As a young adult, he became a devotee of a rising authoritarian. So zealous and well-backed by wealthy sponsors, the young man quit college to organize youth for the new politics. He was effective. He spoke compellingly and won over thousands of thousands to his conservative nationalist movement with a religious facade. With his self-confident charisma, articulateness, photogenic machismo, and organizational success, he became he favorite son, virtually a member of the family, to the nation’s leader. He rose quickly to national prominence, garnering massive ideological and financial support. Indeed, he was a human turning point for the machinations of his master, a prophet to the next generation, herald of nationalist religion, and recruiter of naïve sheep to the new fold.

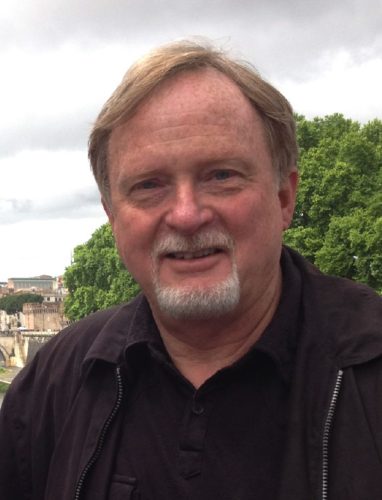

Duane Larson

I refer not to Charlie Kirk, but to Baldur von Schirach. Schirach was the “Jugendreichsführer,” the head of the Hitler Youth. Soon after Charlie Kirk’s death, many persons of the print and digital commentariat compared Kirk’s Turning Point, USA work to that of Hitler and other authoritarians. Some less reactive and more thoughtful analyses rightly called that comparison wrong. Instead, they correctly named Schirach as the more apt analog.

But those comparers did not do much more than assert. I presume readers know enough about Kirk so that I need not detail him here, while an outline about Schirach would be helpful. Similarities do abound. Schirach became a passionate devotee of Hitler at the age of 17 in 1928, so committed that he left his university studies to become a pioneering organizer for Hitler. Then there is, of course, his racism. He exuded Aryanism in his physique as well as speech. Schirach was overt in his White male superiority. He was so convinced that he must so correctly exemplify patriarchy that he followed Hitler’s insistence on whom to marry. And he opportunistically preyed on the religious and social naiveté of his youth audience to lure them into the stiff embrace of fascist White, male-dominated religious nationalism. In all these but for the arranged marriage, Kirk acted comparably.

Schirach and Kirk were also similar in their being their own persons. The Christian command to interpret others as charitably as possible leads to my observation that each apparently had their limits as to how much they should agree with and follow their fascist leaders. If one were to assume good faith on Schirach’s part, in his Nuremberg war crime trial he confessed he had believed he “was serving a leader who would make our people and the youth of our country great and happy and free,” a leader who was “unimpeachable,” until Hitler had begun mass murder. Still, “the guilt is mine,” Schirach confessed. “This is my own–my own personal guilt. I was responsible for the youth of the country. I was placed in authority over the young people, and the guilt is mine alone.” As for Schirach’s role after he was transferred from serving as chief of the Hitler Youth to Vienna as its Gauleiter, supervising the rounding up and deportation of Vienna’s Jews, he claimed the innocence of ignorance about their ultimate fate, thinking they were to be sent only to “processing centers.”

We cannot say that Kirk so repented of his belief in Trump as the one who would indeed make America great and its people happy. With the objective tragedy of his murder, we can only say that he was not given the opportunity of years of seasoned self-understanding to engage publicly in self-reflection. We do know that he was clearer about his personal moral stance on abortion than is Trump. We know too that Kirk was more principled about immorality like rape and pedophilia; he was clear in his demand that the Epstein files be released to the public. We also know that Trump perceived Kirk as less hateful than Trump himself. At least so Trump confessed at Kirk’s memorial service. However, a dispassionate analysis of Kirk’s racial and gender humor may conclude that Kirk’s hate simply was masked with a better smirk and more finessed rhetorical charm. Kirk’s rhetoric, of course, was more effective than his knowledge of the facts. This worked for him when with anxious and naïve college students in so-called “debates,” not so much when his sophomoric ignorance masked by a practiced cleverness was outed for what it was in venues like Cambridge. Finally, we can agree that however he distorted the essentials of Christianity (as obviously also did Schirach), Kirk considered himself to be a Christian and knew his own basic Christian fundaments, unlike Trump. Schirach clearly differed here. Though raised Catholic, he rejected Christian terms and reframed faith in the messianic mythology of nationalist blood and land, quite like Hitler.

Yet, as correct as these summary comparisons might be of the proto-Christian Nationalist Schirach and full-blown Christian Nationalist Kirk, the greater similarity is in the times and generations they represent. They are similar because the political and spiritual situations on which they capitalized are similar. This matter calls for a theological analysis if we are to recognize and, we pray, avoid the ultimate spiritual disaster they re-presented.

Freedom–Church–Truth

Tim Snyder’s work on tyranny and freedom now enjoys an indispensable “go to” status in our contemporary American scene. Snyder pays attention to the prepositions, especially when thinking about freedom. He notes that the de facto understanding of freedom is “freedom from,” as in freedom from a king, freedom from oppression, freedom from anybody else’s will. Hitler promised his people freedom from financial ruin and low self-esteem, and they got it. He turned the post-Weimar economy around and joblessness plummeted. How he did so was far more awful even than ICE officers violently rendering citizens invisible, but his people were happy again. Americans today of every age want freedom from economic constraint, which would mean a turnaround from a fading American dream. Both political parties play to that desire with competing visions. The recent off-year elections show, “affordability” still motivates more than the evident moral capital of the candidates.

“Freedom from” by itself begets problems. If it is the only or even primary understanding, freedom bears no obligations. It is self-orienting, individualistic, and so inevitably invites manipulation of people by people toward selfish ends. Snyder notes the obvious requirement of freedom requiring a “to” beyond the self; freedom at the least to ensure the freedom of others by rule-setting and systemized protection and defense of all selves. In effect, Snyder translates into secularized and relative terms Martin Luther’s truth-recognition that a Christian is both perfectly free and perfectly duty-bound to the neighbor. Luther speaks in ultimate terms that necessarily define a Christian’s essential moral posture. Snyder and Luther both agree that freedom includes a purpose; it is not a prelude to anarchies. Luther and most religious traditions, however, affirm always that freedom intends the good of the neighbor.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer saw in Luther’s definition of the Christian as free and servant an essential element of the Church. A person insufficiently practices servanthood “to” if that servant in freedom is not “with” the neighbor, “with” the Other. There’s a whole lot of Hegelian dialectic going on here with Bonhoeffer; that I am not sufficiently “I” without the otherness of the Other and vice-versa; that I cannot be me no matter how I “gotta be me” in some Sinatra-esque self-delusion without you, dear reader, along with every other very different persons in whom Christ himself also has taken residence. These are those for whom we necessarily serve to and with if we are to be persons, nay more, Christians, at all. A person is only so and always growing so insofar as a person is in freedom with others in their particularity and in their concreteness.

German Chancellor and Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler arrives at the stadium during the Party Congress (Reichsparteitag der NSDAP) held in Nuremberg in September 1934, for a meeting with members of the Hitler Youth (German: Hitlerjugend, HJ), the youth organization of the German Nazi Party (NSDAP). Walking beside him is the leader of the Hitler Youth, Baldur von Schirach.

And this is also in larger size and deepest quality what it means to be Church. In contemporary terms, a person is only so and the Church (!) is only so, as it were, with its embrace of DEI. The Church speaks from, for, and with God and humanity. In so far as we belong to the Truth, notwithstanding the conditions of our situations and contexts, everyone who belongs to the Truth listens to Christ (John 18:27). For Bonhoeffer, and Christianity, the Church which is to be salt and light and healer of the world is in the world and thereby changing the world with the same relational dynamism of “to-ness” and “with-ness” as the Church has in itself. It couldn’t be any clearer that any Schirach or Kirk or other declaimer of empathy is in the deepest spiritual danger when their “freedom” is so bereft not only of “to,” but of “with.” We church-types typically speak of mission trips “to” such and such. We do better when we speak and care “for” or “of” others. But those prepositions, along with “to,” still tempt us into treating the other as a cipher, a statistic. Freedom “with” requires a concrete, even very familiar, knowledge of the neighbor.

“With” then requires us to speak truthfully and truly as best as we can given our contexts of and for our neighbors. Calling a politician a “communist lunatic” or a black airline pilot “inherently deficient” or a woman “weaker” and so on are readily used slurs by fascist-adjacents. Obviously, they are not truth-telling. They lie. They bear false witness. We may respond by saying such things are “just politics.” But normalizing such “free” speech in our politics simultaneously shatters the whole of the Decalogue, which, ironically, so many who oppose the DEI principle of being Christian would also plaster on a wall of every classroom.

They forget, if they ever knew, that there is no sequencing of higher to lower in the two tables. Every commandment intimately relates to every other. Break one, you basically have broken them all. For God, intent and act are co-equal. Jesus himself had something to say about that. Sexual infidelity denigrates the humanity of all persons involved. Stealing a person’s income by robbery or unjust tax policy deprives them of a happy future. In so trivializing and objectifying them you may as well have deprived them of life itself. That is not being with them in their concrete bearing of God’s image. So also you will have shredded the first commandment itself. If freedom is only “from” and there is no “with,” for such an ideologue there is no God. There is no such thing as “just politics” except for those who have fallen to the illusion that they are their own sovereigns, pure and simple.

Much more could be said and in much more detail. The most important takeaway is that the similarities represent much more than those of two individuals. These markers characterize the belief systems of Schirach and Kirk because they also were more pronounced markers of the times and audiences. They were seeds already sprouting which Schirach and Kirk nurtured and cultivated. To be sure, misunderstandings of freedom-church-truth have ebbed and flowed over the centuries, just as fascism and other tyrannies have never been fully quelled, just as there was no end to history even after the falls of the Berlin Wall and of the Soviet empire.

And just as Bonhoeffer urged his colleagues who gave their obedience to the German Church that they should know better, so should we. Our generations from Boomers to Gen Z are on the same trajectory, as was Kirk with Schirach. Schirach himself instructed that these words mark his gravestone. “Ich war Einer von Euch.” “I was one of you.” ‘Euch’ is in the familiar second person plural. Schirach knew his people well. As efforts continue to memorialize Kirk in stone and story, would Schirach’s epitaph be fitting for Kirk, too? For us? How can we do better at correcting not just youthful naiveté, but willful ignorance across generations that abets emergent fascism yet again?

Duane Larson (MDiv, PhD) is a systematic theologian and pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). He taught at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg (now United Lutheran Seminary) and served as President of Wartburg Theological Seminary before concluding his full-time ministry career as Senior Pastor of Christ the King Lutheran Church in Houston (where he also taught at the University of Houston). He is the author/editor of over 50 articles and several books, including “Ubi Deus Dixit: Where God Has Spoken — The Lutheran Doctrine of Two Kingdoms.” He now resides in Princeton, IA.