(RNS) — Over the past decade, Jemar Tisby’s life has largely been shaped by two forces: the Bible, and the deaths of young Black men, often at the hands of law enforcement.

About a decade ago, Tisby, then a seminary student in Jackson, Mississippi, helped start a new group called the Reformed African American Network — an offshoot of the “Young, Restless, and Reformed” movement that had spread like wildfire among evangelical Christians in the first decade of the 21st century.

The group hoped to write about racial reconciliation from the viewpoint of Reformed theology, the ideas most closely associated with the ideas of John Calvin and popularized at the time by preachers and authors such as John Piper. But amid this resurgence of Reformed thought, there were few resources to be had on race issues.

Then, in 2012 in Florida, Trayvon Martin, a Black teen, was killed by the neighborhood watch coordinator of a gated community. All of a sudden, people in the movement were listening.

At the time, Tisby said in an interview, he and others raised their hands and said they had something to offer. The mostly white leaders of the Reformed movement, he said, welcomed them. “I believed them,” he said. “I thought, we are here, they must want us here.”

Over the next few years, Tisby, a former pastor turned history professor, became a leading voice on race among evangelicals through his writing and as co-host of “Pass the Mic,” a popular podcast.

He wrote op-eds on race and faith for The Washington Post and published the bestselling “The Color of Compromise,” which details the long history of racism in American Christianity. “How to Fight Racism,” a 2021 follow-up, was named Faith and Culture Book of the Year by the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association.

But Tisby’s success has since collided with conservative concerns about “wokeness” — a byword that encapsulates liberal critiques of systemic racism, America’s racial history, and other social justice themes.

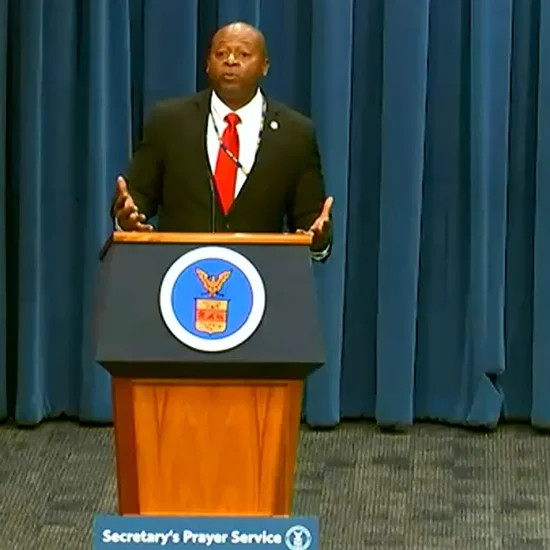

Jemar Tisby. Photo by Hawa Images

In recent months two college English professors at Christian colleges — one in Florida, the other in Indiana — have been dismissed for allegedly talking too much about race in their classes. In both cases, critics pointed to the appearance of Tisby’s work on class syllabuses to claim the professors were undermining their students’ Christian faith.

“I’ve become, for the far right, a symbol of everything that’s wrong with how people who they call the left are approaching race,” Tisby told Religion News Service.

The “woke war” playing out in school boards, on college campuses, and in church pews has been driven by activists like Christopher Rufo and by conservative evangelical authors and preachers who warn that wokeness and academic notions such as critical race theory are heresy.

As a result, evangelical pastors who were once outspoken about the need to confront racism have gone silent, or in some cases, been driven from the movement altogether.

Some black Christians — including Tisby and his colleagues at the Witness, as the former Reformed African American Network is now known, have left the evangelical world, sometimes quietly and other times loudly.

Some, like Tisby, have found it harder to leave — finding their ties to the evangelical world difficult to unwind even when they are told they are not wanted. Last year, the board of Grove City College, a Christian school in Pennsylvania, apologized for a 2020 sermon Tisby gave at a campus chapel session after an online petition accused him of promoting critical race theory.

Anthea Butler, religious studies professor at the University of Pennsylvania and author of “White Evangelical Racism,” a 2021 book about the racial divides of the evangelical movement, said evangelicals have a long history of welcoming Christians of color into their movement and then ousting them if they ask too many questions about race.

She said college leaders, like those behind the report at Grove City, or other Christian leaders who have denounced Tisby want to make an example of him as a warning to others.

“They want to punish him,” she said.

A native of Waukegan, Illinois, Tisby found Christianity while in high school when a friend invited him to a church youth group meeting. Attending the University of Notre Dame, he began to think about a call to ministry. In South Bend he also discovered Calvinist theology after a friend sent him a copy of Piper’s 1986 book “Desiring God.”

After graduating in 2002 and a year working for Notre Dame’s campus ministries, he joined Teach for America and was sent to teach sixth graders in impoverished Phillips County, Arkansas, in the Mississippi Delta.

The experience changed the direction of his life.

“This is cotton country — the land of slavery and sharecropping,” said Tisby. “You can see it in the landscape, you can see it in the generational poverty.”

The predominantly Black community was marked by a lack of jobs, poor medical care, food deserts and a struggling school system.

“The thing that struck me was that there are churches on every corner,” said Tisby. “Not only were they racially divided, it also didn’t seem like they were having much impact in the community. That’s where I started thinking about the relationship between faith and justice.”

After four years at the school, he took a year off to study at Reformed Theological Seminary in Orlando, Florida, before returning, this time as a principal.

“I just felt God wasn’t done with me in the Delta,” he said.

He finished his divinity degree at a seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, working part time in the school’s admissions office. He was charged with helping recruit Black students and helped to start an African American leadership initiative.

Afterward, he enrolled at the University of Mississippi and earned a doctorate in history. He is now a professor at Simmons College of Kentucky, a historically Black school in Louisville.

The recent pushback against his work, he said, seems both familiar and surprising. As a historian, Tisby has traced the ways American Christians have tried to claim that the faith is colorblind. The love of Jesus, they maintain, should break down divides between people of different ethnicities.

But rarely, Tisby said, do Christians manage to overcome racial differences. In “The Color of Compromise,” Tisby recounts how English settlers in Virginia faced a dilemma. In their homeland, Tisby writes, the custom was to free slaves who converted to Christianity. In 1667, the Virginia General Assembly decided that, no matter what the Christian faith taught, baptism would not make slaves free.

Tisby recounted some of that history in his 2020 chapel sermon at Grove City College. He had first been invited to speak in 2019 but his visit had been delayed by scheduling conflicts and complications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

School leaders later said they had invited him as a Christian writer who could help the school’s students grapple with racial reconciliation. Tisby, who had spent years in white evangelical spaces, felt he had a message the students there could hear. “What I picked up on was, we’re willing to give you a hearing, but this is not what we typically do,” he said.

A year later a group of alumni and parents from Grove City launched a petition, claiming the school had been overrun by “wokeness” and CRT.

The petition cited Tisby’s speech as a sign the school had lost its way, but school leaders claimed it was Tisby who had changed course. “The Jemar Tisby that we thought we invited in 2019 is not the Jemar Tisby that we heard in 2020 or that we now read about,” they told a board committee.

Tisby traces white evangelicals’ suspicions of their Black counterparts to the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, that followed the shooting death of Michael Brown. The protests, which brought the Black Lives Matter movement to national attention, drove a wedge between Black and white Christians, he wrote in a 2019 Washington Post op-ed.The split gained momentum in 2018 with a gathering in Memphis, Tennessee, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King Jr. Sponsored by the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention and the Gospel Coalition, a prominent Reformed evangelical group, the event featured a host of prominent leaders, including Piper, Texas megachurch pastor Matt Chandler, Baptist pastor Charlie Dates, legendary Black pastor and community organizer John Perkins and Russell Moore, then president of ERLC.

These preachers urged attendees to address the scourge of racism that stained the life of the church. Moore told attendees that enduring racism was leading younger Christians to question their faith.

“Why is it the case that we have, in church after church after church, young evangelical Christians who are having a crisis of faith?” said Moore, who has since left the SBC and is editor-in-chief of Christianity Today. “It is because they are wondering if we really believe what we preach and teach and sing all the time?”

That same week, an association of Southern Baptists in Georgia kicked a church out for racist actions against another SBC church. The Georgia Baptist Convention followed suit, as did the national Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting.

But in April of 2018, Tom Ascol, a conservative Southern Baptist pastor from Florida, criticized Thabiti Anyabwile, a well-known pastor in Washington, D.C., for writing about the sin of racism. Ascol, who would later run for SBC president largely on his opposition to CRT, produced a documentary about what he called liberal drift in the denomination.

The pushback had begun. By that fall, a group of conservative pastors, many of them Calvinists, signed “The Statement on Social Justice & the Gospel,” which responded to “questionable sociological, psychological, and political theories presently permeating our culture and making inroads into Christ’s church.”

In 2019, a resolution passed by the Southern Baptist Convention called CRT a “tool” to understand society and led to calls for the convention to denounce the resolution.

Those Southern Baptist debates over CRT long preceded debates in the general public. Ryan Burge, a political scientist, noted that Google searches for the term CRT were nearly nonexistent when Baptists started debating it. Only later did the debate spill out into the mainstream to be used by politicians, including Donald Trump, to rally supporters. It has since been equated with Marxism and other ideas anathema to conservatives.

Lerone Martin, associate professor of religious studies and director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, said that evangelicals have long found it easier to label Black leaders as leftists or Marxists rather than to deal with the reality of racism.

“That way, anything they dislike or oppose can be dismissed wholesale,” he said.

Tisby said he’s not an apologist for CRT or any ideology. He reads the Bible and history and tries to tell the truth, he said in an interview. That is his job as a Christian and as a historian. And he doesn’t think he’s all that special.

“I don’t think there’s anything in particular about my approach that is novel or different than what a lot of people have said for a long time.”