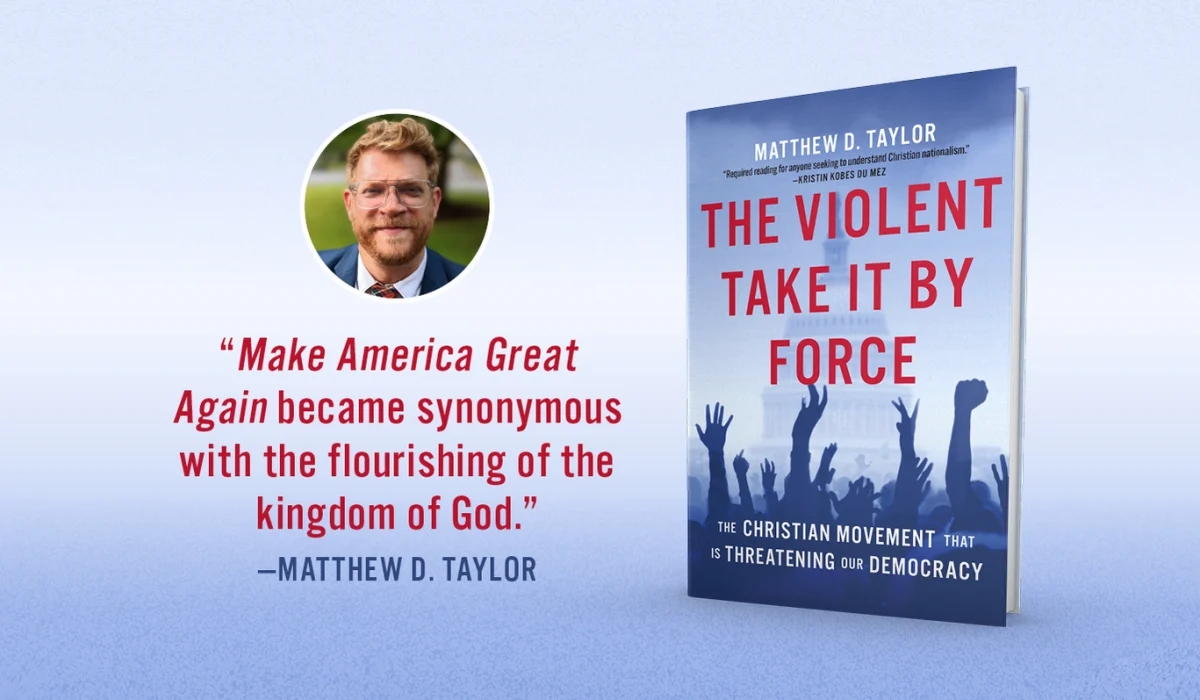

THE VIOLENT TAKE IT BY FORCE: The Christian Movement that Is Threatening Our Democracy. By Matthew D. Taylor. Minneapolis, MN: Broadleaf Books, 2024. 292 pages.

Christian Nationalism is a major topic of concern. Christian Nationalism comes in a variety of forms, some of which may be benign and others dangerous. The forms that become dangerous are the ones that threaten democracy by seeking power (dominion) over the nation. One name that has been given to this dangerous form of Christian Nationalism is dominionism, which also comes in different forms. However, at the heart of dominionism is Christian supremacy. That supremacy can include control of the government, education, culture, the media, and more. As such, it violates the whole premise of a democracy, even a representative one like we find in the United States.

Robert D. Cornwall

Matthew D. Taylor’s The Violent Take It by Force addresses this threat to our democracy that has emerged out of Independent Charismatic Christianity. The most prominent version of this movement within Christianity is known as the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR). Independent Charismatic Christianity largely flies under the radar, though it is present in many major mega-churches. It is a fast-growing religious movement across the globe. While it is built on the foundation of charismatic theology, it situates itself outside denominations, including Pentecostal denominations, and the various ministries are often connected through amorphous networks. There are numerous figures related to the movement, most of whom remain obscure and largely unknown, except in their networks. Nevertheless, they have had a significant influence both on the spread of a specific form of Christianity and the political and cultural life of the United States and elsewhere. The majority of these figures have aligned themselves politically with Donald Trump, believing he has been anointed by God, whether he’s a Christian or not, to usher in a new apostolic era.

Matthew Taylor, the author of The Violent Take It by Force, is a religious studies scholar and expert on independent charismatic Christianity as well as Christian Nationalism. He holds a PhD in Christian-Muslim Relations from Georgetown University and an MA from my alma mater, Fuller Theological Seminary (we attended in different eras). He currently serves as a senior scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian, and Jewish Studies in Baltimore.

The focus of Taylor’s book is on the political dimensions of this Independent charismatic movement. More specifically he focuses on the Apostolic and Prophetic Movement, especially the form known as the New Apostolic Reformation. Taylor distinguishes here between traditional denominational Pentecostalism and the independent charismatic movement. That is because this latter movement has few if any boundaries or overarching institutions. It is the realm of megachurches, televangelists, prophecy conferences, healing revivals, and the prosperity gospel. The movements under consideration began to emerge in the 1970s and 1980s as some within the independent charismatic world discovered the apostolic and prophetic dimensions of the early church and sought to restore them. More specifically, Taylor writes that this book “tells the story of how a cohort of respected NAR leaders embraced the candidacy of Donald Trump early on in the 2016 election cycle. By constructing creative theologies and biblical rationales for supporting a debauched real-estate mogul, they prodded and harnessed the latent power of a previously politically disjointed Independent Charismatic world” (p. 8). A central figure in this story is a former mission and church growth professor at Fuller Seminary, the late C. Peter Wagner. More about that later in the review.

The title of the book refers to a verse from Matthew 11, where Jesus spoke of the kingdom of heaven suffering violence and “the violent take it by force.” While Jesus likely meant the church would suffer persecution, Wagner and others in his movement interpreted the passage in a very unique way such that it gave support to their vision of spiritual warfare. While they envisioned spiritual warfare involving “spiritual violence,” their emphasis on spiritual violence may have spurred on physical violence, especially on January 6.

Taylor begins his story not with Peter Wagner and the NAR, but with Paula White, the prosperity-preaching televangelist who became Donald Trump’s spiritual advisor. While not directly involved with the NAR, she served as a mediator between Trump and leading Independent Charismatic Apostles and Prophets, many of whom were connected to Peter Wagner. Trump was attracted to White’s prosperity teaching, which led to her gaining entrance to Trump World. Since White was the mediator of the relationship between the Independent Charismatic World and the NAR, Taylor tells us something of White’s story, including her ministry as a woman preacher in a patriarchal world, along with her eventual entrance into Trump’s world and connections with his White House staff. Thus, the first chapter, “A Televangelist in the White House,” introduces us to both Paula White and the Independent Charismatic movement. This prepares the way for the coming together of the NAR and Donald Trump. That connection is one of the reasons why Trump has been able to attract such a loyal following among white evangelicals.

In Chapter 2, Taylor speaks of “The Genesis and the Genius of the New Apostolic Reformation.” In doing this, he first introduces us to C. Peter Wagner, one of the key figures in this new movement. Wagner grew up in New York City, but he studied agriculture in college because he developed a love of farming while visiting his grandmother and her small farming community. Later he met Doris Mueller, who in turn introduced Peter to evangelical Christianity. Together they chose to become missionaries, ending up in Bolivia. Along the way, Peter earned a master’s degree at Fuller Seminary, where Taylor and I also studied. He would later earn a PhD at the University of Southern California in sociology. This in turn led to a faculty position in the School of World Mission at Fuller. While the Wagners started as cessationists (the belief that the age of spiritual gifts ended with the last of the apostles), they eventually encountered Pentecostals and were drawn in. One of the key influences in Wagner’s growing attraction to charismatic Christianity was John Wimber, a leader in the Vineyard movement. In the 1980s, Wagner and Wimber taught a class called “Signs, Wonders, and Church Growth” (MC510).

I was a student at Fuller during those years, and I remember hearing stories from fellow students, some of whom took the class. It gained such a following not only among students but the general public that the seminary administration began to limit access to enrolled students. Wagner would get caught up in this charismatic fervor, eventually moving beyond Wimber’s orbit after discovering spiritual warfare, apostolic and prophetic governance, and more. Having spent time within Pentecostalism I was aware of elements of this movement, but Taylor reveals so much more about the creation and building of the movement that Wagner called the New Apostolic Reformation. It would be a movement marked by strategic spiritual warfare, apostolic and prophetic governance (oligarchy), and efforts to transform society at large. Thus, a form of dominionism emerged. Wagner wasn’t necessarily the creative genius of the movement, but he was the organizational genius. He set up a network that centered on his relationships with others who were considered or considered themselves apostles and prophets. Eventually, he would come around, shortly before his death to embrace Donald Trump as a key to his movement’s ability to transform society.

In Chapter 3, titled “Generals of Spiritual Warfare,” Taylor introduces us to another central figure in this emerging movement. That person is Cindy Jacobs, a woman who sensed a prophetic calling as a child and developed a vision of spiritual warfare that she would eventually introduce to Peter Wagner. Jacobs became a key figure and partner with Wagner in the development of the different spheres that make up the NAR. In this chapter, we not only learn of Jacobs’ ministry but also Peter Wagner’s departure from Fuller and move to Colorado Springs, which became a center for the NAR. We also learn how Jacobs’s vision of spiritual warfare played a role in energizing a certain element of evangelicalism to support Trump. The chapter also introduces us to another key figure in the apostolic movement, who remains a prominent figure in the Trump orbit, Lance Wallnau (J.D. Vance recently spoke at one of Wallnau’s events). What we learn here is that Jacobs played a central role in cultivating a network of people who participated in strategic spiritual warfare.

Chapter 4 is titled “The Second Apostolic Age.” In this chapter, Taylor explores the growing idea that Christianity has entered a new apostolic age while introducing us to the network of apostles who are the leaders of this new apostolic age. Most of the figures introduced here have been connected to Peter Wagner. Among them is a Korean American pastor who studied at Fuller with Wagner and started a Church in Pasadena, California. His church, Harvest Rock Church, became the center of a huge global network of churches and ministries that look to Ché Ahn for leadership. It is in this chapter that we learn more about the form of governance present in these churches and ministries. The governance takes the form of a top-down oligarchy. This is the form of governance that the movement would like to see instituted in the United States as a replacement for democracy. Thus, we learn about Ché Ahn and his ministry, which serves as a model of what is found throughout the Apostolic and Prophetic Movement. Once again Taylor points out the political implications of the movement by focusing on Ché Ahn’s challenge to California’s pandemic restrictions, taking his fight to the Supreme Court. What see here is how one apostolic figure offers himself as a source of authority not only over Christians but the entire world, building on a network completely submitted to his authority.

As the movement expanded, new elements emerged, which Wagner integrated into his movement. Among the elements added to the movement was a particular political ideology known as the Seven Mountains Mandate (Chapter 5). Lance Wallnau, one of the Apostles connected to Wagner’s movement, is the one who developed this ideology. Once again Taylor introduces us to one of the key figures in this growing movement. While Wagner has passed away, Wallnau remains a prominent leader in the movement. For our purposes, the focus of the chapter is on this social/political effort that envisioned Christian supremacy over seven spheres of society. Once again, Wagner brought this idea into his movement and shared it with his networks. Wagner already had an attraction to dominion theology and Christian supremacy, but what Wallnau did was develop the framework for instituting this vision throughout the NAR. The idea here is that there are seven spheres/mountains that shape nations and control minds. The goal is for Christians to gain control of them. While Donald Trump wasn’t considered an evangelical Christian, Wallnau came up with the idea that Trump was Cyrus and that through Cyrus the Seven Mountain Mandate could be instituted in the United States, giving Christians the opportunity to take leadership of government, education, business, media, and culture. Taylor also points out that Wallnau played an important role leading up to January 6th, offering theoretical guidance for what happened that day.

Chapter 6 introduces another element to this movement. This element involves “Worship as a Weapon.” In this chapter, Taylor introduces us to Sean Feucht, a young worship leader connected with the NAR and other Apostolic networks. Feucht has used his worship leadership skills to challenge pandemic rules and spread the message of the Apostolic and Prophetic movement using worship as the platform. We also learn something of the network he is connected with in Redding California, the Bethel Church. I would have liked to know more about Bethel Church as I believe it has had a significant influence on the political structures of the city and county (Shasta County), but that wasn’t the purpose of the chapter. A central theme of Feucht’s message that has caught hold among evangelicals is that they are being persecuted and that they should resist and push back against this persecution, such as the restrictions placed on churches during the pandemic.

The next element present in the NAR and Apostolic and Prophetic movement is described in Chapter 7, which is titled “A Governmental War.” This chapter focuses on the 2020 election and the response to Trump’s loss, including the events of January 6. The central figure in this chapter is Dutch Sheets, an early adopter of the Apostolic and Prophetic idea. Sheets was, by Taylor’s account, living at the “nexus of all the dynamics we’ve looked at: modern prophecy, strategic-level spiritual warfare, apostolic governance of the church, the Seven Mountain Mandate, and the utilization of charismatic worship experiences for right-wing political ends” (p. 206). Sheets believes he has a unique calling to use prayer and spiritual warfare to influence US elections. He has held this belief since at least the 2000 election but has found an even larger audience in Trump World. He has helped create prayer networks across the country in support of Republican efforts. He also introduced a key symbol to the struggle. That symbol is a flag that goes back to the Revolution. It is the Appeal to Heaven flag. This flag is white with a pine tree in the center, above which is found the words “Appeal to Heaven.” That flag was prominent in the crowd that rioted on January 6th. It is Sheets who introduced it to the right-wing Christian political world, and it has become a symbol of Trump’s efforts to regain power. It has been flown over the houses of a Supreme Court Justice (Samuel Alito) and on the walls outside the offices of Republican leadership in Congress, including Speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, who has his connections with NAR figures, including Lance Wallnau.

This would be a fascinating story if it wasn’t also a rather frightening one. Because this is a religious movement that largely flies under the radar, the media pays little attention to the massive network that has emerged in recent decades and has developed considerable influence on political efforts across the country. While abortion is one of the central issues, it’s not the only one. Consider the pushback on greater freedom for the LGBTQ world. According to Taylor, this is also a Christian problem because it has taken root in the Christian world. While the leaders of the movement condemned the violence of January 6th, many of them were at the Capitol or nearby and participated in Trump’s rally by encouraging their followers to join the crowd. One of the key conclusions here is that Christian Nationalism takes different forms and some forms are dangerous, especially if they have designs on gaining Christian supremacy. Added to the concern is that Independent Charismatic Christian movements are growing faster across the globe than any other Christian movement. So, while the United States is becoming less Christian, these movements are taking up a greater share of the Christian world. That is troubling both for the nation and for the future of Christianity.

Matthew Taylor’s The Violent Take It by Force is a lengthy and well-documented book that covers a lot of bases. It is deeply rooted in research and scholarship. Taylor has read widely and interviewed key figures in the movement. Like me he has evangelical roots, so he knows the lay of the land. Like many of us, he is concerned about the future of the nation and Christianity. Therefore, this is an extremely important book. I’ve read several books on Christian Nationalism in recent months, but this is one of the most important because it gets to the root of the issues facing us. It’s not only a matter of Christian Nationalism, which in some forms is little more than an elevated version of civil religion, but an effort to achieve Christian supremacy at the cost of the democratic values that undergird the American system. Then there is the personal dimension to the story that is particularly unsettling. That dimension is the connection of Peter Wagner with Fuller Seminary. While he left the school on less than good terms, as one of my former professors lamented, Fuller will never be able to separate itself from Wagner and his legacy. That is unfortunate. As I write this review, the 2024 election is only a matter of days in the future. Donald Trump has a good chance of winning, and if he does, his NAR backers will want a seat at the table. So, it behooves us to familiarize ourselves with this movement that is largely unknown and not well understood. Matthew Taylor has done us a great service in writing this book.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.