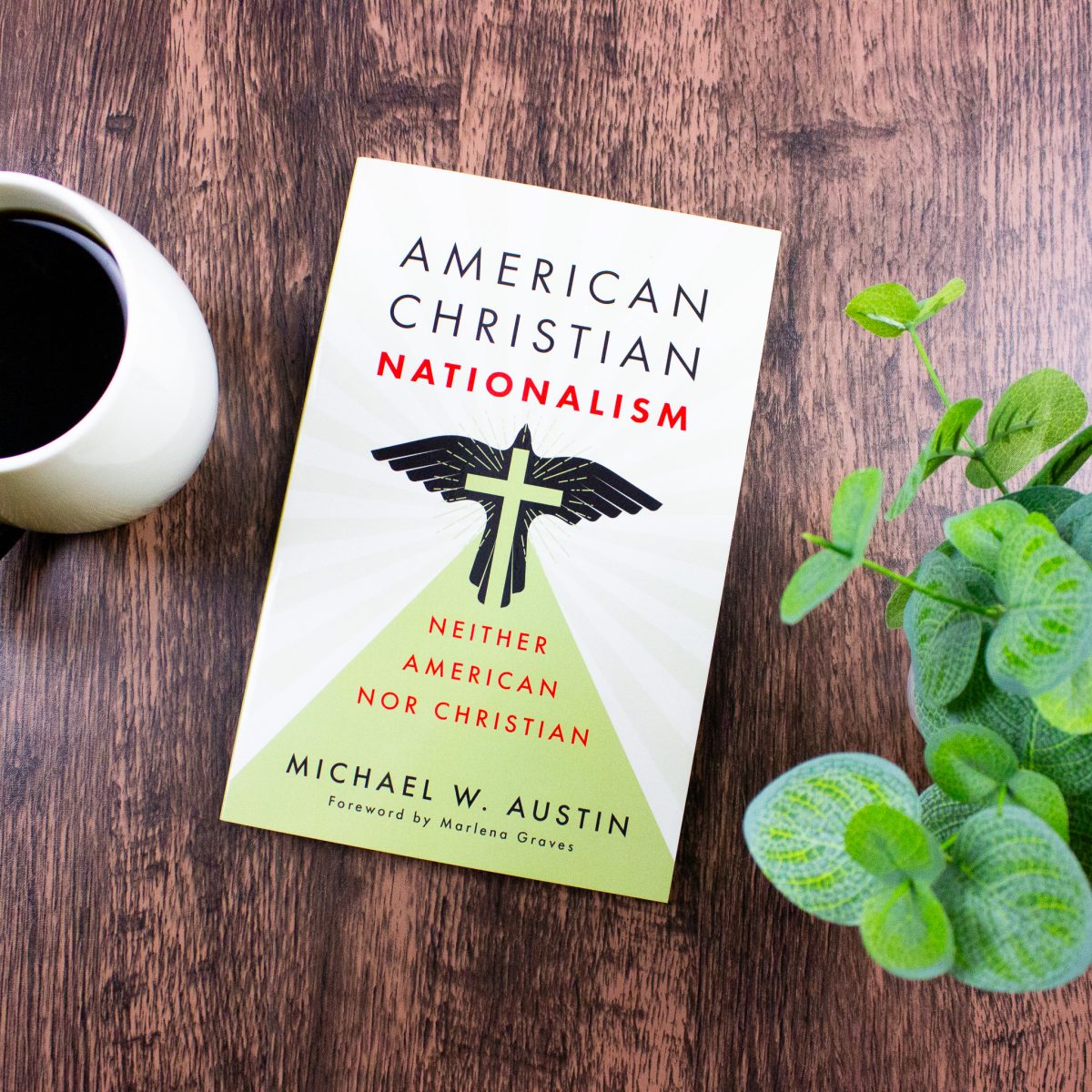

AMERICAN CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM: Neither American nor Christian. By Michael W. Austin. Foreword by Marlena Graves. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2024. Xii + 92 pages.

I am posting this review of American Christian Nationalism on the day that the United States holds an election that includes an important, and perhaps pivotal, presidential election. It is an election in which some partisans reflect strong Christian Nationalist tendencies. There have been significant numbers of books and articles published in recent years that have explored the impact of Christian Nationalism on the nation’s political life. While forms of Christian Nationalism have existed in the United States since colonial times, it has taken on new life in recent years as it has become a potent force within one particular political party. While the candidate for President who is backed by many Christian Nationalists doesn’t exhibit Christian values, he has embraced their cause as he pursues his own agenda. That is the situation facing the United States on November 5, 2024.

Robert D. Cornwall

One of the primary questions that emerge from discussions of Christian Nationalism is whether, on one hand, it is Christian and, on the other, whether it reflects American values. I have read several excellent books that discuss this amorphous movement in American political life. These resources help readers distinguish between patriotism and nationalism, as well as discuss the relationship of the movement with Christianity itself. These books and articles point out that many proponents of Christian Nationalism, at least in its more extreme forms, seek to gain dominion over the government and the various spheres of American life. Many of us have concluded that this movement poses a danger to both the church and the state.

Michael W. Austin has written what I believe is a perfect book, a book that carries the title American Christian Nationalism: Neither American nor Christian, that speaks directly to the concerns many Christians have about this movement. What makes this the perfect book is that many who struggle with this issue are not going to read a two-hundred-plus-page book on the subject. This is where Austin’s American Christian Nationalism makes its contribution. At just over eighty pages in length, this book covers the bases and uncovers the dangers posed by Christian Nationalism to both church and state.

Michael Austin serves as the Foundation Professor of Philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University as well as Bonhoeffer Senior Fellow of the Miller Center for Interreligious Learning and Leadership of Hebrew College. He has published twelve books including one that discusses Christianity and conspiracy theories. Thus, he is well-equipped to handle this issue facing the Christian community at this moment. Although this is a very short book, Austin uses the book to provide a “critical introduction to American Christian Nationalism,” describing what it is and why it is a matter of concern (p. xi). Thus, it is aimed not at the scholar but the general public, especially the Christian public, who aren’t sure what this Christian Nationalism is. Again, it’s not patriotism.

Austin begins the discussion in Chapter 1 by “Defining American Christian Nationalism.” He reminds us that this isn’t a new movement but has been with us since the beginning of the nation. However, it has become more of a matter of concern in recent years. He points out that American Christian Nationalism has several features. First, “American Christian Nationalists believe America was founded as a Christian nation.” This is a common refrain heard from the lips of proponents. However, Austin writes that while the founders often used religious language to describe their vision of the nation they did not explicitly describe the United States as a Christian nation. Secondly, they “believe the government of the United States should promote a particular kind of Christian culture (p. 8). Here is where things start to go in a dangerous direction. This is not just generic Christianity that has defined American civil religion. Instead, it is usually a very narrow and conservative form of evangelicalism. Third, they “believe that American Christians should pursue political and cultural power in order to take dominion over America.” Again, the issue isn’t Christian participation in political life. Rather, it’s a desire to achieve power and dominion over every sphere of life in the country. Fourth, they “believe that American Christians should prioritize American interests over the interests of other nations.” While it makes sense that the United States government would prioritize the needs of American citizens, that doesn’t mean the United States doesn’t have a responsibility to others outside the nation. Another move that gets us in trouble is the idea that “American Christian Nationalism fuses the American and Christian identities of its adherents” (p. 11). Again, this isn’t just another form of civil religion, it is the equation of church and nation. When the two are fused, then to be American is to be Christian. Therefore, if you’re not a Christian you must not be an American. As Austin points out, that doesn’t sound very American.

The second chapter is titled “American Values and Christian Nationalism.” One of the helpful elements of this book is that Austin addresses Christian Nationalism from both an American and a Christian perspective. I appreciate the fact that he opens this chapter by quoting Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Colossus,” which is mounted on the Statue of Liberty. This is a message of welcome offered to immigrants and refugees. It is a reminder that the United States is composed largely of people whose ancestors came here from elsewhere. So, even as some Americans embrace anti-immigrant sentiment, we would be wise to remember our ancestry. That is because, unless we happen to be Native Americans or descendants of African slaves, our ancestors came here from elsewhere. Perhaps you the reader hail from another nation. As to the nature of these American values that are at stake with Christian Nationalism, Austin speaks of three qualities. These include liberty, equality, and service. These three values define what is good about America. These are the qualities that define what it means or should mean, to be American. While the United States has never quite lived up to these values, they define what Americans should aspire to. Christian Nationalism, in its desire to gain power over others, tends to undermine these values.

Not only is Christian Nationalism a threat to American values, but it also poses a threat to Christian values. So, Austin writes in Chapter 3 about “Christian Values and Christian Nationalism.” In this chapter, Austin points us to the witness of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, whose resistance to Hitler’s schemes has been widely celebrated. Bonhoeffer was clear that loving Jesus is not the same thing as loving one’s nation. So, what are the Christian values that Austin believes are at stake? He begins by identifying the problem of idolatry. He suggests that too often Christian Nationalism veers into idolatry (as seen in the fawning over Donald Trump). He writes that Christian Nationalism distorts Christian faith by undermining the message of Jesus. Since taking dominion over the nation is often part of the premise of Christian Nationalism, Austin reminds us of our calling to imitate Jesus, who didn’t seek dominion over nations. He also reminds us of our calling to make disciples, which is undermined by the political dimensions of Christian Nationalism. Thus, “discipleship happens in and through the church, not the government” (p. 49).

If Chapter 3 focuses on Christian values, Chapter 4 focuses on Christian virtues. That is, when it comes to being a Christian, character counts. Unfortunately, the embrace of Christian Nationalism has undermined and contradicted Christian virtues, such as humility. With that in mind, Austin emphasizes three virtues: faith, humility, and love. When you seek dominion over others, seeking to control their lives, these virtues get tossed aside. Christian Nationalism is rooted in fear of the future, thus undermining faith in God. Humility is expressed in service to others, while Christian Nationalism emphasizes a form of pride that suggests Americans are better than others. Finally, Christian Nationalism undermines the virtue of love. Austin writes that to be a person of love is to have “the disposition to will the good of others” (p. 49). Christian Nationalism asks the question, who is my neighbor, and defines neighbor narrowly. Thus, Christian Nationalism violates both the Great Commandment (love God) and the Great Virtue (love your neighbor).

Finally, Austin draws on Martin Luther King’s vision of the Beloved Community in his conclusion to this brief look at Christian Nationalism and its implications for church and state. What he does here is remind us that our calling as Christians is to pursue the Beloved Community. The Chrisitan’s calling is not to build a Christian nation where Christians control and dominate all aspects of society. Rather, to be a Christian is to move toward living in the Beloved Community. His point here is not that Christians should refrain from participating in politics and government. Instead, he seeks to remind us of our ultimate destiny, which doesn’t involve taking control of the American government and culture. The vision here is one of inclusion not exclusion, which is one of the principles inherent in Christian Nationalism. Austin is convinced, rightly so in my mind, that we’ll never truly inhabit this beloved community in this life, but we can move toward it. He writes: “Let’s try to create a world, or at least try to move closer to a world, where it is simply us, not us versus them or even us and them.” Only us, as the song says” (p. 78). With that, I heartily agree.

Michael Austin’s American Christian Nationalism doesn’t offer an exhaustive examination of Christian Nationalism. Several excellent books offer that kind of resource. What Austin does is provide the reader with the kind of book that can be read in short order, while gaining a rather expansive vision of the dangers of Christian Nationalism while holding out a vision of the Beloved Community. Austin offers this vision as a counter to the destructiveness of Christian Nationalism to both church and state. In essence, Austin’s American Christian Nationalism is the perfect book to hand off to someone who might be attracted to dimensions of Christian Nationalism but doesn’t have a sense of the downside of taking that route. It can serve as an excellent primer for everyone in the church who seeks to be a productive citizen and a follower of Jesus.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.