WASHINGTON (RNS) — Members of the Congressional Freethought Caucus met with a group of scholars and activists on Thursday evening (March 17) to review a new report detailing the role Christian Nationalism played in the insurrection that took place at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. The meeting was a rare instance of lawmakers openly addressing the prominence of religious expression during the attack, which was evident on Jan. 6 but has not been a central focus of public discussions on Capitol Hill.

California Democratic Rep. Jared Huffman, who said he first discussed the role of Christian Nationalism and the insurrection with some of the panelists last summer, hosted the meeting for a slate of lawmakers that included Maryland Rep. Jamie Raskin, a co-founder of the Freethought Caucus who also serves on the House Select Committee investigating the attack.

Raskin opened the virtual briefing by noting that while a variety of ideologies were represented among insurrectionists, Christian Nationalism “clearly figured highly in the events of the day,” and was “a unifying theme for many of the factions that assembled on January 6.”

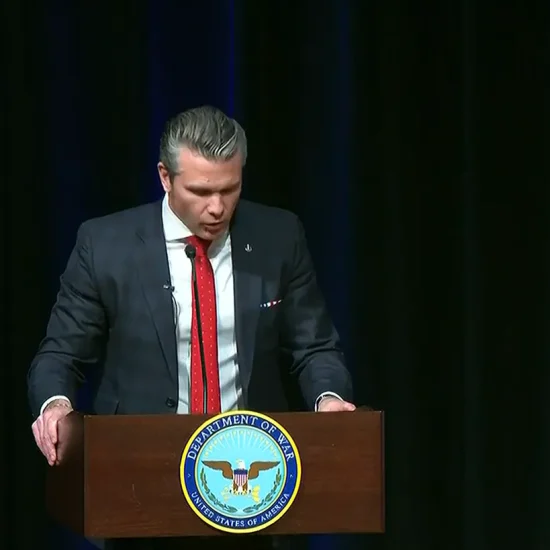

Supporters of President Donald Trump overtake the inauguration stage in front of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington, D.C. (Jose Luis Magana/Associated Press)

His words were echoed by an array of panelists who presented findings from a recent report they helped author with backing from the Freedom from Religion Foundation and the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. Among other things, the 66-page study documents in painstaking detail the prevalence of Christian Nationalist symbols and rhetoric at the insurrection and a series of events that led up to the storming of the Capitol.

Amanda Tyler, head of the BJC, told lawmakers the report faced “defensive pushback” from some conservative Christians after it was unveiled last month but has been embraced by Christians who see opposing Christian Nationalism as a religious call.

“Let’s be clear: Christianity does not and cannot unite Americans under a national identity,” Tyler said, adding that Christian Nationalism “debases Christianity.”

Samuel Perry, a University of Oklahoma sociologist and co-author of Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, told lawmakers he and others who study the ideology often use the more specific term “White Christian Nationalism,” because data indicates Christian Nationalist sentiments appear to “perform differently when white Americans affirm them as opposed to non-White Americans.”

He was followed by Jemar Tisby, a historian and head of Black Christian collective The Witness, who contrasted White Christian Nationalism with fusions of faith and activism among Black Christians.

“In contrast to White Christian Nationalism, Black Christians have historically tended to embrace a kind of patriotism that leads to an expansion of democratic processes, the inclusion of marginalized people and a call for the nation to live up to its foundational ideas,” he said.

Andrew L. Seidel of the Freedom from Religion Foundation, a chief author of the report, closed out the briefing presentations by outlining the way Christian Nationalism operated as a “permission structure” for activists, arguing it gave them “the moral and mental license they needed” to participate in events such as the Million MAGA March and the Jericho Marches in the months prior to the insurrection, as well as to attack the Capitol.

“(There were) other motivations and drivers of this attack, but this Christian Nationalist permission structure — doing God’s will, fighting for God’s law, returning the country to its Christian roots — pervaded a lot of those other obvious drivers of this attack.”

Lawmakers appeared largely convinced by the report, peppering the panelists with questions over the course of the hour-long briefing.

“I think the proof points about just how central Christian Nationalism — we should call it White Christian Nationalism — was to the planning and the execution of the insurrection is really undeniable,” Huffman told Religion News Service in an interview.

Asked by Rep. Jerry McNerney, a California Democrat, to define the “fundamental core” that unites Christian Nationalists (“I don’t think it’s belief in Jesus,” McNerney quipped), Perry argued it was an “ethno-culture.”

“This blends the idea of kind of an ethnic identity — this is the white part of it, but also ethnic implies a part of culture,” Perry said. “Religion is a part of this, but also an understanding of White — not necessarily White race, but whiteness. This combination of perceptions (that) the nation rightfully belongs to ‘people like us’ — and by people like us I mean, the ethno-culture, the white Christian conservative, traditionalist, almost certainly native born.”

Multiple lawmakers, such as Rep. Mark Pocan of Wisconsin, expressed concern about the role of Christian Nationalism in ongoing fights with school boards across the country. School board meetings have become a staging ground for heated disputes over COVID-19 restrictions and supposed use of critical race theory, featuring many activists who have invoked religion. Several candidates currently running for school board seats across the country, Pocan said, appear to be tied to Christian Nationalism.

Raskin also mentioned Christian Nationalism’s pervasive role in ongoing political disputes.

“More than a year later, Christian Nationalists continue to join forces to try to challenge our democratic institutions and values — whether it’s in the suppression of voting rights or the promotion of various culture, more battles, including to my mind the utterly fraudulent attack on critical race theory,” he said.

Seidel agreed, noting he planned to send testimony to the Jan. 6 selection committee on the subject. He argued that while there was a “moment of shame” among Christian Nationalists immediately following the insurrection, many have since “adopted the insurrection and seem emboldened by it.”

He pointed to data showcased by Perry during his presentation that showed shifting views of the insurrection among Christian Nationalists over the past year. In February 2021, immediately after the insurrection, 75% of white Americans who scored highest on Perry’s Christian nationalism index — a series of questions that gauge Christian Nationalism — said those who attacked the Capitol should be caught and prosecuted. By August of that same year, the number dropped to only 54%.

By contrast, those who scored the lowest on the Christian Nationalism index barely budged in that same timeframe, with around 95% saying both times they were asked that the insurrectionists should be caught and put on trial. Similarly, slightly less than 15% of hardline Christian Nationalists in February 2021 agreed with the statement “I stand with the protesters who stormed the Capitol.” Come August, that number went up to 26%.

Raskin also asked whether panelists believed Christian Nationalism played any role in inspiring what he described as “the medieval violence” of Jan. 6.

Seidel responded by arguing that prominent Christian nationalists used “very militant” language in the lead up to Jan. 6, often couched in the rhetoric of “spiritual warfare.”

Among the incidents chronicled in the report is a speech by Stewart Rhodes, the leader of the militant group Oath Keepers, who is currently facing sedition charges for his alleged role in the insurrection. Delivered at a faith-themed “Jericho March” event in Washington, D.C., on December 12, 2020, Rhodes threatened a “bloody war” if the 2020 election results weren’t overturned.

When he finished, the event’s emcee, conservative Christian commentator Eric Metaxas, responded: “Oh, God bless you. This guy’s keepin’ it real, folks.”

Similarly, the night before the insurrection, Tennessee Pastor Greg Locke stood before a crowd in Washington and prayed for Enrique Tarrio, the leader of the militant group Proud Boys who now also faces charges related to the insurrection. Locke said: “We just thank God that we can lock shields, and we can come shoulder-to-shoulder with people that still stand up for this nation … God, help us to live, help us to fight, and if need be, lay down our life for this nation.”

Tisby added that historical efforts to “enforce this vision of a White Christian Nationalist America” — particularly those used to further racist goals — often didn’t have to use explicit calls to violence. He pointed to the example of onetime Mississippi senator and Ku Klux Klan member Theodore G. Bilbo, who declared in 1946 that the best time to stop Black people from voting is “the night before.”

Huffman closed out the meeting by asking panelists how best to combat Christian Nationalism. The panel advocated for an embrace of the separation of church and state, the building of a “coalition of the religious willing” to combat Christian Nationalism and the marginalization of the ideology.

Huffman echoed the panelists after the event, saying the “antidote” to Christian Nationalism is “defending the line of separation between church and state.” The Freethought Caucus, he said, will continue to stay engaged with dialogue around Christian Nationalism in the future.

In the meantime, questions remain as to how to broach the topic of Christian Nationalism among his colleagues on Capitol Hill. Asked after the event whether he saw Christian Nationalism among members of Congress ahead of the insurrection, Huffman laughed, replying: “Is that a rhetorical question? Of course.”

“We had colleagues at the ellipse for the pep rally that launched the insurrection,” he said, referring to the rally in support for former President Donald Trump that immediately preceded the Capitol attack. “If you look at their talking points, they just check every box on the White Christian Nationalist agenda.”