Constitution. The Confederates had put God in their constitution, so some wanted the Union to do so as well. The push during the Civil War continued afteward for a couple decades to alter the Constitution’s preamble to fix the problem of the so-called “godless” U.S. Constitution. The Presbyterian layman leading the effort wanted it changed to read: “We the People of the United States, recognizing the being and attributes of Almighty God, the Divine Authority of the Holy Scriptures, the law of God as the paramount rule, and Jesus, the Messiah, the Savior and Lord of all, in order to form a more perfect Union…” Although they gained support from some members in Congress in the latter half of the 19th century, none of the proposals ever passed.

Eventually, the group changed its name to the National Reform Association. Although still wanting to mark the U.S. as “Christian” in the Constitution, the NRA name also represented a broader Christian Nationalistic agenda. A key priority that soon emerged was pushing for the Bible to be read in more public schools. State court rulings in Ohio and Wisconsin in the late 19th century particularly helped inspire such advocacy and also gave rise to NRA rhetoric in the late 1800s and early 1900s about an alleged secular push to drive the Bible and God out of schools (showing there is indeed nothing new under the sun).

As the first decade of the new century ended, the NRA particularly focused on requiring the Bible in Pennsylvania schools. Although most schools in the commonwealth already used the Bible in some way, it had been a local decision since the creation of public schools in Pennsylvania in 1832. The NRA wanted it to be compulsory.

A teacher holds a Bible during an elective high school course on the Bible at Woodland High School in Cartersville, Georgia, on Oct. 20, 2011. (David Goldman/Associated Press)

During a 1910 NRA meeting, longtime NRA leader and Presbyterian minister Henry Minton insisted the U.S. was “a Christian nation” as he argued the Bible should be in every public school. He criticized a recent state Supreme Court ruling in Illinois that removed the Bible from schools, blasting it as “an outrage upon our history and an insult to the Christian people of this country.” He added that if states “refuse to allow Christian principles to be recognized and inculcated in the schools,” it will lead to “irreligion, paganism, and finally anarchy.”

A fellow Presbyterian minister and NRA organizer added at the meeting that the U.S. needs to mark itself as Christian in its Constitution, especially to push back against immigration. The first decade of the 20th century had brought a shift in who was immigrating to Pennsylvania, with a rise in newcomers from eastern and southern Europe instead of western Europe. Instead of Protestants, the new immigrants were largely Catholic, Jewish, or Orthodox.

“Immigration is foreignizing our national life. The Bible made America, and the only way to make Americans is with the Bible,” argued Rev. J.S. McGaw, “The man who would remove it [from schools] fires on the flag. It requires an infidel or an atheist to make an anarchist. If the reading of the Bible is unconstitutional in any state, then that state and this nation need a new Constitution.”

While the speakers often talked about the supposed threat from atheists, other key targets were Jews and Catholics. The NRA called for “Christian patriots” to help them protect the U.S. as “a Christian nation” after a group of rabbis in 1909 argued against the use of the Bible in public schools. And Minton declared during the 1910 NRA meeting that “there are today a number of forces greatly imperiling our national Christianity,” thus requiring “a revival of national religion.” Detailing the threats, he added: “Neither Judaism nor Roman Catholicism can dominate in America and she be Christian.”

The group cultivated strong political ties to push its agenda, with speakers at its events in Pennsylvania including the governor of Kansas in 1912 and a former New Jersey governor in 1913. During a meeting in 1911, the group elected six vice presidents, including a U.S. congressman from Alabama and former governors of North Carolina and Virginia. At that 1911 meeting, the group also announced it would be organizing to push legislation in Pennsylvania and elsewhere to mandate the reading of the Bible in public schools.

At the start of 1913, the NRA held a Christian Citizenship Conference to lay out its agenda for Pennsylvania’s legislators. The list included “the Bible in our public schools,” along with an anti-polygamy constitutional amendment, efforts to shut down saloons, “Christian laws governing marriage and divorce” (by reducing the grounds by which one could file for divorce), Sabbath Day observance, “a revival of national religion,” and “the nation’s allegiance to Jesus Christ the king.”

The Pennsylvania Capitol in Harrisonburg in 1907, a year after its completion. (William H. Rau/Public Domain)

Rep. Lowers quickly put the Bible in public schools bill into action. Introducing it on February 3, Lowers argued the King James Version of the Bible was “the Bible of our American forefathers” and had “influenced American ideals in life and laws and government.” Thus, he insisted the KJV is the “one universally accepted Bible open to all who wish to read it.” That claim ignored the fact that Jews and Catholics used different canons and translations.

“The Bible itself is not sectarian. It only became so by interpretation,” Lowers added, offering his interpretation on biblical debates. “It itself is free from sectarian bias. Its pages are open to all people and it is known all over the civilized world as ‘the Christian Bible.’”

During a House floor debate, Lowers went even further in his remarks, showing his anti-immigrant bias. He argued his bill was needed since “the children who come from other shores lack the moral and educational training necessary to become a part of this great country of ours.” He claimed that in communities with lots of new immigrants, one finds “nothing but filth and squalor and an absolute absence of any moral training.” Thus, he believed it was necessary for the commonwealth to teach the Bible because he didn’t expect the children to get it at home. Although some lawmakers argued against the bill, including a Catholic legislator who complained about the effort to force a Protestant text on his children, the bill passed the House 149-29.

As the bill moved to the Senate, it gained more attention — in part as some pastors encouraged people to support the bill. During a state senate judiciary committee hearing in April, witnesses included the state NRA leader and representatives from several patriotic groups. More than 300 people arrived to support the bill, filling the room to standing capacity. Only one person testified against the bill: a rabbi.

Despite the vocal support for the bill, it ran into opposition from Catholics. That led to the bill initially appearing dead in committee. But it was resurrected two weeks later after Lowers made a deal with another lawmaker. Lowers voted for — and moved other representatives to vote for — a bill to give Catholic bishops legal control over the real estate in their dioceses (a move made so the local Catholic Church could control new Catholic immigrants from eastern Europe). In return, Catholic opposition to the Lowers bill ended, thus allowing the passage of the bill mandating reading from a Protestant version of the Bible. This Catholic-Protestant compromise was called by one state reporter at the time “perhaps the strangest [deal] in the history of the Pennsylvania legislature.”

Only one senator, a Quaker, voted against the bill in committee. After the deal, both bills passed the full Senate. Republican Gov. John K. Tener signed them both on May 20. With that, Pennsylvania joined Massachusetts as only the second state to require daily Bible reading in public schools.

As the school year started that fall, the NRA announced it was tracking compliance with the new law and was “inaugurating a nationwide campaign to secure the kind of legislation that has been secured in this state, throughout every state in the nation.” During the group’s 1913 convention in Pittsburg, an NRA leader reported on the progress of getting the Bible read in public schools across the country, moving from 4,461 schools in 1900 to 28,021 in 1910. Hoping to grow that number, the NRA launched a campaign to raise $25,000 (equivalent to $785,000 today) to push for such legislation across the country.

The next year, the NRA appointed a seven-person committee to lead its national campaign to get laws like the Pennsylvania one passed in other states. Included on the committee was Rep. Lowers, fresh off his victory in the Pennsylvania legislature the previous year. Even after his one term in office, he continued to promote this effort. For instance, in 1915 he spoke at a special public high school event at a local Methodist Episcopal church where he was billed as the author of the Bible bill and presented the school with a Bible. Meanwhile, another 10 states made Bible reading compulsory in public schools.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

1913 vs. 1963

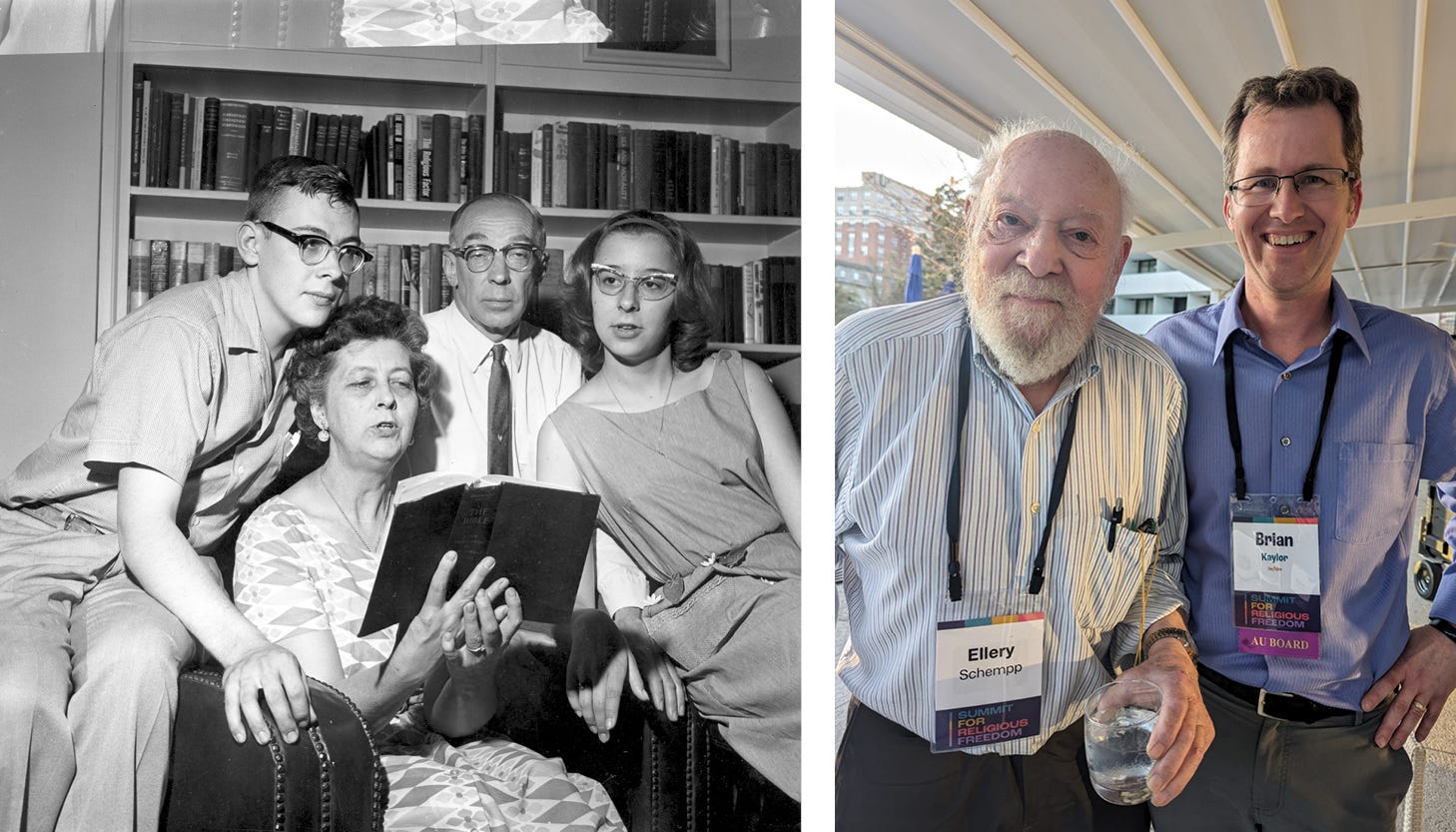

After decades of Pennsylvania school children listening to their teachers read Bible verses every day, the practice unraveled. In 1956, 16-year-old Ellery Schempp opened a Quran to read silently during the Bible time. After he was disciplined for that protest, his parents, Edward and Sidney Schempp, filed a suit the next year on behalf of their three children who attended public schools in Abington Township. As Unitarians, they rejected many of the Christian doctrines highlighted in the chosen daily readings. The schools were also having the students recite in unison the Lord’s Prayer after the Bible reading each day.

After a district court ruled for the Schempps and struck down the 1913 law, the state legislature amended the law in 1959 to allow children to be excused from the Bible reading time. But that was not enough to stop the litigation. On June 17, 1963, an 8-1 decision from the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the state. The 1913 law was dead. The majority opinion justified the move in light of constitutional protections of religious liberty.

“This freedom to worship was indispensable in a country whose people came from the four quarters of the earth and brought with them a diversity of religious opinion,” Justice Tom Clark wrote. “It is no defense to urge that the religious practices here may be relatively minor encroachments on the First Amendment. The breach of neutrality that is today a trickling stream may all too soon become a raging torrent and, in the words of Madison, ‘it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties.’”

Although the justices didn’t unpack how the 1913 law came to be, it’s worth remembering today as some want to undo the 1963 ruling. Compulsory Bible reading in public schools came during a time of demographic changes that brought fears that White Protestant Christianity was losing its status in society. The record shows that nativism, ethnic prejudice, and religious bigotry served as primary motivations for the legislation. Concerns expressed by religious minorities — including Jews, Catholics, and Quakers — were ignored. And a key group mobilizing support made it clear they wanted to codify Christianity and mark the U.S. as officially “a Christian nation.”

When I spoke with Ellery Schempp earlier this year during the Summit for Religious Freedom, he told me it was disappointing to see us dealing with the same issues he thought had been resolved decades ago with his family’s case. But here we are still debating what type of nation we want.

Left: Sidney Schempp reads from a Bible as her son Roger, husband Edward, and daughter Donna listen in their Roslyn, Pennsylvania, home on June 18, 1963, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in their favor. (Associated Press). Right: Ellery Schempp with Brian Kaylor at the Summit for Religious Freedom in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 2024. (Word&Way)

What Ryan Walters is pushing in Oklahoma may seem like just a trickling stream. But the full agenda of those pushing Christian Nationalism proves that, like the National Reform Association more than a century ago, they want a raging torrent. Thus, we face a choice today of which precedent we want to follow. Do we want a 1963 protection for the religious liberty rights of all? Or do we want a 1913 bigoted, Christian Nationalistic attempt to codify one version of Christianity? May we learn from history so we don’t repeat the same mistakes.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor