(RNS) — A friend recently returned from visiting his elderly parents, both of whom, in their 80s and 90s and living in Texas, have refused a COVID-19 vaccination. The few other members of his extended family gave in to pressure and got one, but only after another of them had died. Meanwhile, hundreds of Texans were going about their daily lives unmasked — visiting bars, restaurants, and movie theaters — while the delta variant raged, producing stunning casualties among the vulnerable.

When he came back, my friend asked me, “Are the vaccine resistant and deniers my enemies?”

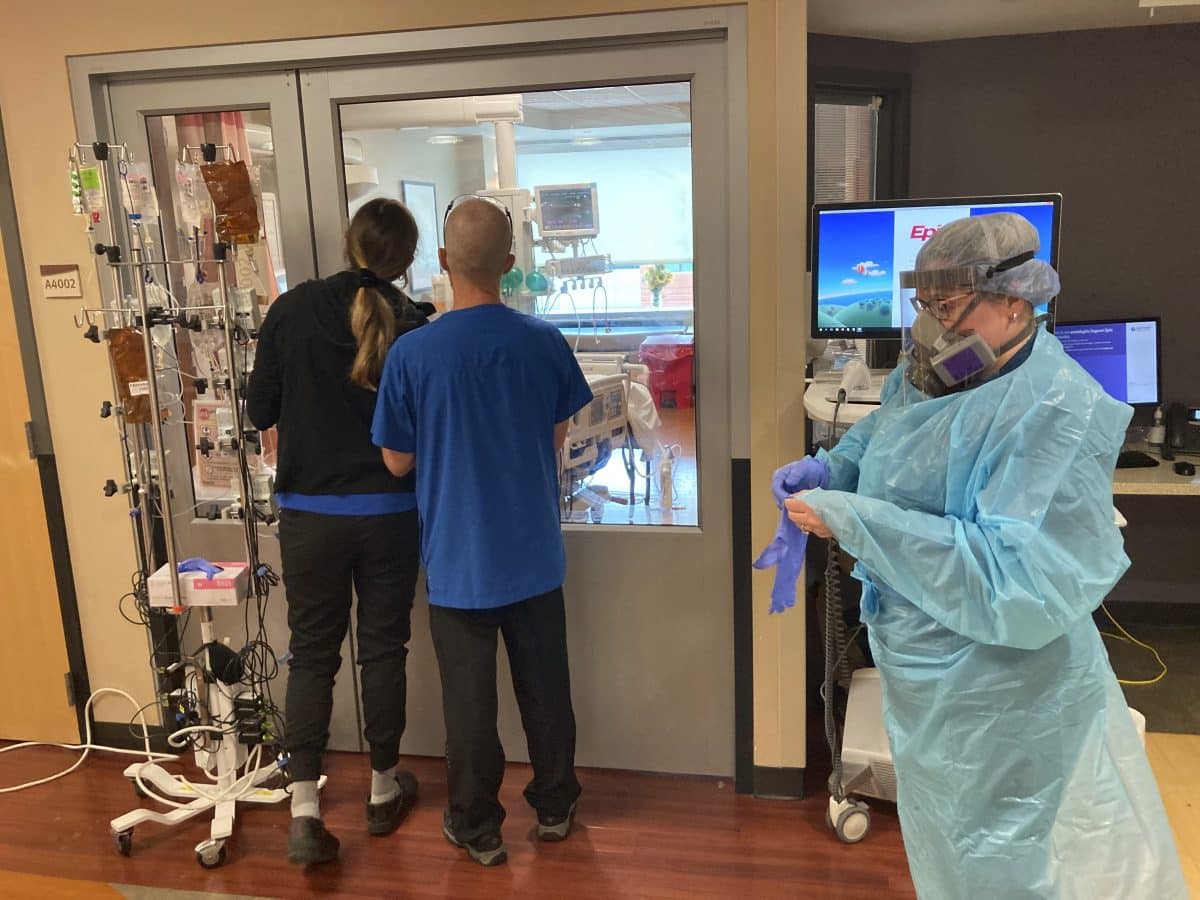

Two visitors peer into the room of a COVID-19 patient in the intensive care unit at Salem Hospital in Salem, Oregon, on Aug. 20, 2021, as a nurse dons full protective gear before going into the room of another patient. (Andrew Selsky/Associated Press)

I saw immediately this friend, a theologian whose work involves preparing people for lives of compassionate service in the church and the world, was experiencing the compassion fatigue I see in other people in my life. Empathy for the vaccine hesitant is giving way to frustration and anger.

As the country tips into another trough of high transmission, full ICUs, and hybrid classes, it’s difficult to muster up sorrow for people who sneeringly call masks “muzzles” only to infect and sometimes kill loved ones and strangers. Lately we’ve been asked to root for people who refused the vaccine because it’s “experimental,” but now explain that their close call with death was avoided only by an experimental, and costly, treatment at the hospital.

Those who took the pandemic seriously, and made life-altering decisions all along to protect others, are being asked to dig deeper into the well of compassion to ladle out another cup or two of sympathy. But for many that well is dry. At the 18-month mark in the pandemic, our emotional resources are tapped, or are reserved for the children we are sending to school or elderly parents we dread we will lose because of the carelessness of others.

In the church we’re often taught that empathy is a silver bullet that puts an end to our conflicts, anxieties and differences. If we understood one another, the story goes — if we could put ourselves in the shoes of another person, as the New Testament teaches — we would see that our problems boil down to misunderstandings.

The shine on this promise has worn off, and I am relieved for it. Our differences with those who willfully dismiss COVID-19’s dangers are not fiction. When their carelessness causes harm it’s not surprising that compassion wears thin. Empathy is only as good as the world it produces.

Does this mean that we get a free pass, and treat COVID-deniers and vaccine opponents like enemies?

There are certainly times when speaking truth to our vaccine-hesitant neighbors includes making our anger and frustration plain. We may also need to separate ourselves from people who harm, from anger that becomes poison if it stagnates.

As a Christian, I hold this alongside another truth: We can continue to urge one another toward redemption, even those who are responsible for their own destruction. We can allow our anger to coexist with hope.

In the New Testament’s Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is often at his wit’s end with the disciples’ behavior: They argue over which of them is the best. They bicker and fight. In these moments Jesus’s anger burns on the page.

For me, the most painful moment of this frustration comes in the garden of Gethsemane, as Jesus begs his disciples to stay awake with him as he prays on the night before he will be tortured to death. Instead, Jesus returns to find his closest friends asleep.

“Could you not stay awake with me one hour?,” he asks his negligent followers.

Yet in his frustration, anger and disappointment, Jesus persistently longs for and works toward the redemption of a world that will reject him. His human emotions — his exhaustion and trouble — don’t distract from this purpose. Instead, he treads the complicated terrain of being vulnerable, a person of flesh and blood. His anger does not negate his hope for redemption. Instead, his anger is a testimony to the force of that hope.

I hope my friend who is angry, disappointed, and frustrated at family members who refuse to vaccinate will unyoke his anger from his hope in redemption.

More immediately, my anger can coexist with a longing for freedom for those who believe in conspiracy theories. I know their liberation is tied to mine. I can advocate for myself and my community without ceding to retribution or revenge on those who cause harm.

That’s the power and promise of empathy. When those wells of compassion run dry, we can continue to follow after Jesus, whose anger and frustration coexisted alongside the gift of grace, even for those who could not yet receive it.

Melissa Florer-Bixler is pastor of Raleigh Mennonite Church and the author of How to Have an Enemy: Righteous Anger and the Work of Peace.