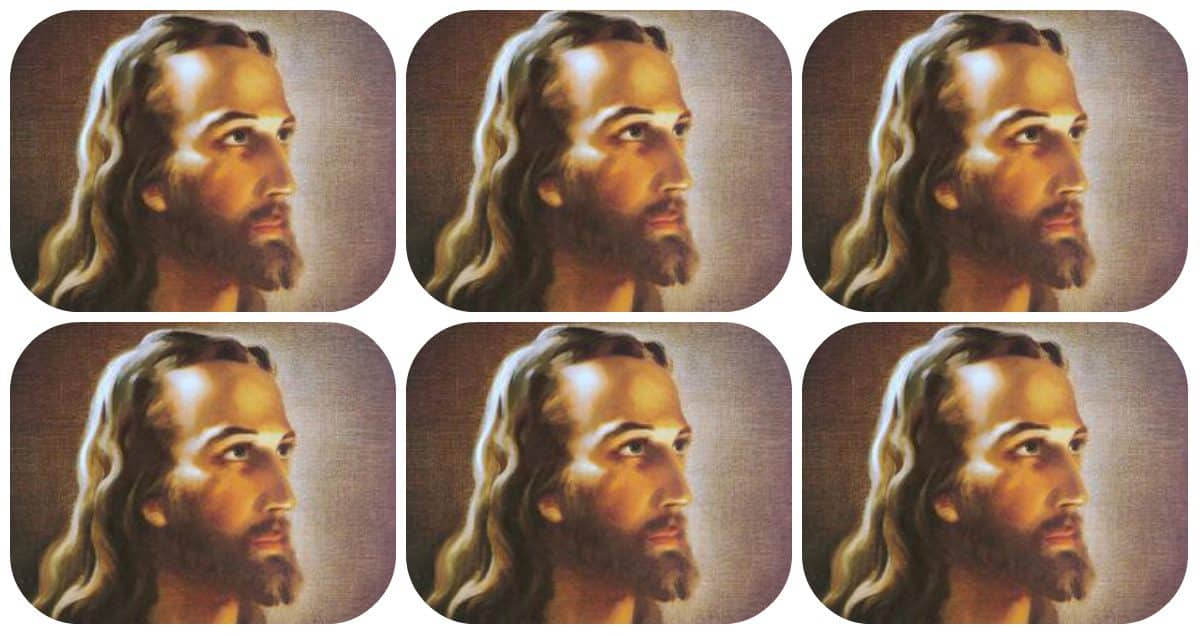

Warner Sallman painted Jesus in oil after people raved about his black and white sketch. It has been reproduced millions of times. Image by Warner Sallman/collage by The Conversation

(The Conversation) — April 30 was the 127th birthday of an artist whose name you probably don’t know, but his work may be the most widely distributed of the 20th century. Despite never leaving Chicago, Warner Sallman influenced how many Christians the world over, for better or worse, picture Jesus.

Anderson University in Indiana holds Sallman’s collected works. Their collection notes explain how images like Sallman’s may be objects of beauty, historical artefacts, mementos, articles of piety or propaganda in the service of an ideology. The truth is that religious images can serve all these purposes.

They can also sell products.

Reproductions of Sallman’s warm, sympathetic, Nordic and very much non-historical “Head of Christ” hang in churches of every sort, and in confessional schools and hospitals on every continent. In his book, “Icons of American Protestantism” David Morgan of Valparaiso University in Indiana tells how millions of pocket-sized “Heads of Christ” cards were handed out by the YMCA and Salvation Army during the Second World War and carried to Europe and Asia by U.S. soldiers.

Sallman was a freelance illustrator and a devout member of the Swedish Evangelical Covenant Church. One of Sallman’s 1924 black and white sketches for the Covenant Companion magazine received such praise he painted it in oils, creating, in 1940, the “Christ” that would go on to sell 500 million copies.

That number multiplied exponentially when reproductions started appearing on clocks, lamps, buttons, laminated Bible verses, music boxes and night-lights. When the “Head of Christ” became a hit, Sallman followed up with “Christ at Heart’s Door,” and “Christ our Pilot.”

Mass produced kitsch

Already in the 1930s, there was a long tradition of “Caucasian Jesus portraits,” just as there had been, since the mid-18th century, literary “lives of Jesus.” These “lives” tended to portray Christ as representing the best of European (male) culture.

Visual images of Jesus painted by Europeans reflected those who painted him; only on rare occasions, such as when Jesus was portrayed as a red-headed youth, did historians object. From the time of the ancient Romans, Christians have always “contextualized” Jesus in their own image.

What changed in the 20th century with Sallman was that Jesus images met American advertising and mass production. Prayer met plastic.

Is Sallman’s portrait a kitsch Jesus? Certainly it wasn’t for the artist. Despite his beard, the “Head of Christ” is anything but hipster irony. The image is a bit dated now. But for many there is nothing jarring in the high forehead, broad shoulders and long nose. For them this is, simply, what Jesus looks like.

Masculine portrayal?

Apparently, Sallman was attempting to create a more masculine Jesus than earlier portrayals. Ironically, many now find his Jesus effeminate — demonstrating the extent to which definitions of “masculine” are cultural and fluid rather than biological. In Jesus’ own day, and as a Jew in the Roman Empire, masculinity was as contested then as it is now.

Of course, the historical Jesus was neither Nordic, nor American. The visual mono-culture of the United States, relatively new in Sallman’s time, has since given way to the fractured image-production of the 21st century — the end of a taken-for-granted singular way of seeing.

The way Christians picture Jesus, whether in two- or three-dimensional art, says much about the way they perceive God. Devout Christian artists portray Jesus as Nigerian, South Asian, Korean or Indigenous. Jesus has been sculpted by Canadian Timothy Schmalz as a homeless street person and portrayed by other artists as a crucified woman or even as faceless, a mirror to our angst.

Kitsch is in the eye of the beholder, or better, the attitude of the consumer. There are bobble-head Jesuses and inflatable Jesus pillows.

The staying power of Sallman’s 1940 Nordic “Head of Christ” tells us nothing about the first-century Mediterranean Jewish teacher. But the appeal of Sallman’s painting reveals much about both globalized Americana and popular religious sentiment — the kind of surprising piety that can surface when a “Jesus image” appears at a Tim Hortons in Cape Breton.

Kitsch has always been slippery to define, and religious kitsch especially so. Were he still alive, Sallman would probably insist his paintings were just an aid to faith. They were certainly anti-elitist.

However honest Sallman’s own feelings, it is difficult to distinguish the distribution of his images from the wider ideological program of mid-20th century America. On this anniversary, it’s important to remember how powerfully formative feelings can still attach to a well-marketed image.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.