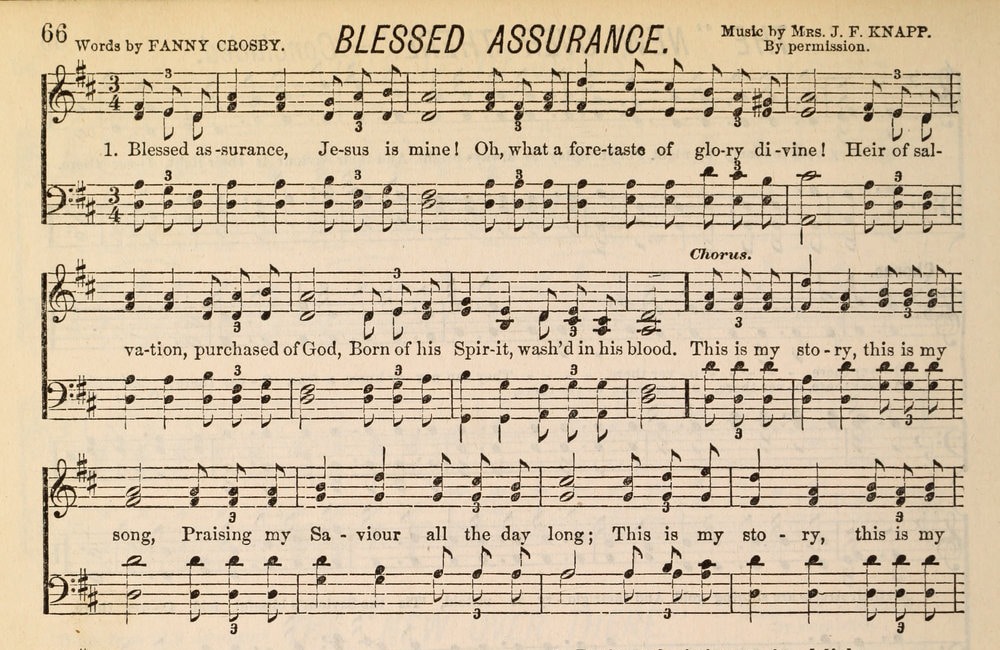

Remembering Fanny Crosby, Queen of Gospel Song Writers

All of you old-timers like me who grew up in Baptist, Methodist, or other “evangelical” churches know the name Fanny Crosby, the blind woman who wrote more gospel songs/hymns than anyone else in history. She was born 200 years ago this month.