The reaction never varies when someone realizes Alan Sherouse is the son of well-known Baptist preacher Craig Sherouse.

Alan Sherouse

|

“They always say, ‘Oh, you’re Craig’s son,’” said Sherouse, pastor of Metro Baptist Church in Manhattan. “I call it ‘getting sonned.’”

And it’s just one of the many gifts Sherouse said he’s gotten from his dad, the senior pastor at Second Baptist Church in Richmond, Va. That’s because his father is his mentor.

“My father has been the greatest influence on me as a minister.”

Sherouse and others who have followed their dads into ministry say the experience is like a Father’s Day gift in reverse. Unlike other seminary-trained ministers, they can draw on a lifetime of learning how to prepare sermons, visit the sick and handle church conflicts.

But their dads say the gift has also been theirs. Witnessing their sons develop into spiritual leaders deepens their own ministries in ways they never knew possible.

“One of the most touching part of this is to be asked by your son for advice about this life we share,” Craig Sherouse said.

Scholar: ‘Like an apprenticeship’

Second- and third-generation ministers aren’t the norm for several reasons, said Bill Leonard, former dean at the School of Divinity, Wake Forest University. He now teaches Baptist studies and church history there.

He was involved in the education of both Sherouses and of several other parent-offspring seminarians.

Children often reject any notion of ministry to avoid being compared to the parent pastor. In other cases, feelings of pressure to become ordained can even obscure the sense of calling, Leonard said.

Others “have seen the struggles their dads have had in congregations and decided ‘this is just something I am not going to get into,’” he said.

But then there are those who do follow. Often in their cases the calling is nurtured by growing up a preacher’s kid, Leonard said. That’s when childhood serves as a training ground.

“That’s almost like a little apprenticeship, whether it was intentional or unintentional.”

Applied no pressure

Bill Wilson

|

It was definitely unintentional for Bill Wilson, president of the Center for Congregational Health in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Wilson, whose son, Ryan, graduated from McAfee School of Theology in May, is also the son of a pastor. He felt no pressure to become a minister because “dad was very careful not to put that burden on me.”

Wilson said he worked equally hard not to influence his son’s decision to enter the ministry. Ryan, by then a college graduate, was serving in an HIV/AIDS ministry in South Africa in 2008 when he felt the tug.

“I’m glad he made that decision 8,000 miles from us,” Wilson said.

“There’s nothing worse than going into the ministry to meet someone’s expectations,” Wilson said. “If it’s not a call, please say no, because that will wear off in about three weeks.”

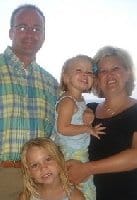

Bill and Ryan Wilson embrace at Ryan's ordination service in May.

|

‘No way, definitely not’

The absence of parental pressure is one of the gifts Ryan Wilson said he got from his father.

But sometimes others weren’t so careful, and he was often asked if he intended “to become a pastor like your dad,” he recalled.

“No way, definitely not,” was always the answer, he said.

“I was almost against being a minister because my dad was a pastor and my grandfather was a pastor, and as a young kid I wanted to do my own thing,” Wilson said. “I didn’t want to do what people expected.”

In August he’ll begin an internship at Metro Baptist where part of his duties will include social outreach.

It was precisely not trying to influence him that his dad and late grandfather “helped me become the minister I am now.”

Seeing it lived out

The intangibles to successful ministry are the gifts Florida minister Chris Cadenhead said he got from his dad, Al Cadenhead.

Al Cadenhead

|

One of them was how to balance family and church life and how to set boundaries with people in the congregation, said Cadenhead, senior pastor of Bayshore Baptist Church in Tampa.

“One of the balances in ministry is being accessible and engaged with your people … and yet holding onto a sense of identity,” Cadenhead said. Al Cadenhead, the senior pastor at Providence Baptist Church in Charlotte, N.C., also demonstrated how not to become consumed by the job. “I saw it being lived out,” Chris Cadenhead said. ‘It’s scary’ Having his son follow him into ministry was a blessing because it confirmed Chris didn’t have a negative church life growing up,

Al Cadenhead said. Preachers’ kids often leave God and church behind as adults as a result of experiencing toxic congregations, he said.

Another gift is seeing his son preach. “I watch him and it’s scary how much of me I see in him,” Cadenhead said. “He and I do reflect each other pretty strongly.”

Chris Cadenhead and family

|

‘My favorite preacher’

The sermon part also is a blessing for Craig Sherouse.

His son is well prepared, always has something significant to say, is good with the text and is a masterful storyteller, he said. “He is my favorite preacher.”

Something he never predicted was how stirring it is to have a son share his vocation.

“One of the most heart touching parts of this is to be asked by your son for advice on this life we share,” he said.

Alan confirmed that, but said he really comes out ahead because he’s also able to tap into his father’s vast network of church friends and pastors.

He said his dad also taught him, through example, not to bring church problems to the dinner table.

“That was a great gift and who knows where I’d be without it,” Alan Sherouse said.