Charles Taylor published A Secular Age while I was in divinity school. Given the significance of the book and the attention it generated, the faculty decided to read and discuss it together. Because of the length and density of the volume, I recall one professor describing his approach to it: “I read ten pages before bed each night and try to remember what they said in the morning. If I can’t recall the argument well, I read them again.”

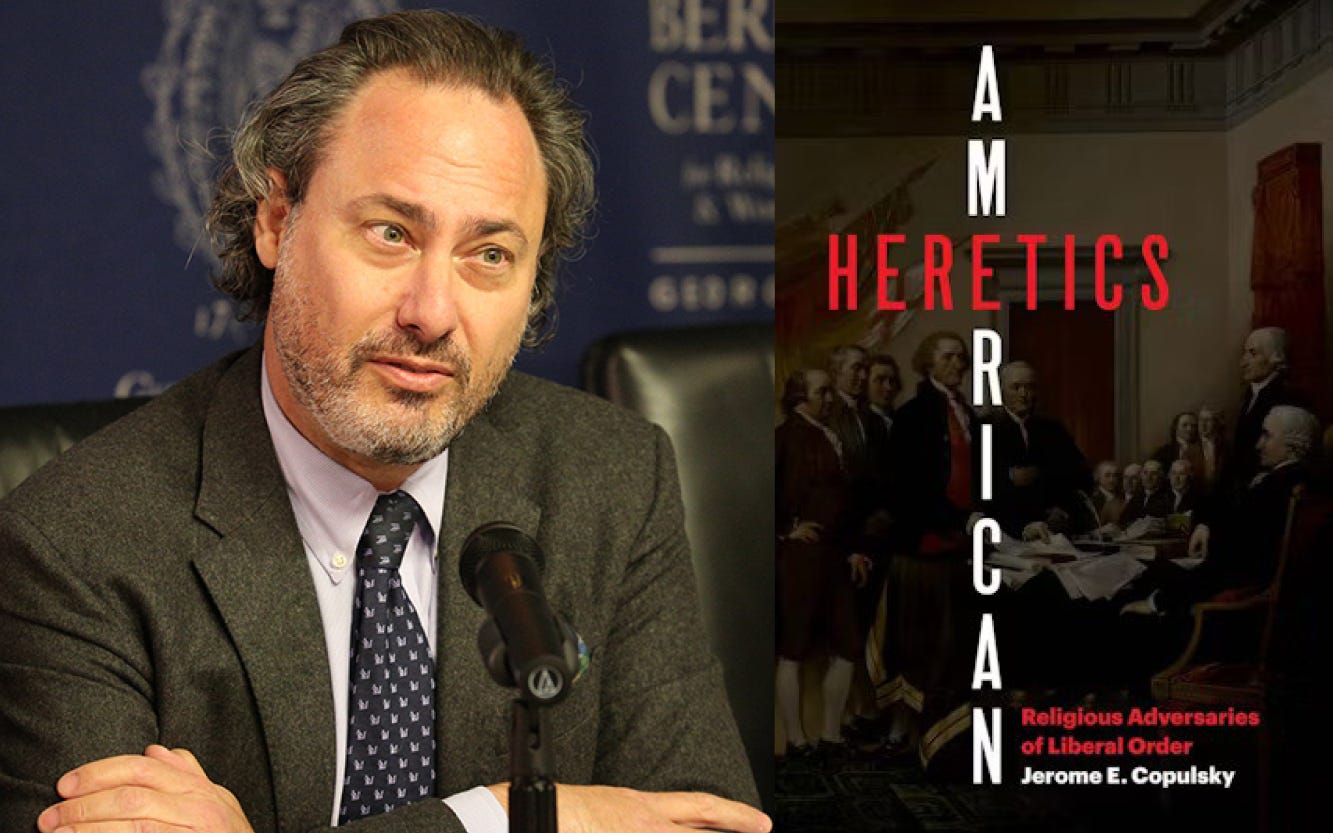

I took a similar approach to digesting Jerome Copulsky’s American Heretics: Religious Adversaries of Liberal Order. It’s neither as lengthy nor as complex as Taylor’s work, but it makes an important argument rooted in intellectual history: throughout the entire existence of the United States, there have been Christians opposed to the project of American democracy.

“Even though these traditions disagreed fundamentally on many theological matters, they all shared this idea that the founding was essentially infidel,” he explained to Brian Kaylor in a recent episode of our Dangerous Dogma podcast. “And that either the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution were therefore at odds with, or in tension with, revealed truth.”

To demonstrate the validity of this claim, Copulsky helps the reader hear voices within America’s past that are often ignored and to become aware of those in the present who seek to move from the margins to the mainstream. Those forgotten and dismissed perspectives are the arguments of Christian leaders who have sought to challenge core pillars of American democracy. For various reasons, they opposed the separation of church and state, the protection of religious liberty, and the fostering of religious pluralism that are inherent to this particular political project.

In this sense, they are challenging the accepted wisdom and agreed upon principles of their time. Thus, he brands them as heretics “as a way of registering the fundamentally religious nature of their dissents and highlighting the irony that they did so while claiming to be upholding Christian orthodoxy.”

Their apostasy takes on different forms. During the Revolutionary War era, the critics were Anglican clergy who rejected the idea that the ultimate power of government rested in the people below rather than God above, mediated through the monarchy and sacralized by the episcopacy. The failure to recognize the early nation as Christian in character was an affront to the Divine that promised to bring chaos and disorder to the fledgling state.

Fast forward to our contemporary moment where Copulsky highlights the thinking of post-liberals and national conservatives who talk of abandoning democratic commitments in order to realize a society that aligns with their religious “traditionalism.” As the political influence of Christian conservatives has waned, democratic institutions are no longer a viable means for achieving their goals. Instead, much more radical action is needed.

Consider the implications of a document, “National Conservatism: A Statement of Principles,” published by the Edmund Burke Foundation and signed by a notable number of thinkers who would qualify as heretics under Copulsky’s label. It states:

The Bible should be read as the first among the sources of a shared Western civilization in schools and universities, and as a rightful inheritance of believers and non-believers alike. Where a Christian majority exists, public life should be rooted in Christianity and its moral vision, which should be honored by the state and other institutions both public and private.

However those convictions might be put into practice, they are in direct conflict with constitutional prohibitions on religious establishment, protections of religious liberty, and the commitments to all enjoying equal status within the public sphere.

U.S. Capitol Police officers walk in front of a painting depicting the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence as they respond to the pro-Trump mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. (J. Scott Applewhite/Associated Press)

For those who are stringently orthodox when it comes to preserving and protecting American democracy, Copulsky’s book offers a valuable lesson that we seem to be learning anew in this political moment: liberal political values and institutions are more fragile than we care to realize. The freedom to live and believe within a society where all enjoy an equal say is vulnerable to populist demagogues who would use those very liberties to organize power to harm racial, cultural, and religious minorities. Left unchecked and unchallenged, such leaders use democratic means for undemocratic ends.

Yet, there’s a cautionary tale in these pages that present day democratic heretics would be wise to heed. Those motivated by the myth that America was founded as a Christian nation will find their assumptions exploded. It’s not that such an understanding once existed but has been lost. Rather, it is that such an idea was argued and advocated for from the beginning but discarded as both impractical and in conflict with American values. This book provides further evidence that the nostalgia inspiring Christian Nationalism is an ahistorical invention.

American Heretics is a tour de force that documents the religious illiberalism that has challenged democratic values from the very beginning. It belongs on the bookshelf of any student of the evolving relationship of religion and politics in the United States. We’ll be providing one lucky paid reader of A Public Witness with a signed copy of the book, so upgrade your subscription today to ensure you’re eligible for the drawing. And as you read it, say a prayer for our democracy.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood