NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

“This was at the founding of our nation. So in order to run for office, you had to state this: ‘I do profess the faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ, his holy Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God blessed evermore. And I do acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.’ That was a requirement to hold office, that you had to give that oath in affirmation.”

That statement from Sen. Rick Brattin, Republican chair of the Missouri Senate’s Education Committee, came after he interrupted a Baptist minister testifying in opposition to SB 594 at a hearing on Tuesday (March 25). This proposed legislation would require public school districts in the state to display the Ten Commandments in every building and classroom.

The minister, W.B. Tichenor, responded: “Sir, to what you just read [from] Delaware — that meant no Jew could serve, that no atheist could serve, no Muslim could serve.”

“Certainly. Yeah, that’s right,” Brattin gleefully replied.

It is unclear if Brattin was pining for the days of religious tests for office in the early colonies — something the U.S. Constitution he swore an oath to uphold explicitly prohibits in Article VI — or if he was only making a broader point in support of a Christian Nationalist reading of history. But one thing was clear: He was going to hijack much of the time allotted for opposition testimony during this hearing.

“America was founded as a Christian nation,” Brattin declared. “[This bill’s] just declaring who we are as a nation. These are the standards in which we uphold and it’s God’s standard in which we, as a nation, uphold.”

The odd thing is that Brattin is not even the sponsor of this bill. That would be Missouri Republican state Sen. Jamie Burger. And when Burger was initially asked some basic questions about his bill at the start of the hearing, he seemed to not have many answers. He wavered on where he thought the posters should be hung as well as which version of the Ten Commandments should be used (even though the bill mandates language and placement). This is likely because this bill wasn’t written by Burger but is instead a copy of Ten Commandments legislation from Louisiana and Texas.

Sen. Rick Brattin (top left) listens as Rev. Michael Dunn (bottom right) testifies against the Ten Commandments in public schools bill while sitting next to the bill’s sponsor, Sen. Jamie Burger. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Despite being light on the details, Burger did make the case that this is a bill he feels very passionately about: “I honestly believe that when prayer went out of schools and religion was removed from schools, that’s when guns came in and violence came in.”

“You know one thing, I think when they talk about separation of church and state, I think they were talking about, ‘We don’t want a church ran by the state.’ That’s my feelings. That’s my interpretation,” Burger added, echoing the metaphor of a one-directional wall that has been prominently advocated for by U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson.

Bev Ehlen of Liberty Link Missouri PAC added her support to the bill: “When I learned about the history of our country, I realized that we became the freest, most benevolent, most prosperous nation in the world because our founding was based on God’s principles.”

“We have one suggestion to make,” Ehlen continued, “and this is a teaching moment here, because many times when the Ten Commandments were written … well, interpreted, I should say … revised, it was … we want to change it to, ‘Thou shalt not murder,’ because there’s a big difference between murder and killing.”

Presumably, this proposed change would be to align the text on the posters with current Christian Nationalist ideology, which shows high levels of support for death that (supposedly) isn’t murder, like capital punishment and any-means-necessary policing.

This hearing in the Show-Me State offers a window into larger political issues around the country as some conservative Christians are emboldened by a second Trump presidency to make attempts at enshrining their version of Christianity in the public education system. So this issue of A Public Witness takes you inside this contentious hearing in the Missouri Senate, offers context for Ten Commandments mandates spreading across the country, and highlights the strong Christian opposition to an attempted Christian Nationalist power grab.

Let My Posters Hang!

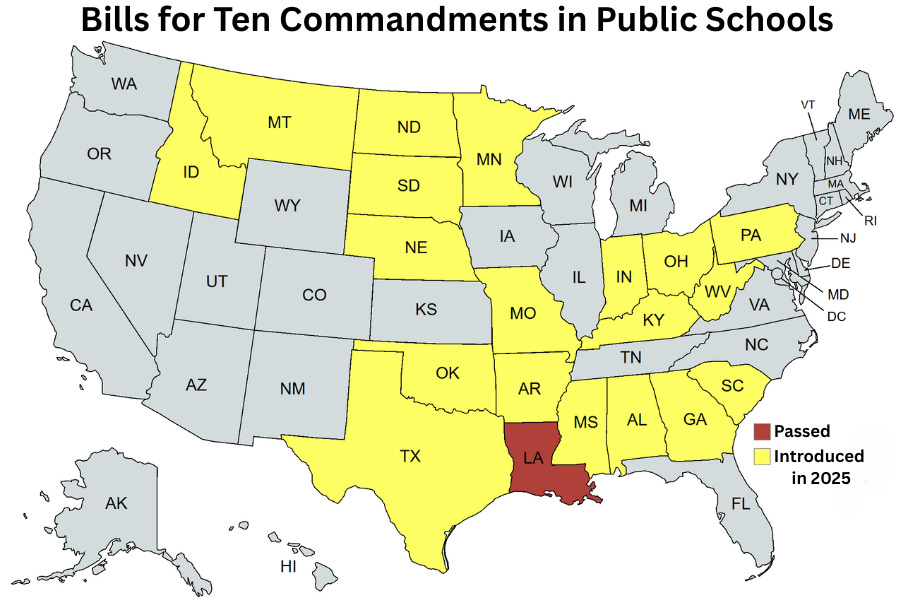

Bills aimed at getting the Ten Commandments displayed on posters by public schools have recently cropped up in more than 20 states. This practice was deemed unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1980 because it violates the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. However, a subsequent ruling written by Justice Neil Gorsuch in the 2022 case Kennedy v. Bremerton School District opened the door to reconsidering this by doing away with the precedent of a secular purpose test in favor of interpreting law by “reference to historical practices and understandings.”

This has directly resulted in a number of attempts to codify a specific strand of conservative Christianity within American education standards. Last year, Louisiana became the first state to require the Ten Commandments to be displayed in every public school classroom. The justification given by the sponsoring Republican lawmakers was that students need to understand the role of the Ten Commandments in American history. But despite this overt nod to Kennedy v. Bremerton, the law remains in legal limbo while it faces court challenges.

Just last week, the Texas Senate passed a similar bill to require the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms after previous attempts had failed. And earlier this month, Doug Mastriano proposed a similar bill in Pennsylvania. States such as Idaho, Indiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and West Virginia have all seen bills introduced this year that follow the same model.

Republican lawmakers in other states produced slight variations of this, such as an Ohio bill that would include the Ten Commandments as one of nine historical documents that must be selected for classroom display, a Kentucky bill that would allow but not require posting, and bills from Georgia and Alabama that would force schools to post the Ten Commandments in common areas throughout their buildings.

In some states, Ten Commandments bills have failed — even where Republicans control many of the levers of power. In Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, bills only managed to make it out of one legislative chamber. And the Democratic governor of Arizona vetoed comparable legislation last year.

One of the strangest details about each of these bills lies in what would actually appear on these Ten Commandments posters: promotional material from a film. Specifically, Cecil DeMille’s 1956 The Ten Commandments starring Charlton Heston. This edited version of the Ten Commandments, copied from granite monuments created for the movie’s marketing campaign, omits most of the biblical writing, only including 37% of the original text. It even directly changes some of the wording of its source, the King James Version, by removing references to “ox” and “ass” in favor of “cattle.”

As Tichenor brought up during his opposition testimony, “You will not find this copy of the Ten Commandments in any Christian translation of the Scripture.” And this doesn’t even account for the ordering and content differences in the Ten Commandments between Jews, Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians, as well as which English translation best represents the text.

These Ten Commandment bills are all related to a surge in other laws aiming to get Christian Nationalism into public schools. These have included attempts to require Bible readings, mandate prayer time, appoint “chaplains,” and order “In God We Trust” to be posted in classrooms. All of this is intended to crumble the (very much two-sided) wall of separation between church and state.

So Let It Be Written, So Let It Be Done

Brian Kaylor, president and editor-in-chief of Word&Way, added his testimony against the Missouri Ten Commandments bill during Tuesday’s hearing, arguing, “The idea that hanging up the Ten Commandments will stop school shootings is absurd. The Ten Commandments are not like a magical amulet or a good luck charm. If they were, we would not have seen mass shootings at Christian schools and even at churches. There are many ways we could reduce school shootings, but this is not it.”

“This is about the government taking sides on religion. … As was already noted, there’s a Ten Commandment monument just outside the Capitol on the grounds here — and that has not made the members inside this building follow all of those commandments,” Kaylor added. “[This bill] overreaches the state’s authority, using coercive state power to codify and teach sectarian faith. As Roger Williams said, ‘Forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils.’”

Listen to Brian Kaylor’s testimony:

A monument of the Ten Commandments at the Missouri Capitol in Jefferson City. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Michael Dunn, a Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) pastor on the executive board of Missouri Faith Voices, said in his testimony, “Is there anything more exemplative of something contrary to the faith of a generous God, and in my case, the faith of Jesus, than forcing the Ten Commandments on people?”

“And so if you’re purposeful — and I will say, if we are purposeful, because I feel like that, we’re all in this — about living out the spirit of the Ten Commandments, then we’ll say, ‘No, it’s not a smart bill,’” Dunn added.

Chairman Brattin, who previously criticized Kaylor for testifying against a bill to put “chaplains” in schools, aggressively questioned Dunn, who at one point had to correct the state senator for mistakenly claiming the bill was requiring the Ten Commandments to be hung at every school but not in every classroom.

High school student Calvino Hammerman, who spoke about his experiences going to a Jewish private school, added his testimony against the bill: “The Ten Commandments are not just a set of morals. The first five are explicitly about the Abrahamic God, the first one being that there’s one God. But my Hindu friends do not believe in this. But who is the government to tell them that that is wrong?”

“And this version of the Ten Commandments does not align with the one that I was taught. It’s similar, but it has key differences. Why should the government tell me which Ten Commandments, what it should be?” Hammerman asked.

Several pastors also attended to voice their opposition to the bill, including Episcopal minister Bill Nesbit, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) minister Alan Bailey, and Baptist ministers W. T. Edmonson, Melissa Hatfield, and Brittany McDonald Null. However, they and others who planned to testify against the bill were only allowed to turn in written remarks after Brattin ate up the time intended for public testimony. This came after he moved the bill to be heard last during a two-hour hearing with four bills under consideration.

After allowing the first affirmative witness to testify for over 11 minutes, Brattin then noted there were only 30 minutes left in the hearing and so encouraged people to “be as expedient as possible.” However, Brattin himself would speak for much of that remaining time. He interrupted the final opposition witness barely two minutes into her testimony to note there were only three minutes left in the hearing. Yet, after she quickly ended her testimony so others could testify, he then spent the remaining time of the hearing attempting to foment a debate about creationism and evolution — issues not even in the bill.

Brattin then announced that time for the hearing was over, prompting Kaylor to stand up and request from the audience that those who had been there for two hours to testify be given “30 seconds to introduce themselves.” Brattin yelled at Kaylor to “sit down” and gaveled the meeting to a close, thereby seeking to silence ministers there to challenge his Christian Nationalist ideology.

Though shocking, this was not particularly surprising given comments from Brattin earlier in the hearing: “Here we are having to pass legislation that just states that this is who we are as a nation. … I think it is a travesty to think that this is even a discussion.”

Clergy and other faith advocates who attended the Missouri Senate Education Committee to testify against the Ten Commandments in public schools bill. (Word&Way)

Later that day, Hatfield — one of the Baptist ministers who was denied the opportunity to speak during the hearing — took to Instagram to voice her testimony: “As a person of deep Christian faith, the Ten Commandments hold sacred significance for me. Though I often fall short, I strive to honor them in word and deed. As a minister and former public school educator, I firmly believe that we must keep our public schools welcoming to all students, regardless of their faith tradition. Public schools are among the few truly shared spaces in our society, and they must remain places where every child, parent, and educator feels equally safe, valued, and respected, regardless of the religious beliefs they hold or do not hold, or those of their family.”

“Furthermore, the teaching of sacred texts and theology belongs in our homes and houses of worship of Missourians’ choosing, not government-run classrooms. Our Constitution’s protection of religious freedom has allowed diverse religious traditions to flourish in this country, including my own Baptist tradition, which was founded partly on the belief that no one should be compelled in matters of faith. That conviction is rooted not only in history but also in God’s posture of freedom toward us,” Hatfield added. “I asked these Missouri senators to honor both our commitment to excellent public education and our cherished religious liberty by keeping our schools focused on learning, rather than legislating religion.”

As a public witness,

Jeremy Fuzy

By the way, if you’re a faith leader in Missouri, you can add your name to a letter opposing the bill mandating the Ten Commandments in public schools.