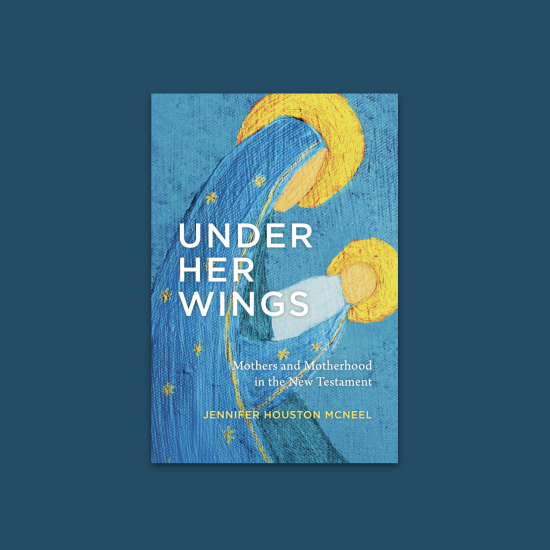

PILGRIM: A THEOLOGICAL MEMOIR. By Tony Campolo with Steve Rabey. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2025. 254 pages.

Tony Campolo is one of the best-known evangelical figures of the last half-century. While I’ve known about him and heard friends celebrate him for decades, I’ve never heard him speak or read any of his books, at least that I can remember. Perhaps that’s because my youth ministry days were brief, and I didn’t attend the conferences where he frequented. Nonetheless, he was a major figure in Christian circles who influenced many, both in the evangelical world and beyond. While he always claimed to be an evangelical, he lived on the left wing of evangelicalism. I offer this preface to my review of Campolo’s posthumously published theological memoir that carries the title of Pilgrim. As one will discover in reading his memoir which was published shortly after his recent death (Campolo passed away on November 19, 2024 at the age of 89), this is an apt title for his memoir.

Robert D. Cornwall

It is important to note that Campolo’s day job was a professorship in sociology at Eastern University in Pennsylvania. This American Baptist-affiliated university not only served as Campolo’s place of work but also his alma mater. Thus, his entire adult life, whether as a student or professor, was centered in that space. While he centered his professional life at Eastern University, he spent a lot of his life on the road, speaking to churches and conventions large and small. He focused much of his attention on youth and young adults, especially college students, which explains why my path did not intersect with his. While I didn’t interact with Campolo the speaker or writer during his lifetime, I acknowledge that he may have influenced my journey in ways I don’t recognize. Therefore, while this might be the first book of his that I will have read, I found it intriguing.

Campolo wrote Pilgrim late in life. Having suffered a stroke several years earlier he coauthored the book with Steve Rabey, who interviewed him and then provided Campolo with a written text. Campolo speaks of this book as a theological memoir. This is a good description of a book that speaks to Campolo’s life of faith and the theology that developed over time. He divides the book into five parts. Part 1 is titled “When I Was a Child.” In the seven chapters in this section, he shares the story of his youth, especially his coming of age in fundamentalist Baptist circles. He had devout parents who made sure he attended church, but he found another spiritual home in a fundamentalist bible study group called the Bible Buzzards (the name reflected their desire to devour the Bible). Nevertheless, the extroverted Campolo made lots of friends growing up, some of whom were Jewish, which led to questions about their salvation.

Those questions helped open his heart and mind to a broader vision of the Christian faith. Those relationships were coupled with a desire to be an astronomer. This embrace of science also ran counter to his fundamentalist views, because his fundamentalist friends and teachers believed that science was the enemy of the faith. His lack of math skills may have ended that dream but not his openness to science. Finally, there was the moment when the church he grew up in rejected the membership of an African American woman, which led to a crisis of faith. While still a fundamentalist at that point, he had begun to head down a road that would take him out of fundamentalism toward a much more open evangelicalism.

Part 2 is titled “One Who Correctly Handles the Word of Truth.” The five chapters in this section focus on the years Campolo spent in college, seminary, and ministry in the church. Here, we read how he sought to discover his calling, believing that he should either be a minister or a missionary. He would spend time as a pastor of several churches, Presbyterian and Baptist. These were the years he married Peggy, his lifelong partner with whom he at times had major disagreements. For example, she was far ahead of him on LGBTQ inclusion. During this period of his life, he once again encountered the racism that often existed in the churches. As with the church of his youth, one of the churches he served also rejected membership applications, this time from an African American couple. As was true of the pastor of the church of his youth, the church’s decision to reject the membership of the couple led him to resign.

The decision to leave the pastorate led to a moment of transition for Campolo. That time of transition is described in Part Three, which he titled “Hunger and Thirst for Righteousness.” It was at this point that Campolo began to pursue a new career pathway teaching sociology at Eastern College. He began his studies of sociology as a seminarian by taking sociology classes at the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University, both of which were near the seminary. He would eventually earn his PhD in sociology at Temple University. Besides teaching at Eastern, he spent several years teaching sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. During this time, he began to discern changes in his beliefs about war and peace, sexuality, and abortion. This was also the point in his life that he began his speaking ministry.

Part Four is titled “Public Theologian.” It is in this section that Campolo shares the story of his run for Congress in 1976 as a Democrat in what was hailed as the year of the Evangelical (Jimmy Carter was elected President that year). Although he lost the election, he learned a lot about the political world. His attempt at a political career also opened up new venues as a speaker. Even as he expanded his speaking ministry, he continued to develop his theology, though always on the run. Among the issues he wrestled with was capitalism, which led to accusations of heresy. He even faced a heresy trial at which he was acquitted. The decision that emerged was that while he might be a radical evangelical he was still orthodox in his theology. This is also the era in which he served as Bill Clinton’s spiritual advisor. This included his involvement in the aftermath of Clinton’s “affair.” We also learn here about the painful disclosure on the part of his son Bart, who had created his own ministry, that he was no longer a believer. This proved to be a difficult moment for Campolo because it caused him to struggle with his own Christian identity. While he would come to terms with his son’s decision, it forced him to wrestle with his own convictions. There is also a chapter in this section on his role in the founding of the Red Letter Christians movement, which was led by several of his former students including Shane Claiborne.

Finally, we come to Part Five, which is titled “The End of the Road.” Campolo writes that his identity was wrapped up in his teaching, writing, and, perhaps most of all, his speaking career. He had grown used to regularly speaking to large crowds, but then a stroke hit. The stroke brought his world to an end. While he could still speak, he could no longer travel. This was a difficult time, as anyone who has lived an active life can imagine. Yet, as he shares in the final chapter, “Sundays at Beaumont,” he found a new ministry because of his new reality. That new ministry involved leading worship and preaching/teaching a group of seniors at the nursing home where he lived during his final years. Like everyone else in the room, he was wheeled in. Yet, he discovered a new audience and a new ministry.

I expect readers will have different experiences with the book. My friends who attended his lectures and speeches, especially at Youth Specialities conventions, and read his books, will gain a new perspective on the public Campolo. Others, like me, who may have known about him and maybe have even read an article in a magazine such as Christianity Today, will gain a different sense of Campolo’s life. Ultimately, this is the story of a man who influenced thousands but who had his own struggles with his faith. This might prove encouraging to many who struggle with doubt and changing understandings of their faith experience. As I read, Pilgrim: A Theological Memoir, I found it interesting that he saw himself in many ways as an evangelist. He viewed his speaking events as an opportunity to invite people to come to Jesus. He might do so more subtly than Billy Graham, but that was part of his agenda as a speaker and writer. Although Tony Campolo never left evangelicalism, at least in his own heart and mind, it’s clear that the evolution of his faith, theology, and view of the world meant that his vision of evangelicalism was very different from what exists today.

While Pilgrim was published shortly after his death, he expressed his readiness to move on to the next chapter of his life. The final paragraph reads as such: “My earthly pilgrimage has been an amazing journey, and when my life ends, I will be ready to abandon this worn-out body and overtaxed mind and rest in the presence of God for all eternity (p. 246).” Although my experiences with Tony Campolo were few, it is clear that he understood that his own evangelical faith in Jesus required that he keep an open heart and mind so that he might continue to grow in faith, knowledge, and love of God and neighbor.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found here.