(RNS) — Southern Baptist Convention President J.D. Greear said, “ Of course, Black lives matter.” Religious broadcasting veteran Pat Robertson stated, “It seems like now is the time to say, ‘I understand your pain. I want to comfort you.’” Houston megachurch pastor Joel Osteen declared, “We need to stand up against injustice and stand with our Black brothers and sisters.”

Many prominent white evangelicals have made statements about Black lives in the weeks since the May 25 death of George Floyd, but is this new focus among white conservatives — and white Christians in general — momentary or lasting? Researchers working at the crossroads of religion and race say it’s too soon to say. But highlights of a forthcoming study, which looks at racism, biblical interpretation, and church cultures, may indicate a long struggle ahead.

Michael Emerson, co-author of the 2000 book Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America, said 2019 findings indicate “zero evidence” of a closing of the long-standing gap between how white evangelicals and Black Christians view racial inequality. When asked if the country has historically been oppressive for racial minorities, 82% of white evangelicals do not agree, said Emerson, head of the sociology department at the University of Illinois at Chicago. In comparison, among practicing Christians, 75% of African Americans agree, along with more than 60% of Hispanics, while 60% of whites do not agree.

When respondents were asked whether systemic racism or individual prejudices were the bigger problem in the country today, two-thirds of African Americans pointed to systemic racism while the same proportion of whites blamed individual prejudices. Among evangelicals, 7 in 10 (72%) faulted individual prejudices, 12% said systemic racism, and the rest answered “I don’t know.”

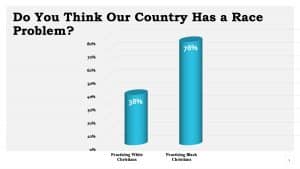

(Graphic courtesy of Race, Religion and Justice Project/Religion News Service)

Scholars of the Race, Religion, and Justice Project — a collaboration considered the largest ever of its kind — have also found that more than three-quarters of Black practicing Christians (78%) said the country has a race problem, compared with 38% of white practicing Christians.

The survey of 2,900 American adults, conducted in partnership with Christian research firm Barna Group, defined “practicing Christians” as people who identify as Christian, attend worship services at least monthly, and say faith is important to them. The overall findings had an estimated margin of error of plus or minus 2.2 percentage points.

Glenn Bracey, a principal investigator for the project, along with Emerson, said the race-related statements by religious leaders in recent weeks may not foreshadow a coming structural transformation.

“I have noted a lot of churches, including the Southern Baptists, coming out and saying that this is even up to the level of a gospel issue,” said Bracey, an assistant professor in Villanova University’s Department of Sociology and Criminology. “That said, there doesn’t seem to be much understanding around the country, and certainly not being led by the church, of the systemic changes that would need to take place in order to realize how Black lives matter.”

He said such changes would involve spending money to reduce segregation in housing, education, and employment.

“I haven’t seen any moves in that area,” said Bracey. “And our data suggest, I would say, that white evangelicals would have a long way to go before they were willing to see those.”

Glenn Bracey (left) and Michael Emerson present during Mosaix Global Network’s Multiethnic Church Conference on Nov. 6, 2019, in Keller, Texas. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

The project, whose additional results are expected in forthcoming publications, also examined some biblical interpretations by people who agree the Bible should be used to determine right from wrong. There was no difference among practicing Christians of various races and ethnicities when asked about Ephesians 4:29, which cautions against using “unwholesome words” and was interpreted in a survey question as “Therefore, it is bad to use curse words.”

But there was significant divergence on other passages that deal with treatment of minorities and foreigners, such as Acts 6:1-7, which a survey question summarized as a description of early Christians reacting to complaints of an ethnic minority group and empowering leaders of that group to address the problem.

Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with this interpretation: “Therefore, it is good to listen to the complaints of ethnic minority groups and empower leaders within those minority groups to correct injustice.” In the cases of three questions of this sort, the majority of people of color strongly agreed with the interpretation. Less than one-third of whites came to the same conclusion.

The scholars also gauged how willing respondents were to attend a church of a particular culture and one with a pastor of a particular race. Via computer, respondents were shown images of a Black or a white pastor with several randomly selected choices of music playing as they viewed the pictures, Emerson and Bracey said. Respondents of any race were generally willing to attend a white male pastor’s church. Black people were fine with attending a Black male pastor’s church as gospel music (“ I Do Worship ” by the New Life Community Choir featuring John P. Kee) played with his photo.

“But the other folks were only willing to go to his church, if he was playing Hillsong music,” Bracey said of the survey that featured a Black pastor during the playing of Hillsong’s “ Forever,” a worship song Emerson described as “classic contemporary white music.”

Emerson, who is white, said the findings demonstrate a white male advantage as churches make plans to expand.

“If you’re trying to build a church, start a church, grow a church, the sad message there is you want to hire a white pastor, a white male pastor,” he said. “If you’re African American, you’re going to have to do white culture, if you’re going to attract whites and Asians.”

Though the project’s findings preceded the events of recent weeks, Bracey said history may inform the outcomes from them.

“I don’t think protesting or activism is a waste of time by any stretch,” said Bracey, who is Black. “I’m glad that I live post-civil rights movement and not pre-civil rights movement as a Black man. But the end of Jim Crow was not the end of racism. And, these policy changes that we hope to see will not be the end of racism either.”