NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

During a recent legislative debate on the floor of the Missouri Senate, a Republican lawmaker criticized someone he thinks isn’t a real Baptist. Me.

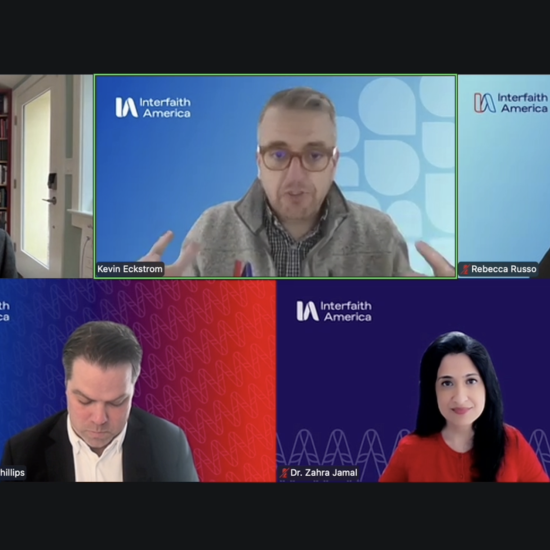

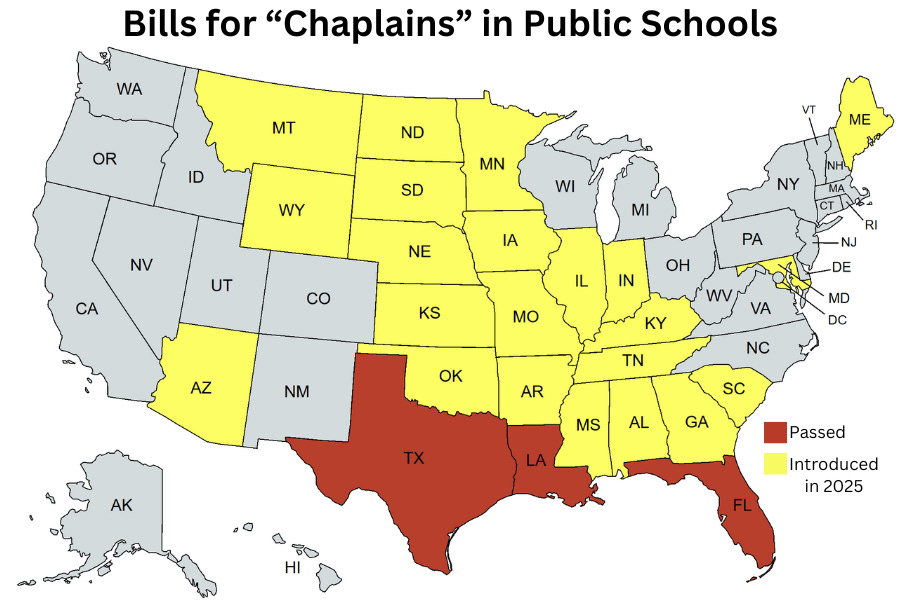

The moment occurred during discussion on the Senate floor about a bill pushing spiritual “chaplains” in public schools. Texas passed such legislation in 2023. That inspired copycat bills in 15 states the next year, including Florida and Louisiana passing such bills. Now, like a bad weed, it’s spreading as lawmakers in at least 22 states have sponsored this legislation already this year.

I testified against the idea last month during a hearing in the Senate Education Committee. Despite my brilliant arguments, the committee passed the legislation anyway. That led to the consideration of the bill by the full Senate.

Democratic Sen. Maggie Nurrenbern, who is Catholic, expressed concerns about the bill during the Senate debate. A member of the Education Committee, she had previously heard the testimony for and against the bill. As she explained her concerns to her colleagues, she dialogued with one of the two senators who filed the legislation, Republican Sen. Mike Moon. One of the leading proponents of Christian Nationalism in the Missouri legislature, Moon is a member of a large, fundamentalist Baptist church that’s dually aligned with the Baptist Bible Fellowship International and the Southern Baptist Convention. As they talked, Nurrenbern noted the religious opposition to the bill, leading to an exchange where they cut in a bit on each other:

Nurrenbern: What I saw, Senator, was so many trained chaplains that have signed onto letters in opposition to these bills. We have ministers who came before us in the committee… Moon: I saw that. Nurrenbern: …to say that they’re adamantly opposed to any of this legislation. Moon: He claims he’s a Baptist minister, but I don’t think he’s part of a Baptist church and he’s not a preacher. So that’s kind of interesting. He’s testified for a lot of different bills over the years and… Nurrenbern: Yeah, I’ve heard him on a lot of different bills and I always appreciate his perspective. But, Senator, I’m not only speaking about that individual; I’m speaking about others. I have multiple trained chaplains from Missouri who have also signed onto letters opposing chaplains in public schools.

I appreciate Sen Nurrenbern’s kind words about my testimony. And I was glad to hear how well she spoke during the one-hour-and-forty-five-minute debate about the bill on the Senate floor as she raised many of the issues I had expressed concerns about in the committee hearing.

But Sen. Moon’s comments took me by surprise. Seeing that the full Senate had, unfortunately, passed the bill (albeit with some amendments that made it less bad), I listened to the debate recording just to get a sense of the arguments in case the legislation gets a hearing in the House. Suddenly hearing an attack on myself was unexpected (although unnamed, I’m the target since I was the only Baptist minister who testified in that hearing). Even more so, I was stunned to hear that I’m not “part of a Baptist church” and “not a preacher.” That was news to me!

The Baptist church I’m a member of — and where my Word&Way office is — sits about three blocks from where Moon stood as he made his claims. Most Sundays (and Wednesdays) I’m at the church, where I co-teach a Sunday School class and play the cello in the church orchestra. The latter part means my regular attendance at the church is actually easy to document via the worship livestream!

As for the “not a preacher” part, I assume Moon was trying to say I’m not currently serving in a pastoral role at a church. That’s true. And I never claimed I was. At the hearing — which was recorded — I merely introduced myself as “a Baptist minister,” adding that “I lead Word&Way, which is a Christian nonprofit that’s been here in Missouri since 1896.” I didn’t claim to be a pastor, although I have served as the pastor of a Baptist church. I’ve also served on staff of another Baptist church, a local Baptist association (that includes part of Moon’s district), and a Baptist state convention. I also preach some Sundays at churches. Me not being a preacher would surprise the congregations where I’ve recently spoken, including Baptist, Disciples of Christ, Presbyterian, United Church of Christ, and United Methodist congregations.

Brian Kaylor preaching and assisting with worship in multiple churches over the last few months.

What’s really significant about Moon’s comments, however, is not the inaccuracy of what he said. Rather than addressing the merits of my concerns, Moon instead sought to define me as not really Christian enough to be listened to. With that, he amplified concerns that I and others have raised about the “chaplains” in public schools legislation in various states and about the Christian Nationalism of Moon and other lawmakers as they push such bills. So this issue of A Public Witness mounts a bully pulpit to warn about the dangerous Christian Nationalistic targeting of public schools.

Chaplains in Name Only

As I spoke to the Education Committee, I argued that the legislation was inaccurately framed. The sponsoring lawmakers claimed it “authorizes school districts and charter schools to employ or accept chaplains as volunteers.” But I noted that’s not true as it’s “a chaplain in name only” bill since “there aren’t actually requirements in the legislation itself about who can be a chaplain.” While the sponsors and witnesses for the bill had previously spoken about other types of chaplains — like in the military and prisons — I pointed out that those aren’t good examples to compare with this legislation. The chair of the committee even argued that the bill was about chaplains, not letting some street preacher come into schools.

“There’s actually nothing in this legislation that would prevent a school district from hiring that street preacher to come in and be the school chaplain,” I explained in response. “There are no requirements. They’re using the word ‘chaplain’ without any requirements for it.”

“A chaplain is different than merely a pastor or a volunteer Sunday School teacher or just a happy evangelist,” I added. “If we’re going to have a school chaplain program, let’s make sure we actually have some strong requirements about who’s a chaplain, other than they can pass a background check and they’re not a sexual predator. Those are great baselines for anybody walking into our public schools, but that does not make someone a chaplain!”

The proposed legislation didn’t have any standards beyond what it takes to get hired as a janitor — and even then, schools might expect someone to actually have previous janitorial experience. The state Department of Corrections, on the other hand, has requirements about education, experience, and religious endorsement to be a chaplain. Same with the military, whose requirements also include passing a military physical exam. Oddly, Moon claimed during the hearing that the proposal would require would-be chaplains to complete “an 80-hour training requirement” even though that’s not actually in the bill. It made me wonder if he’d read the bill, which he didn’t write as it’s instead being given to lawmakers by the National School Chaplain Association (more on them in a moment).

The lack of standards for who can serve as a chaplain leads to a second problem that I highlighted: “There’s also nothing in this legislation that would prevent proselytization.”

“What makes school different than military and the Department of Corrections and workplaces and even here with your own chaplain is we’re talking about minors. And so we have to be much more careful to make sure that we’re not violating … the rights of parents and their faith communities to be the ones that provide the spiritual care and nourishment and instruction that we want,” I explained. “As much as my son might claim that going to school is like going to prison, it is actually quite different. One, he gets to come home every day. He’s free to go to church on the weekend. So there are opportunities for spiritual care, which makes the chaplaincy program less significant than it is in a situation like the military or prison where people don’t have the opportunity to go to their local faith community whenever they want to for services. That’s why we help create chaplaincy programs in those places.”

After Texas lawmakers first passed a school “chaplains” bill in 2023, a diverse group of more than 170 chaplains in the Lone Star state signed a public letter urging school districts not to try the idea. This group of chaplains, which included dozens of Christians from various denominations, particularly pointed to concerns about proselytization of students against the wishes of parents.

“There is no requirement in this law that the chaplains refrain from proselytizing while at schools or that they serve students from different religious backgrounds,” the chaplains explained. “Not only are chaplains serving in public schools likely to bring about conflict with the religious beliefs of parents, but chaplains serving in public schools would also amount to spiritual malpractice by the chaplains. Government-sanctioned chaplains make sense in some settings, but not in our public schools.”

“We urge you to support religious freedom and parental rights by rejecting this harmful program to have government-approved chaplains in our public schools,” the chaplains added. “We believe that families, not the government, are entrusted with their children’s spiritual development.”

Several Christian denominations signed a similar letter in 2023 along with Jewish, Hindu, Sikh, and other groups. Organizations like the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and Pastors for Texas Children mobilized to get local school boards to vote against replacing school counselors with spiritual chaplains — and were successful in stopping this idea from actually being implemented in major districts.

Screengrab as Texas Democratic state Rep. James Talarico, a Presbyterian seminary student and former public school teacher, speaks at a Feb. 29, 2024, press conference at the Texas Capitol in Austin with chaplains and religious leaders about the problems with the push to replace school counselors with “chaplains.”

Concerns about proselytization by school “chaplains” are amplified because of the organization behind the legislation: the so-called National School Chaplain Association. As I noted in my testimony, the group has been clear about its goal of pushing unconstitutional Christian Nationalism in schools.

“On their website, they proclaim that ‘we are God’s representatives on school campuses.’ And Rocky Malloy, the leader of the organization, has said, ‘Good news, prayer is back in school. School chaplaincy is the first opportunity in 60 years to recover religious liberty lost when prayer was kicked out of school in 1962. … To make prayer in school a reality, please give your best gift to the National School Chaplain Association,’” I explained. “The stated public goals of the organization that wrote this legislation for Texas and then Florida and Louisiana, and now here, their goal is to push God and prayer in public schools. That concerns me a lot, especially when there are no guardrails in this legislation.”

Prior to my testimony, Sen. Rusty Black (the other lead sponsor along with Moon), mentioned in his opening remarks that he met with Malloy before filing this bill. And an out-of-state staff member from the organization also testified for the bill before I went to the microphone. So it was no secret who was behind the bill. Nor is it a secret what their true goals are since they said the quiet part out loud. This type of legislation is precisely about proselytizing in our public schools.

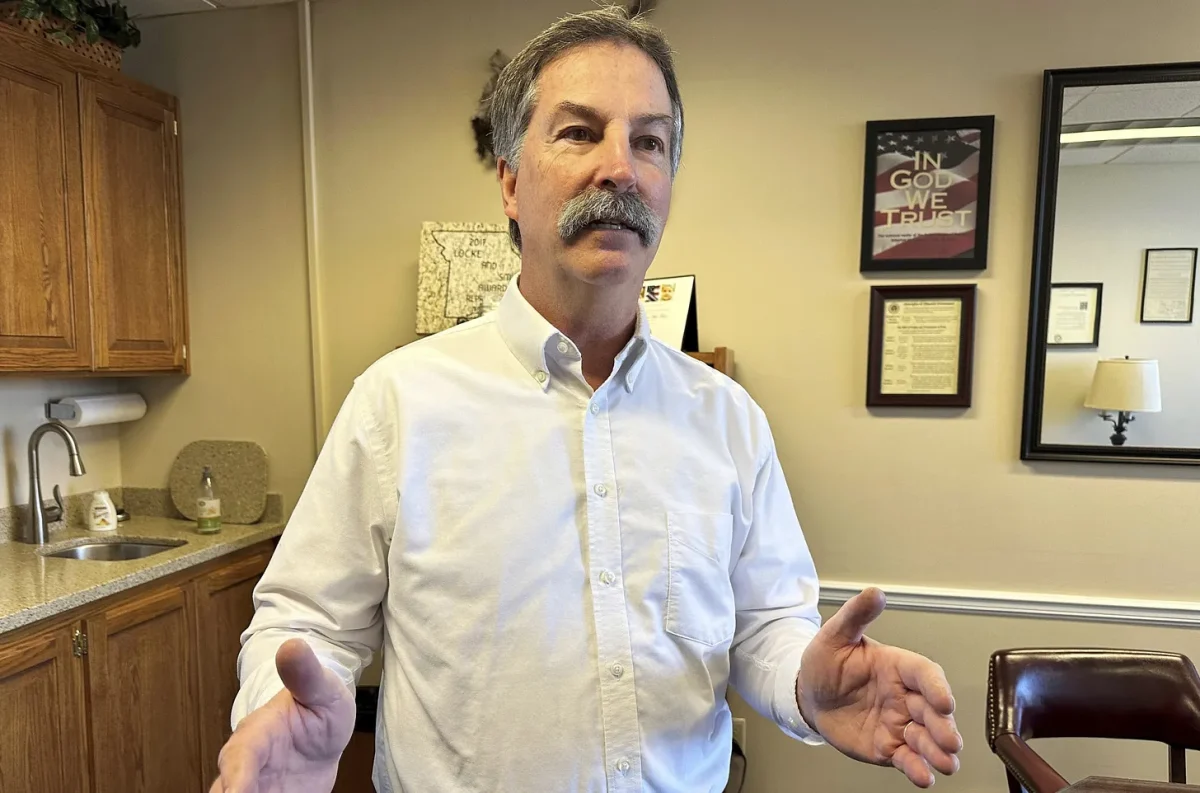

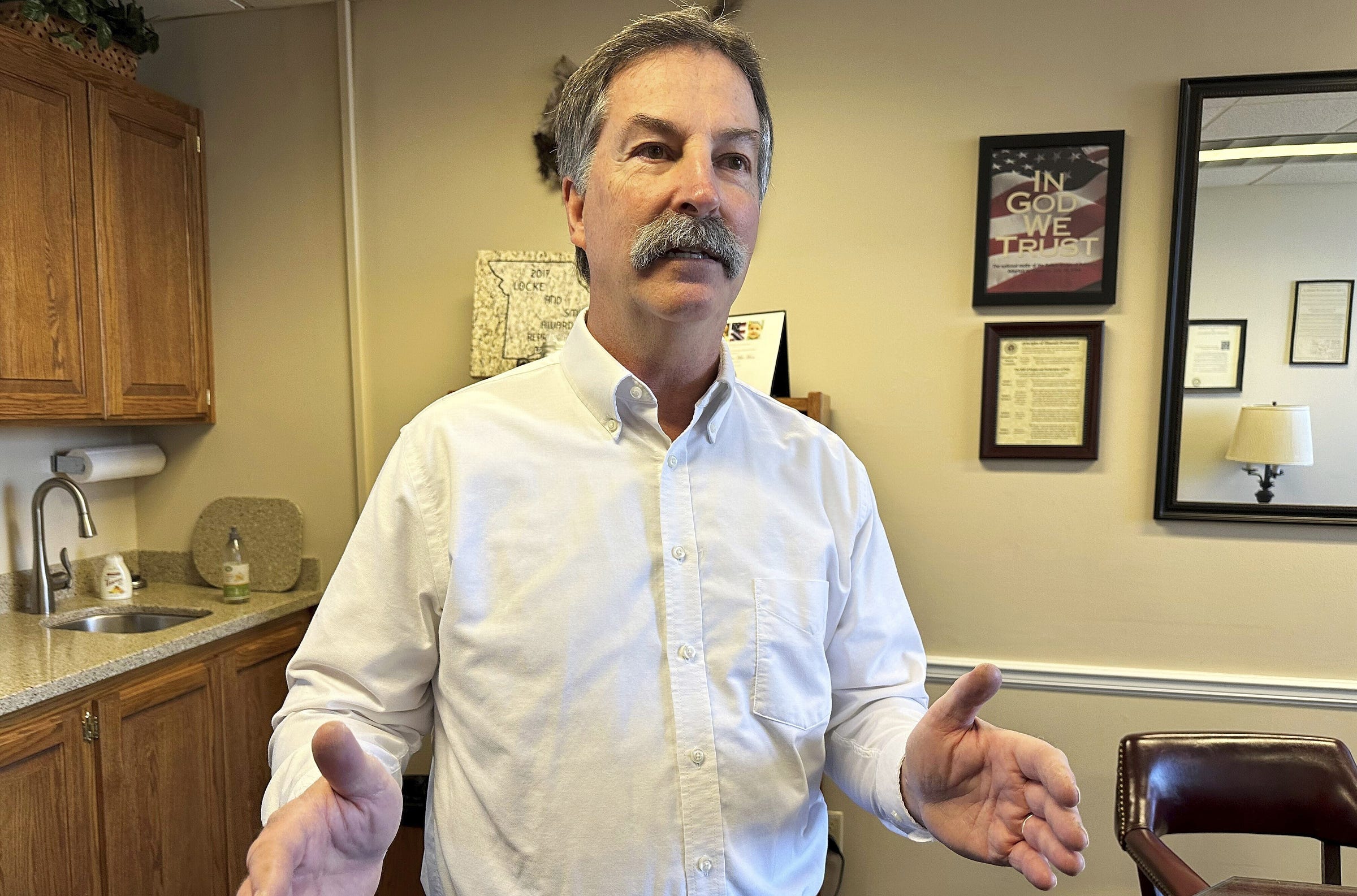

Missouri state Sen. Mike Moon in his state Capitol office — with an “In God We Trust” flag poster — in Jefferson City on Jan. 3, 2024. (David A. Lieb/Associated Press)

Help sustain the journalism of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Redefining Faith

Sen. Moon’s questioning of my Baptist credentials wasn’t the first time that’s occurred on the “chaplains” legislation. After my testimony in the Education Committee, the committee’s chair, Republican Sen. Rick Brattin, said he was “just perplexed by your testimony” and asked how “as a Baptist minister you’re against” this. I immediately noted that Baptists historically “believed in the separation of church and state, and I still hold to that.”

Brattin, a member of a politically active Southern Baptist church, quickly interrupted, “Where is that in the Constitution?” I’ve heard that line of attack before, so I told him I was happy to answer his question. I started noting that the phrase comes from a letter by Thomas Jefferson — who I assume Brattin had heard of considering a statue of Jefferson sat a couple hundred feet away from where we were talking at that moment in … checks notes … Jefferson City. I quickly noted that Jefferson wrote that to a group of Baptists because it echoed their language, but Brattin cut me off with another question. After addressing it, I returned to the church-state separation inquiry.

“The issue of coercion here is that if someone doesn’t have the right to say ‘no,’ then they don’t have the right to say ‘yes,” I said. “That’s why Baptists have believed in the separation of church and state — and it is a constitutional principle. It’s true, you won’t find the words in there. You also won’t find the phrase ‘religious liberty’ in the Constitution. But guess what? It’s a constitutional principle based on the First Amendment and Article VI, just like separation of church and state is a constitutional principle based on the First Amendment and Article VI.”

Unconvinced, Brattin ended our exchange where he started it: “No offense, I just, I’m blown away that you come and you actually testify as a Baptist minister. But I’ve been on this committee since I’ve been a senator and you’ve testified against any and every single religious anything put forth before this body.” As he tried to end my time, I quickly retorted, “I don’t want coercion in public schools. I’m consistent.”

A teacher holds a Bible during an elective high school course on the Bible at Woodland High School in Cartersville, Georgia, on Oct. 20, 2011. (David Goldman/Associated Press)

That line of questioning by Brattin — and the criticism from Moon — echoes what happened last week in Texas when a Baptist minister testified against a bill to require posting an edited version of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms.

“All Baptists are called to protect the separation of church and state,” said Rev. Jody Harrison, a retired hospital chaplain. “Is it really justice to promote one type of Christianity over all schoolchildren?”

Republican Sen. Donna Campbell argued during the hearing that they should pass the bill since “there is eternal life” and therefore “if we don’t expose or introduce our children and others to that, then when they die, they’ll have one birth and two deaths.” With that evangelistic goal in mind, she disagreed with Harrison. But the state senator went further by also telling Harrison what the minister should or should not believe.

“The Baptist doctrine is Christ-centered,” Campbell said with a harsh tone. “Its purpose is not to go around trying to defend this or that. It is to be a disciple and a witness for Christ. That includes the Ten Commandments. That’s prayer in schools. It is not a fight for separation between church and state.”

What Campbell did is akin to the comments of Moon and Brattin, and all three state senators demonstrate a problem with Christian Nationalism. They don’t seek to privilege all Christians but just a narrow slice of Christianity. Those who don’t fit that mold — even ministers and chaplains — are cast out as not the “right” type of Christian, scolded for what they believe, and questioned about whether they are even part of a church.

Christian Nationalism is not just a threat to nonbelievers and those of other faiths (though that would be enough of a problem); it also is a danger to Christians who hold beliefs outside of those in power or who dare to oppose governmental efforts to impose faith on others. It’s this Christian Nationalistic attitude that led some Republicans to attack the faith of Episcopal Bishop Mariann Budde for urging President Donald Trump to “have mercy” and that led Michael Flynn and Elon Musk to attack the religious credentials of Lutherans who care for immigrants and refugees.

Attempts by government officials to rewrite confessions of faith and excommunicate ministers or members are especially ironic when done in the name of pushing a “chaplains” bill that lacks standards for who can serve as a chaplain. They seem to assume it will be their version of Christianity that gets to proselytize in public schools. But the moment someone else gets one of those positions, the Christian Nationalist politicians will complain about another allegedly fake minister.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor