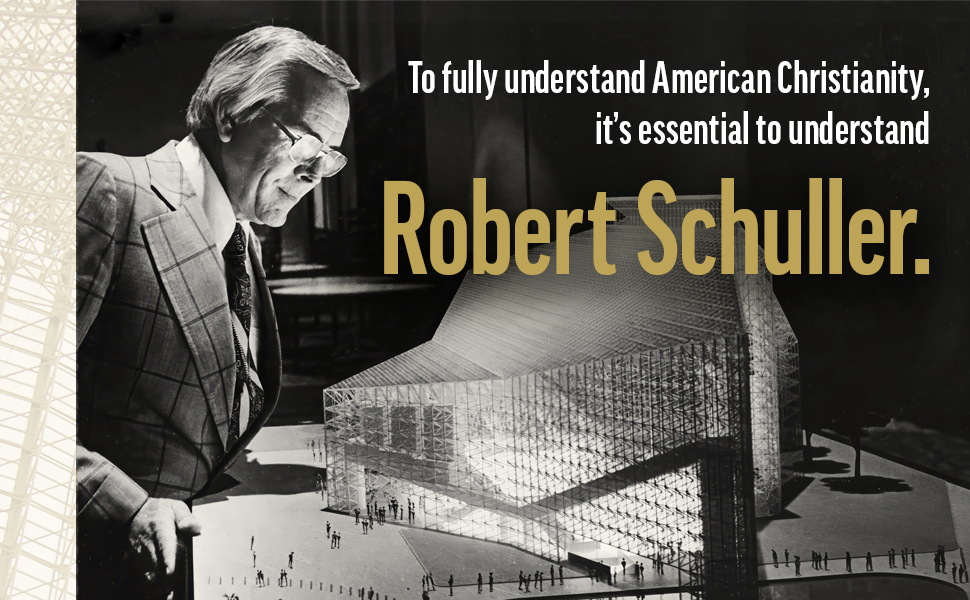

THE CHURCH MUST GROW OR PERISH: Robert H. Schuller and the Business of American Christianity. Library of Religious Biography. By Mark T. Mulder and Gerardo Martí. Foreword by Richard J. Mouw. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2025. Xiv + 327 pages.

In an age when most religious entities seem to be experiencing decline in numbers and influence, the pressure to resist this tendency and grow one’s community of faith is enormous. It is something that most of us who are members of the clergy feel in our bones. Except for the few brave souls who feel called to help congregations die, few of us want to be the pastor who oversees the closure of a ministry. There are plenty of voices that promise to help us reach the goal of expanding ministries and growing congregations. Unfortunately, despite hard work and commitment, most of us fail to achieve the goal of creating thriving, growing congregations. Yes, there are stories of success, but often it involves being in the right place at the right time. Such is the story of Robert H. Schuller, who is best known for building the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California. Schuller embraced the message of possibility thinking and offered his audience a theology of self-esteem. Schuller was a great success. He built a magnificent empire. However, in the end, the fall was dramatic.

Robert D. Cornwall

Schuller believed that, as the title of the biography written by Mark Mulder and Gerardo Martí suggests, “The Church Must Grow or Perish.” Schuller’s story might serve as a cautionary tale to others who might seek to pursue a vision of the church along the lines Schuller set out. This biography, The Church Must Grow or Perish, is an important read. The authors are both sociologists by training. Mulder is professor of sociology at Calvin University, while Martí is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Sociology at Davidson College and the current president of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion.

Although Robert Schuller’s fame might be fading in some circles, he remains an important figure in the history of American Christianity in the second half of the twentieth century. While his name might be well known for being the builder of the Crystal Cathedral and the star of the Hour of Power TV show, the question is, who is this man who reached the heights of religious success? What might we learn from his story that can help us proceed into the future?

I came to this biography with great interest. That is because I attended worship services at the Crystal Cathedral as well as at least one of its big productions. I think it was “The Glory of Christmas,” though it could have been “The Glory of Easter.” I also have a friend from my seminary who was once a member of the pastoral staff at the Cathedral. So, I have experienced at least elements of Schuller’s ministry. While the Cathedral was an impressive building, and its ministry was extensive, I always had questions about the theology that went with it. As a pastor, I wrestled with Schuller’s teachings about the church being a business. I wondered whether his possibility thinking might lead to shallow forms of the faith. So, I watched with interest as his empire collapsed, in large part because he couldn’t let go of the reins before it was too late. I had an inkling of who Schuller might be due to my contacts with people were close to the Cathedral, but in reading this biography, I gained considerable insight into the man and his enterprise. What we read here might be a cautionary tale for any would-be celebrity pastor, or even a small church pastor who might want to build an empire.

So, who was Robert H. Schuller (1926-2015), the proclaimer of possibility thinking? Where did a come from? What were the influences on his life? He was, in a way, a television evangelist, but of a different kind. He wanted to disassociate himself from the typical TV evangelist, especially the ones who experienced sexual and financial scandals. There was a reason why he was different from his competitors. For one thing, Schuller was an ordained minister in a mainline Protestant denomination, the Reformed Church in America. This largely Dutch Reformed tradition claims to be the oldest American denomination. Even if he lived on the edges of the denomination, it did serve as an anchor. He was also quite cognizant of the scandals that plagued many of his competitors. Therefore, he made sure that he did not put himself in that kind of situation. His vice, as we learn, was with food and his struggle with his weight. Ultimately, he was a builder. When he moved to California in the mid-1950s, he began his ministry by renting out a drive-in theater on Sunday mornings, catering to a car-centered population in Orange County. While Schuller would cater to folks who enjoyed worshipping from their cars, his experiment with a drive-in theater would lead to bigger things down the road.

This biography of Schuller is a complement to an earlier book written by Mulder and Martí that focuses on the Crystal Cathedral itself. That book, which I’ve not yet read, is titled The Glass Church: Robert H. Schuller, the Crystal Cathedral, and the Strain of Megachurch Ministry. What the authors do in this book is expand on what they earlier wrote about Schuller’s enterprise by diving deeper into the larger story of Schuller’s life and ministries, including the people and events that influenced his development. These influences included his family, his religious upbringing, and people like Norman Vincent Peale, who was also a Reformed Church of America minister.

The story begins in Chapter 1, where Mulder and Martí share a story from Schuller’s early life that would influence the way he viewed the world and himself. That story involves a tornado that hit his family’s farm while he was away in college. This is a story of resilience and determination that Schuller would draw upon throughout his life. So, even as his father rebuilt the house the tornado destroyed, with his own hands and the help of his family, Schuller committed himself to “fortifying the modern church.” Thus, “rather than witnessing the church utterly destroyed amid unforeseen developments within an exhausting accelerating pace of social change, Schuller initiated a decades-long project of assessing new ecclesial structures toward reassembling his cherished spiritual home” (p. 3). It is his origin story as a farm boy raised in a Dutch Reformed community (and church) in rural Iowa that plays a significant role in his vision for the church. As we see in the course of the book, Schuller sought to find ways of adapting to a world very different from that rural Dutch Reformed community of his youth. Part of that adaptation involved embracing business and market logic. It also contributed to his engagement with the Church Growth Movement led by C. Peter Wagner, then a professor of Church Growth at Fuller Theological Seminary (my seminary), but before he created the New Apostolic Reformation (that’s a different story from this one).

In the course of the chapters that follow, we encounter Schuller’s restlessness and drive to make something of himself. While he was the purveyor of possibility thinking, a theology that he developed as he sought to speak to a largely unchurched suburban southern California context that had little interest in the kind of Reformed theology he had been raised with and then imbibed at Hope College and Western Theological Seminary. As Richard Mouw notes in his foreword to the biography, it is a theology that Schuller was very conversant in and loved to discuss. It just didn’t fit his vision for growing the church. So, we learn that after seminary, Schuller was called to a congregation in Chicago, which started small but which he was able to grow to four hundred members. While he was already a successful pastor, he was restless and wanted more. Thus, as the story continues, we follow Schuller, his wife Arvella (who plays a significant role in this story), and his family to Orange County, California, where he accepted a call to plant a church in the city of Garden Grove. He accepted this call just as Walt Disney was opening Disneyland a few miles away. Because he found it difficult to purchase land on which to build a church, he decided to rent a local drive-in theater on Sunday mornings. A car-happy Southern California populace was attracted to this new kind of church. However, even in Southern California, the weather isn’t always perfect, so the uncertainty of the weather led him to purchase property on which to build. Nevertheless, the drive-in idea stayed with him, as seen with his first large-scale building, which was designed so people could worship from their cars.

One thing that is ever present in this story is Schuller’s commitment to growth through innovation and implementation of business practices. While he had a strong education in theology, he discovered/decided that sermons rooted in the bible would not reach the middle-class residents of Orange County. Therefore, he turned to psychology as a guide and developed a therapeutic message, much like his mentor Norman Vincent Peale, to attract an audience. Attract them he did. We also see how he believed that buildings would play a role in this effort, such that he was willing to push the limits financially and architecturally to achieve his goals. If one knows Schuller and his ministry, one will recognize many of the elements of his initial success. But there is more to Schuller’s story.

We see in the biography the ever-present drive for success that took hold of him early in life. However, we also learn about an underlying insecurity that drove him in his search for success. While he offered a message of possibility thinking, he lived with a strong fear of failure. This fear of failure helped drive his restlessness, a fear that would eventually undermine his ministry, such that by the time he tried to pass it off to his successors (family), it was bankrupt. There is a sense of sadness about this story that will surprise many. We discover that a major reason why the ministry went bankrupt, and the property was sold to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange County, was a product of his refusal to recognize the limits of his power to control his destiny and that of his ministry. That inability to recognize these limits was due in part to his origin story as an Iowa farm boy. He and Arvella (especially Arvella) viewed their ministry through the lens of the family farm, such that even as the farm was supposed to be passed on to one’s children, they tried to do the same with the church. It proved to be disastrous. Not only did it undermine the work of the church he had built, but it led to dissension within the family.

I will leave much of the story to the reader. It is worth reading, whatever your view of Schuller and his ministry. Mulder and Martí have an excellent job in telling Schuller’s story and its implications for the way we view the church. As I read this biography of Schuller, Andrew Root’s books kept coming to mind. In many ways, Schuller’s rise and fall fits into the paradigms that Root has been laying out in his books on Ministry in a Secular Age, including his most recent book about Evangelism in an Age of Despair. Root has pointed out that there are limits to the church’s ability to innovate so it can keep up with the ever-changing social context. Schuller tried to do this and, for a time, succeeded, but in the end he failed. Because Mulder and Martí are sociologists, they have a good handle on these realities. They draw on the plethora of public information available, including Schuller’s books, earlier biographies, newspaper and magazine articles, both church-related and secular, as well as numerous interviews with colleagues, church members, and others, including his son Robert A. Schuller, who was supposed to be his father’s successor. However, Robert A. Schuller ended up resigning because he faced opposition from his family to his vision for the church, a vision that might have saved it from financial ruin.

Gerardo Martí and Mark Mulder have written a biography that reveals a full picture of Schuller’s life and ministry. The picture isn’t always pretty, but while they reveal the complicated nature of Schuller’s personality and life, they do so critically but also sympathetically. To say they write sympathetically is not to say they agreed with Schuller’s theology or his vision, nor do they refrain from portraying a man driven by ambition as well as a fear of failure. But they recognize he was a complicated human being, he was the product of his upbringing and his context, and perhaps even a bit of Calvinist theology. Ultimately, I believe that The Church Must Grow or Perish: Robert H. Schuller and the Business of American Christianity will speak to many clergy who have been pressured to achieve greatness. Schuller’s story reminds us that there are costs to pursuing such a course for the individual pastor and the church.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books, including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.