NOTE: This piece was originally published at our newsletter A Public Witness.

I got into an argument with a state senator on Tuesday (Feb. 17). I thought something like that might occur since I went to testify against a Christian Nationalist bill in a Missouri legislative committee chaired by a Christian Nationalist politician I’ve tangled with before. But while I expected we would disagree philosophically, I didn’t foresee we would instead just be arguing about whether a historical claim was true or not (or that I would respond by singing a line from Hamilton).

Whether or not the delegates at the Constitutional Convention prayed after Benjamin Franklin said they should is not a matter of opinion but fact. But the head of the Senate Education Committee thinks we should force public schools to teach that the prayer occurred even though it did not.

But before we get to the prayer that never was, let’s back up.

Last fall, some Republican lawmakers in Ohio introduced a bill to encourage public schools to teach “the positive impacts of religion on American history.” The proposal includes numerous such examples for teachers to highlight, some of which could be used to portray the United States as a “Christian” nation. Introduced shortly after the assassination of MAGA political activist Charlie Kirk, they named their legislation the “Charlie Kirk American Heritage Act” even though it doesn’t mention Kirk beyond that title. While the bill passed the Ohio House on a party-line vote, it’s still pending in the Senate.

Over in Missouri, state Sen. Nick Schroer, a rightwing politician with a record of pushing Christian Nationalism, liked the bill so much he mostly copied and pasted it for the Show-Me State to consider. He acknowledged that origin in Tuesday’s hearing, but he didn’t name his after Kirk (and I’m not sure why Schroer is trying to cancel Kirk). There’s also a bigger difference he didn’t mention. Rather than merely encouraging the teaching of the “positive impacts of religion,” his legislation says public schools “shall” do so and then also says the various examples “shall” be included instead of “may” be taught.

The Missouri Capitol in Jefferson City. (K. Trimble/Creative Commons)

Both the Ohio bill and the Missouri copycat one include historical errors listed as “examples” of the “positive” impact of religion. That makes the Missouri bill worse since it would mandate that those Christian Nationalist tall tales be taught as history. For instance, one required item to teach would be “the historic role of the black robe regiment.” Popularized by pseudo-historian David Barton, pundit Glenn Beck, and some Christian Nationalist pastors, the claim is that the “Black Robe Regiment” was a group of clergy supporting American independence during the Revolutionary War. The story they particularly like to tell is of Rev. Peter Muhlenberg, a Lutheran minister who later became a U.S. senator, giving a patriotic sermon to his congregation in 1776 and then pulling off his clerical robe to reveal a Revolutionary Army uniform and encouraging his congregants to enlist.

There’s a big problem with the Muhlenberg story and the claims of a so-called “Black Robe Regiment.” None of it happened. The tale about Muhlenberg’s robe-stripping sermon was first told 73 years after it supposedly occurred (and 42 years after his death). That is, it was made up by later generations. And the phrase “Black Robe Regiment” is an even more modern invention, perhaps arising from Barton misreading the historical records. Yet, this fake history is popular with Christian Nationalists today who like to imagine themselves as the new “Black Robe Regiment” while supporting the Jan. 6 insurrection and pushing for Donald Trump. Now, some lawmakers want public schools to teach the so-called “Black Robe Regiment” as a historical fact.

Schroer included more fake history in his arguments for his bill during Tuesday’s hearing. For instance, he declared that Congress “authorized the first printing of the Bible in America in the 1780s.” Once again, there’s a problem with that claim. It’s not true. While Christian Nationalists like Barton love to tell this fake story about a failed Bible project, the Congress of the Confederation did not actually authorize the printing of a Bible in 1781 despite being asked to by printer Robert Aitken.

Schroer isn’t just the sponsor of the bill; he’s also a member of the Senate Education Committee. And he’s using his power in public office to push multiple fake stories he wants taught as history in public schools. Sadly, he’s not alone. The chair of the committee, Sen. Rick Brattin, shares Schroer’s goal of pushing Christian Nationalism in public schools. And Brattin also joined Schroer in mixing up the facts about a prayer request from old Ben Franklin.

Poor Richard

Another one of the “historical accounts” proving the “positive impacts” of Christianity on U.S. history included in the Ohio and Missouri bills concerns a moment in 1787 as the nation’s founders tried to hammer out the U.S. Constitution: “Benjamin Franklin’s appeal for prayer at the constitutional convention.” It’s one of the issues that, like the “Black Robe Regiment,” I planned to address in my testimony. But even before I got the chance, the committee chair brought it up as he praised the proposed bill.

“I appreciate your bill and I think teaching real, proper, true history is paramount,” Brattin told the bill’s sponsor during the hearing. “It’s just actual, historical, factual information of the founding of the nation. The premise behind — I see Benjamin Franklin, who’s always thrown out there as a deist, but he basically saved the convention and brought everybody to a halt and brought them to prayer. And he prayed to — I mean, it’s not like invoking religion. It’s stating exactly what actually happened during the convention and the fact that he actually did do those things.”

Except it isn’t real, proper, true history. Franklin did not, in fact, actually do those things.

As I said a few minutes later during my testimony about the reference in the bill to Franklin’s prayer request: “What is left out of that is that Franklin’s appeal was overwhelmingly rejected by the delegates after Alexander Hamilton and others spoke against it. So, no, they did not actually stop and pray.”

We know this because it’s recorded in the minutes from the Constitutional Convention. That group convened in Philadelphia on May 25 (and would continue until September 17). More than a month into it, there were a lot of disagreements the delegates were struggling to work through. So on June 28, Franklin mentioned “the small progress” made so far and therefore suggested they turn to God for assistance.

“God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid?” Franklin said, borrowing from and then adding to Matthew 10:29. “I therefore beg leave to move — that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the clergy of this city be requested to officiate in that service.”

Roger Sherman, the second-oldest delegate after Franklin, seconded the motion for daily prayers at the convention. But then the minutes note that “Mr. Hamilton & several others expressed their apprehension,” arguing that the motion could spark new criticisms (perhaps since religion can do that) and could also be bad public relations by signaling to people that things are going so poorly they’re resorting to prayer as a kind of legislative Hail Mary.

Howard Chandler Christy’s 1940 painting, Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States. (Public Domain)

Amid the discussion, delegate Edmund Randolph offered an alternative motion — seconded by Franklin — that instead of starting daily prayers right away, they have someone preach a sermon on the Fourth of July and then start daily prayers at the convention after that. Ultimately, the measure had so little support, they just adjourned without even bothering to vote on it, thus killing the proposal. Franklin added as a note to his record of the proceedings: “The Convention, except three or four persons, thought prayers unnecessary.” James Madison later explained the opposition was largely because of “the differing religious convictions of the delegates” and local clergy, especially given the different worship style of Quakers (who greatly influenced religious life in Pennsylvania).

Despite that, many people today insist that the delegates did actually pray — and that the prayer is what saved the convention.

The myth appears to have started in 1815, nearly 30 years after the actual events were recorded in real time — and Madison, who was still alive, rejected the new version as “erroneous.”

Today, the apocryphal version is frequently claimed as a fact in politics. President Ronald Reagan invoked the story in 1986 with the new ending. He said he found it “funny” that it was a deist like Franklin “that uttered the statement in the Constitutional Convention that finally got them to open the meetings with prayer.” He gave this alternative history while trying to justify his push for government prayers in public schools. Scott Turner, a Southern Baptist pastor who now serves as secretary of Housing and Urban Development, invoked Franklin’s call for prayer last year during a meeting of the White House’s so-called “Religious Liberty Commission” as he announced the White House’s new “America Prays” initiative. Trump has also told the story, like using it to justify saying, “‘Merry Christmas’ again.” And Christian Nationalist peddlers of misinformation, like Barton, also like to push this fake story.

So while I’m not surprised to hear it told, it’s particularly troubling when lawmakers on a state education committee repeat it and demand that public schools teach this fake history. Brattin, the committee chair, was not pleased with my claim during the hearing that Franklin’s request was rejected. Here’s how that exchange went down after my prepared remarks, with Brattin apparently thinking not just that they prayed but that Franklin himself gave the prayer:

Brattin: But they did stop the convention because he did pray the prayer. Kaylor: No, that’s actually not true. Brattin: No, he did actually stop and pray the prayer. Kaylor: No, it’s not true. They did not pray. Alexander Hamilton — maybe you’ve heard of him — Alexander Hamilton. ... He argued against it.

It’s not clear from the transcript, but I delivered the second “Alexander Hamilton” in my impersonation of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s response in the hit musical to the question, “What’s your name, man?” In doing so, I proved why I perform in my church’s orchestra instead of the choir.

But Brattin was unmoved by my argument (or my singing).

Kaylor: They did not have a prayer at the Constitutional Convention after Franklin’s request. Brattin: So this was made up, that the fact that they wrote the prayer down of his actual words of what he uttered, did not occur? Kaylor: Franklin’s request was rejected.

At this point, he moved on. But I’m confident he still believes the fake story and wants to force it to be taught as fact.

Help sustain the journalism ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

History Has Its Eyes on You

Beyond the historical inaccuracies pushed in the hearing and in the legislation, there’s also a problem with the overall framing in the bill. Here’s how I explained it to lawmakers in my testimony:

It is important for public schools to teach the historical impact of religious individuals, groups, and ideas. However, this legislation starts off problematically by requiring schools to teach “the positive impacts of religion on American history” as opposed to the complete history of how religion has impacted the nation. I wish it was all good, but sadly it is not. And we must teach history as it was, not as we wish it was.

For instance, this bill mandates teaching how religious individuals like Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. pushed for civil rights in large part because they were motivated by their faith. And that is very good to teach. But our school children need a more holistic understanding. Because the Christian faith was also invoked by enslavers to justify slavery, by Confederate leaders to justify fighting so they could continue enslaving people, and by segregationists to defend discrimination and condemn MLK. By only teaching one side of that equation, we give people an inaccurate understanding of American history and of religion.

I could give some more examples of misleading teachings and outright historical fables. Instead of advocating for religion with this bill, we should find ways to teach the truly radical and important American contribution when it comes to religion — and that is religious liberty for all people, regardless of what they believe. And there are a few good examples of this in this bill, including item 11 about John Leland and item 12 about Roger Williams — both of whom were colonial Baptists. But that emphasis is oddly lost in item 10 that tries to make the Constitution a religious document instead of one that rejected the idea of establishing a religion. And other items, including the one about Franklin, undermine helping students learn about the foundational vision of true religious liberty for all.

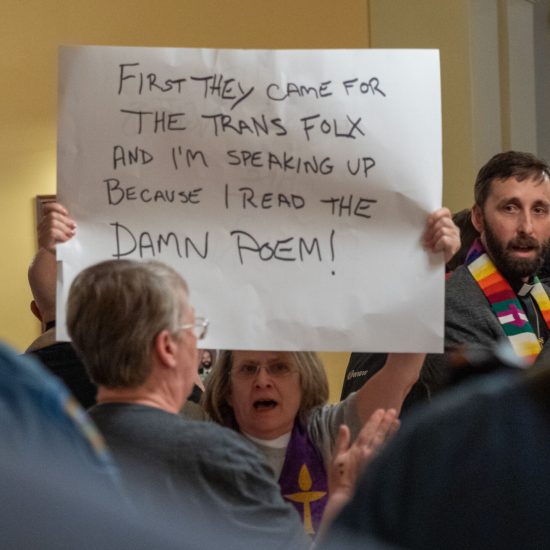

Ultimately, this legislation isn’t about teaching history; it’s about pushing Christianity. And especially in this year of semiquincentennial celebrations of the U.S.’s founding, we’re going to see fables pushed as “history” to justify Christian Nationalist policies. We’ll need to speak out against the myths. I’m not throwing away my shot.

What we really need is a recommitment to the foundational experiment of church-state separation. Ironically, it’s a lesson we can even learn from Franklin requesting prayer. Because the Constitutional Convention was not saved by prayer. Rather, they avoided sectarian entanglements and rejected the more common practice of praying at legislative bodies to instead work through the issues civically in order to craft a constitution that did not unite church and state. Now, that’s something worth celebrating and teaching!

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

By the way, you can hear my full testimony and my exchange with Sen. Brattin in this video: