(The Conversation) — Handwashing has gotten substantial coverage this past year during the COVID-19 pandemic, and not just for hygiene. You may have encountered some of the many accusations in both the U.S. and Canada that a politician has “washed his hands” of pandemic responsibilities. Sometimes the reference includes a nod to the historical figure associated with this phrase: Recently in the U.S., a conservative commentator faulted President Joe Biden, saying he is “like Pontius Pilate: just washes his hands and stays quiet.”

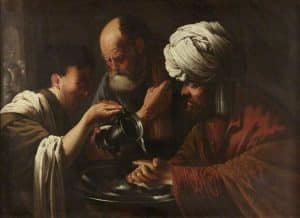

‘Pilate Washing his Hands,’ by Hendrick ter Brugghen, 17th century. (Shipley Art Gallery; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation/Wikimedia Commons),

These handwashing images derive from iconic biblical scripture referring to events preceding Jesus’s crucifixion. In one of the earliest versions of these events, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea from at least 26 to 37 CE — the only man with the power to order a crucifixion — washes his hands before a crowd. In the Gospel of Matthew, he simultaneously assents to Jesus’s execution and claims no personal responsibility.

Throughout the history of Christianity, representations of Pilate’s handwashing have often been used to shift blame for Jesus’s death to Jews, and have been part of a toxic legacy of Christian and western antisemitism.

The Historical Pilate

In the first century CE, the Roman empire ruled the sub-province of Judea through military governors like Pilate, who were tasked with quashing any rebellions against Roman rule. Pilate was the only person in Judea with the authority to execute someone by crucifixion, a brutal form of capital punishment reserved for slaves and non-citizens deemed subversive.

Helen Bond, professor of Christian origins explains that “the execution of Jesus was in all probability a routine crucifixion of a messianic agitator” by a Roman governor. Jewish sources convey that Pilate was hostile toward Jews and their customs. Philo of Alexandria even lamented Pilate’s “continual murders of people untried and uncondemned.”

Yet, the New Testament gospels offer ambivalent portraits of the man who ordered Christ’s execution. There are four different accounts of Jesus’s sentencing and death, but all agree Pilate was reluctant to declare Jesus guilty.

Each gospel depicts Pilate finding Jesus blameless but acquiescing to execute him, whether due to personal weakness, to appease the crowds or to legitimate his own authority and the emperor’s. Instead of impugning Pilate, the gospels shift the blame for Jesus’s death to Jewish authorities.

Each of these gospels was written during the decades following the destruction of the Jerusalem temple by the Romans (70 CE), the climax of the First Jewish Revolt. This was a period of rampant anti-Judaism: imperialist media such as coins and monuments indiscriminately linked Jews from across the empire to the rebels in Judea and cast Jews as barbaric traitors. The empire punished all Jews, for instance, with a tax.

This created a challenge for those early followers of Jesus — both Jews and gentiles — who proclaimed that their Savior was a Jew whom Rome executed as a criminal. The gospel authors stressed that Jesus opposed the Jewish authorities and was not found guilty by the Roman governor.

Transferring Guilt

How to understand depictions of “Jews” in gospels written before the self-identification “Christian” became widespread in the early second century is thus immensely complicated. The Gospel of John, for instance, emerged from a gentile community. It never uses the term “Christian” yet distinguishes followers of Christ from Jews through hostile rhetoric demonizing “the Jews” as children of the devil, as the New Testament scholar Adele Reinhartz has shown.

Matthew’s gospel, however, was produced by a community of Christ-followers who more clearly fit within the spectrum of Jewish identities, yet were eager to distinguish themselves from Jewish leaders who had been involved in the revolt and post-war Jewish leaders (namely, the rabbis). In this case, rhetorical attacks against certain Jewish leaders reflect an inter-sectarian argument among Jews.

The pattern of exonerating Pilate by blaming Jewish leaders is unmistakable in Matthew’s gospel. It includes a “blood curse” that is the basis of a toxic formula that Christians have used to justify centuries of Christian anti-Judaism, often resulting in reprehensible acts of violence against Jews: “So when Pilate saw that he could do nothing … he took some water and washed his hands … saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.’ Then the people as a whole answered, ‘His blood be on us and on our children!’”

Matthew also writes “the chief priests and the elders” were manipulating the crowds. He often accuses Jewish leaders of such corruption as well as hypocrisy and misunderstanding the Jewish law.

Pilate’s handwashing alludes to an older account from Jewish scripture. Deuteronomy 21:1-9 prescribes a ritual through which Israel can be “absolved of bloodguilt” for a murder committed by an unknown person. Because the culprit can’t be prosecuted, this ritual removes “bloodguilt,” or communal liability for “innocent blood,” that would otherwise remain in the midst of the people of Israel.

The rite entails the people’s elders washing their hands of bloodguilt while priests break a heifer’s neck. Matthew inverts Deuteronomy’s ritual, and casts the priests and elders as hypocrites who invited bloodguilt onto their kinfolk.

Through early Christian writers, Pilate became an even more positive figure by the time the Roman Empire adopted Christianity. Some considered Pilate a Christian, at least “in his conscience,” as the early theologian Tertullian wrote. The Coptic Church proclaimed him a saint in the sixth century. Pilate even appears in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan creed, a Christian statement of faith: Jesus was “crucified for us under Pontius Pilate.” Note the statement says “under” and not “by” Pilate.

Ancient Christian texts doubled down on the New Testament gospels’ shifting of blame from Pilate to Jews, as professor of the New Testament Warren Carter has shown. Christian authors deployed ambivalent and positive images of Pilate to show that Christianity was not a threat to Roman law and order.

In doing so, they fanned the flames of anti-Judaism. Art historian Colum Hourihane has explored how these anti-Jewish interpretations eventually led to negative characterizations of Pilate himself as a Jew during the medieval period in Europe. At this time, Christians blamed Jews for plagues.

Politics of Handwashing

Some accusations of handwashing rightly seek to hold political leaders accountable, or point to the tightrope politicians walk to meet political objectives. Pope Francis declared that those who ignore suffering caused by COVID-19 are “devotees of Pontius Pilate who simply wash their hands of it.”

But the expression should also remind us of the dangers of vilification: As we saw under former president Donald Trump’s pandemic leadership, when leaders or communities distinguish themselves through scapegoating, this facilitates a dangerous redistribution of guilt to other parties, often marginalized and racialized communities.

Like Trump, political influencers have vilified people of Asian descent, and both the U.S. and Canada have seen a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. Some conspiracy theorists have falsely blamed Jews and Israel for the virus. Some politicians and commentators have divided communities directly or indirectly through blaming or singling out people living in poverty, Blacks, or Indigenous communities.

The history of interpretations of Pilate’s handwashing is stained by malicious attempts to define Christian identity through the demonization of Jewish others. Whether seeking to explain problems, to hold people accountable or to assert our own identities, let’s do so in ways that don’t dehumanize anyone.![]()

Tony Keddie is an assistant professor of early Christian history and literature at the University of British Columbia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.