My high school English teacher provided us with some practical advice for reading complicated works of fiction well: keep a piece of paper nearby and write down the characters as they appear. Then add new information as you learn it. That way you can track all the players in the story and the associations between them.

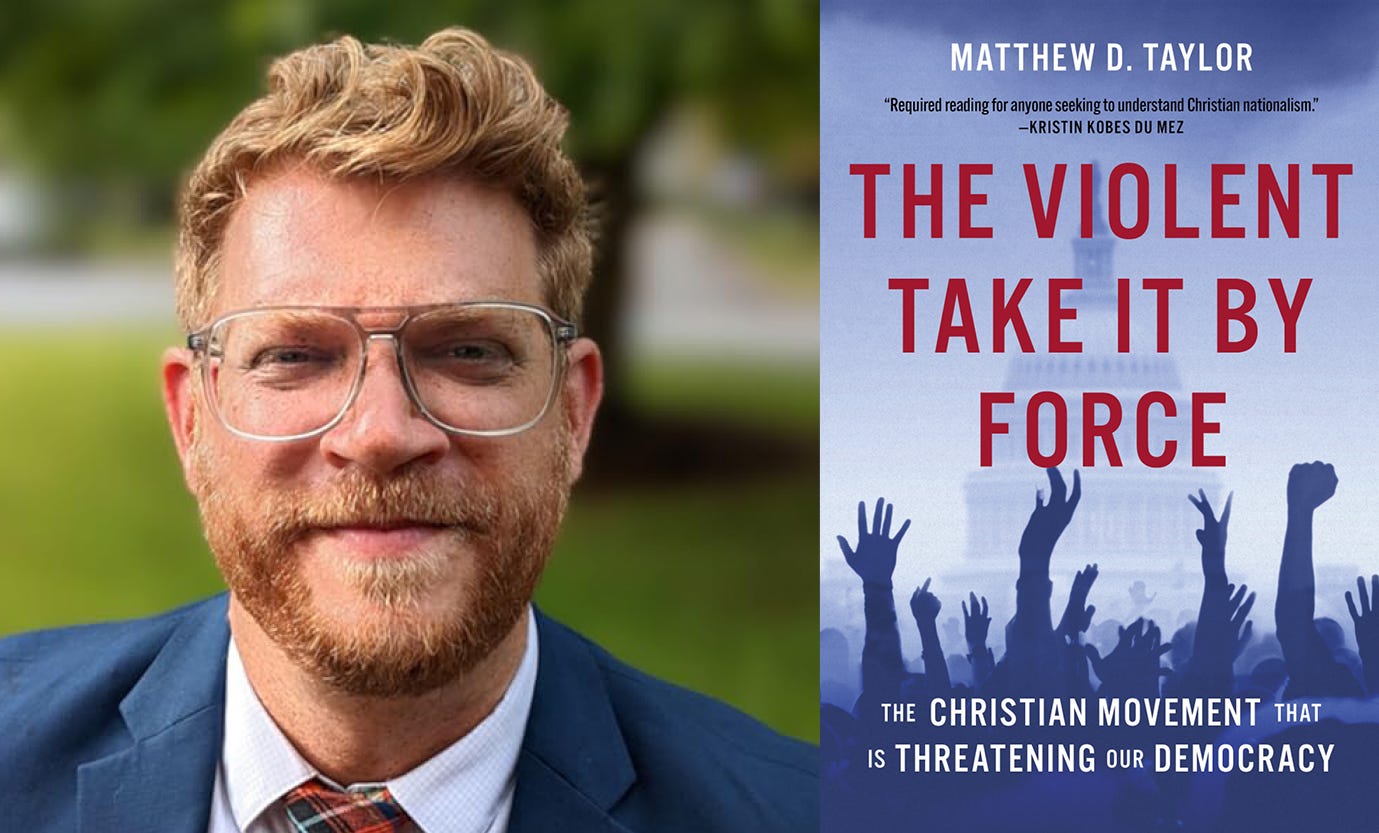

While that wisdom was meant to apply to imaginary stories, I found it quite useful in reading Matthew Taylor’s The Violent Take It by Force: The Christian Movement That Is Threatening Our Democracy. It’s a book with a long and wild list of complicated and interconnected characters. And it’s a story that would be unbelievable as a work of fiction, but is quite scary in the real-world impact that an array of seemingly eccentric and fringe faith leaders have had on both church and society.

The role that Christian symbols and rhetoric played in animating the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, has been well documented. Less understood is how our society arrived at a place where religion could be used to justify the attempted overthrow of a free and fair election. Taylor convincingly argues that it was a natural outgrowth of a charismatic movement known as the New Apostolic Reformation, whose leaders and ideas have migrated from the fringes to the center of American evangelicalism.

While the NAR is decentralized and diverse, Taylor outlines three core ideas that define the movement. The first is the belief that God has anointed apostles and prophets to revitalize the church today. These leaders operate within loosely connected networks that are outside traditional denominational authority and accountability structures. The result is a sensational form of Christianity driven by egos, eccentricities, and religious entrepreneurship.

The second element is the waging of spiritual warfare. Reality extends beyond natural experience to include battles between divine and demonic forces, with both humans and supernatural figures participating in a clash of eternal significance. Thus, people (like politicians) and events (like elections) are interpreted as being much more than the product of human reason and action. They are instruments in a cosmic struggle.

The third part is a theology that emphasizes how Christians should be in control of human civilization. Flying under various labels like “dominion theology” or the “seven mountain mandate,” the fundamental conviction is that power within a variety of cultural realms properly belongs to Christians for the sake of realizing God’s purposes.

Connecting these three ideas leads to the place where self-described prophets are broadcasting prayers on social media meant to alter the spiritual battlefield as mobs storm the Capitol. All in the hopes of reinstalling Donald Trump as president because they perceive him to be anointed by God as a Cyrus-like figure to redeem and restore America to its divine purpose.

Supporters of Donald Trump supporters kneel in prayer the day after the 2020 election during a rally outside the Maricopa County Recorders Office in Phoenix, Arizona, on Nov. 4, 2020. (Matt York/Associated Press)

The Violent Take It By Force provides both the history of how this movement emerged and an analysis of its growing influence within Republican and evangelical circles. The reader is introduced to a cast of characters, like C. Peter Wagner, Cindy Jacobs, Lance Wallnau, Sean Feucht, and Paula White-Cain. He shares their stories, explains their connections, and unpacks their beliefs and practices. Those who arrive at the book’s last page will feel like they’ve discovered a whole new world, which they are grateful to better understand but wish had remained far more marginal to American Christianity.

Along the way, Taylor helpfully complicates some superficial understandings of the movement he describes. For example, he notes how the independent charismatics that have advanced the ideas of the New Apostolic Reformation have featured more female and non-white leaders than other strands of U.S. evangelicalism. That fact underlies the degree to which their rise to power has really been a guerrilla movement within political and religious churches often dominated by White men. He also highlights how some mainstream institutions, such as Fuller Theological Seminary, helped advance the cause through the credentialing of leaders and the legitimizing of its ideas.

While there are plenty of moments in the book that will shock readers, a major takeaway is how many leaders and adherents to the New Apostolic Reformation’s principles truly believe in the beliefs they espouse and the goals for which they strive. Decrying them as dangerous and ridiculous without seriously interrogating what they’ve already accomplished — and still seek to achieve — ignores the influence this movement has already acquired. While Taylor’s stance is ultimately quite critical, he is clear-eyed enough about the danger to have invested the necessary time to comprehensively explain it to the rest of us. Now that the alarm bell has been run by him and others, the rest of us will determine whether the response is adequate to the threat.

“The NAR leaders and their hyper-politicized Independent Charismatic celebrity colleagues have cornered the market on supernaturally steered Christian rage,” he writes at the book’s end. “It behooves us, in an era of charismatic revival fury, to ponder what will happen if the NAR’s self-fulling prophecy actually unfolds. What will become of our pluralistic democracy if their Christian supremacist revival and reformation come to pass?”

You can hear more about the peril Taylor believes the NAR presents to church and state by listening to his recent interview on Dangerous Dogma. He’s also agreed to provide a signed copy of The Violent Take It By Force to one lucky paid subscriber to A Public Witness, so upgrade your subscription today to support our award-winning writing and make sure you’re eligible for that drawing.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood